Shira (100 page)

Let me state this in terms of the quest for knowledge that is a central issue in the novel. Herbst and his fellow cultivators of the grove of academe, equipped with their index cards and bibliographies and learned journals, sedulously pursue the most esoteric and distant objects of knowledge – the burial customs of ancient Byzantium, the alphabets of long-lost languages. The purported sphere of these objects of knowledge is history, but do these historical investigations, beyond their utility in advancing the careers of the investigators, tell us anything essential about the historical forces that are about to move the German nation to gun down, gas, and incinerate millions of men, women, and children? The European perpetrators of these horrors are, after all, at least in part products of the same academic culture as Herbst and his colleagues. The most troubling question a Jewish writer after 1945 could raise is variously intimated here, particularly in Herbst’s nightmares and hallucinations: Could there be a subterranean connection between forces at work, however repressed, within the civilized Jew and the planners and executors of mass murder who are, after all, men like you and me? At the beginning of the novel, Herbst is unable to write that big second book which will earn him his professorship because he has a writer’s block. As the effects of his exposure to Shira sink in, he is unable to write it because it has become pointless, such knowledge as could be realized through it felt to be irrelevant. Instead, Herbst hits on the desperate idea of writing a tragedy, for his experience with the radical ambiguity of eros in his involvement with Shira/Poetry leads him to sense that art, unlike historical inquiry, has the capacity to produce probing, painful self-knowledge, and is able to envisage history not as a sequence of documented events but as a terrible interplay of energies of love and death, health and ghastly sickness. Herbst, with his habits of academic timidity, his hesitant and unfocused character, may not ever be capable of creating such exacting art, but he is ineluctably drawn to the idea of it.

The underlying concern with the nature of art in

Shira

is reflected in its wealth of references – scrupulously avoided elsewhere in Agnon’s fiction – to European writers: Goethe, Nietzsche, Balzac, Rilke, Gottfried Keller, Stefan George, not to speak of the Greek tragedians and their German scholarly expositors whom Herbst reviews in his quixotic attempt to write a tragedy (ostensibly, a historical drama set in the Byzantine period but unconsciously a reflection of his own agonizing erotic dilemma with Shira). From one point of view, this is a novel about the impossibility of tragedy in the modern age, and especially after the advent of Hitler – that is to say, the impossibility of a literary form that assigns meaning to suffering, or represents an experience of transcendence through suffering. In consonance with this concern with tragedy, a good deal of weight is given to Nietzsche’s notion in

The Birth of Tragedy

of the roots of the genre in an experience of violent primal forces contained by artistic form – Herbst, preeminently a “Socratic” man in Nietzsche’s negative characterization of German academic culture, at one point runs across a first edition of

The Birth of Tragedy

in an antiquarian bookshop.

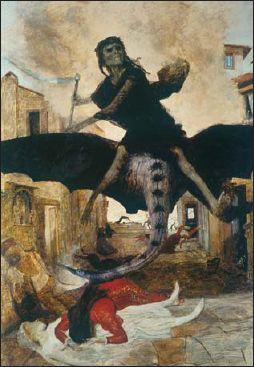

Another manifestation of Agnon’s preoccupation here with the way art illuminates reality is the attention devoted to painting, again, a thoroughly uncharacteristic emphasis in his fiction. Three painters figure significantly in the novel: Rembrandt and Böcklin, who recur as motifs in connection with Shira, and the anonymous artist from the school of Bruegel responsible for the stupendous canvas of the leper and the townscape (iii:15) that constitutes Herbst’s great moment of terrifying and alluring revelation. A look at how the three painters interact in the novel may suggest something of what Agnon was trying to say about art, and perhaps also why he found his way to a conclusion of the novel ultimately blocked.

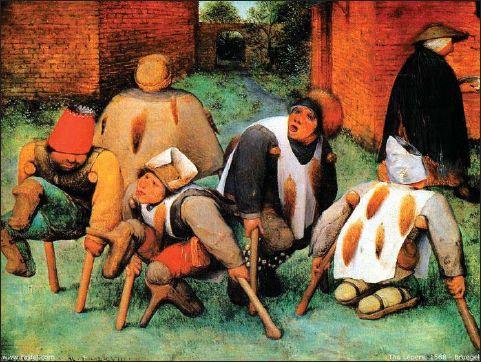

If art, or poetry, is a route to knowledge radically different from the academic enterprise that has been Herbst’s world, Agnon sees as its defining characteristic a capacity to fuse antinomies, to break down the logically marked categories – Herbst’s boxes full of carefully inscribed research notes – presupposed by scholarly investigation. The Bruegelian painting Herbst discovers at the antiquarian’s is a multiple transgression of the borderlines of reason, and that, he realizes, is the power of its truthful vision. The leper’s eye-sockets are mostly eaten away by the disease [see Fig. 1], yet they are alive and seek life – a paradox that reenacts the underlying achievement of the painter, “who imbued the inanimate with the breath of life.” The medium of the painting is of course silent, but Herbst, contemplating the warning bell held by the leper, experiences a kind of synesthetic hallucination, hears the terrible clanging sound, and feels the waves of the disease radiating out from the leper’s hand. The painting from the school of Bruegel, as I have proposed elsewhere,

*

is in its formal and thematic deployment a model for the kind of art embodied in

Shira

itself: in the foreground, the horrific and compelling figure of the diseased person [Fig.2], intimating an impending cataclysm; in the background, half out of focus, the oblivious burghers complacently going about their daily pursuits [Fig. 3]. Agnon gives us not only the artwork but also an exemplary audience for it in Herbst. The historian of Byzantium is mesmerized by the painting in a paradoxically double way: “he looked at it, again and again with panic in his eyes and desire in his heart.” The painting at once scares him and translates him to an unwonted plane of experience, because it both speaks eloquently to a universal truth of human experience and gives him back a potent image, of which he is scarcely conscious, of his own life.

The painting depicted in Book II Chapter 15 “from the school of Bruegel” does not seem to be an actual painting, but Agnon may have been drawing on elements from a number of works by Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569), see figs. 1-3.

Fig. 1: Bruegel the Elder, “The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind” (1568) – Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. (“Herbst picked up the picture and stood it up so he could see it better. The eyes were awesome and sad. Their sockets had, for the most part, been consumed by leprosy, yet they were alive and wished to live.”)

Fig. 2: Bruegel the Elder, “The Lepers” (aka “The Cripples”) (1568) – The Louvre, Paris

Fig. 3: Bruegel the Elder, Detail of “The Fight of Carnival and Lent” (1559) – Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Fig. 4: Rembrandt, “The Night Watch” (1642) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Fig. 5: Rembrandt, “The Anatomy Lesson” (1632) – Mauritshuis, The Hague

Fig. 6: Arnold Böcklin, “The Isle of the Dead” (1883) – Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Fig. 7: Arnold Böcklin, “The Plague” (1898) – Kunstmuseum, Basel