Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (56 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Despite the pressure, Shirley was not yet able to begin a new novel. Instead, she spent the fallow period absorbed in family life—which was good for a few stories, as always—and planning the sequel to

Savages

, which “obviously . . . must be called ‘On the Raising of Demons.’ ” She and the children started a garden, with raspberry bushes and radishes and carrots and lilacs. Barry, age three, had largely recovered from the asthma and pneumonia that had plagued him as a baby and was revealing his personality as a gentle, easygoing child: “our small clown,” Shirley called him. Sarah, now six, had begun to read in earnest and was placing her own rare-book orders with Louis Scher of the Seven Bookhunters. While Joanne was away at camp, Sarah spent the summer of 1955 working her way through Shirley’s entire collection of Oz books, staying up all night to read and sleeping during the day. Joanne, a precocious nine-year-old, discovered dancing and, along with the rest of America, Elvis Presley. Shirley was surprised to find that she enjoyed his music too, though

she would come to prefer the hit “Blueberry Hill,” by Fats Domino, the rhythm-and-blues singer-songwriter and pianist. “i actually like rock and roll,” she wrote to her parents—perhaps hoping to shock them—“and every evening while i am making dinner . . . laurie puts on my fats domino records, and everyone else goes away and shuts all doors and tries to listen to armstrong or presley, but fats domino can drown out any of them.”

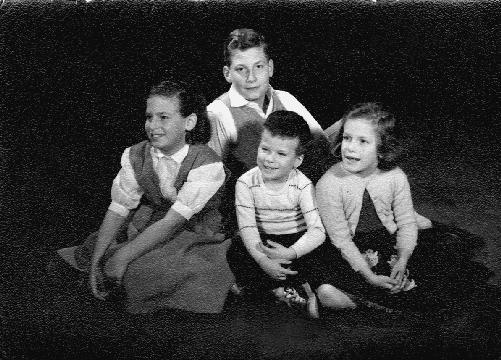

Joanne, Laurence, Barry, and Sarah, c. 1956.

At age twelve, Laurence continued to disappoint Shirley with his lack of interest in academics, but he had discovered two new skills: carpentry and baseball. “since we have been in despair all these years because he could hardly read and write, it’s nice to discover that he does have some kind of a talent,” Shirley wrote wryly. North Bennington established its first Little League, which attracted both faculty and local families, making some progress toward resolving the long-standing cold war between the college and the village. (It helped that the faculty contributed generously to the creation of a baseball field.) “Our whole family life is completely tied up with the Little League,” she wrote proudly to Baumgarten, sending the scores from Laurence’s games in lieu of stories.

Laurence also took up the trumpet, and it was quickly apparent that he had considerable talent for that as well. Shirley and Stanley decided that he ought to hear “some real jazz,” so in the spring of 1956 they took him on a tour of New York City nightclubs. The first stop was the Metropole, “loud and noisy,” with two different bands. Then Jimmy Ryan’s, “small and very fancy,” where Laurence was initially denied entry: Stanley persuaded the management that he and Shirley were the boy’s parents and would not let him drink “anything stronger than coke.” Next was Nick’s, where the manager recognized Shirley and Stanley from their days in Greenwich Village and seated them at the front table, practically underneath the band. “stanley kept having to duck his head because he was right under the trombone and laurie was delighted, because he was about two feet away from the trumpet player.” When they finished playing, she and Stanley were “limp,” but Laurence was “applauding wildly.” They ended the night at Eddie Condon’s. “at one in the morning we looked at laurie and he was sound asleep sitting up at the table, but we nearly had to drag him out to get him home,” Shirley wrote. “he kept asking to stay for just one more number.”

Much of this material found its way into magazine stories: Farrar, Straus was encouraging Shirley to put together a sequel to the wildly successful

Savages

. The company was preparing to celebrate its tenth anniversary in the fall of 1956, and Roger Straus hoped to have a new Shirley Jackson book as “an additional plume” in his hat. With the provisional title

On Raising Demons

(later the “On” was dropped, against Shirley’s wishes), the book again included a nod to her studies in witchcraft, with an epigraph describing the conjuration of demons taken from the Grimoire of Honorius, a compendium of magical knowledge from around 1800. Otherwise, the book’s demons were entirely of the household variety: Laurie and Jannie, moving steadily into adolescence; Sally, absorbed more and more deeply by her own imaginary world (one of the book’s reviewers called her “a little chip off the old broomstick”); and Barry, her sidekick and ready accomplice.

Jackson stuck closely to the winning formula she had developed in

Savages

: breezy tales of mostly harmless misadventures, relayed by a mother who is reassuringly self-deprecating with regard to her own imperfections.

As the children grew older, they could no longer be relied upon for adorable material, so Jackson increasingly sought out the humor in her own predicaments.

Demons

opens with a hilarious account of the stress of moving, from the cryptic abbreviations the moving company uses on its list of the family’s furniture and other possessions (with some difficulty, Shirley and the children figure out that “S. & M.” stands for “scratched and marred,” “M.E.” for “moth-eaten,” and so on) to the furious phone calls required in order to get the items delivered to the new house. A scene in which she repeatedly telephones the man in charge of the company, only to be told by his secretary (a moment after she hears his voice on the line) that he is away for the day or otherwise indisposed, seems too funny to be true, but in fact it comes almost verbatim from a letter Jackson wrote to a former neighbor in Westport asking for advice on how to handle her problems with the local moving company. All she changed was the man’s name.

More often, though, Jackson transformed the stories with a fictional twist. In an episode in which she takes a rare weekend away, she leaves behind a seemingly random stream-of-consciousness memo of instructions (“Barry Sunday breakfast cereal, bottle, lunch applesauce, cats milk Sunday morning, milk in refrigerator, did you leave casserole in oven Saturday night?”), which Stanley ignores, taking the children out to the hamburger stand instead. A note she actually once left before a solo trip, which included detailed descriptions of how to light the stove and prepare coffee, demonstrates just how unfamiliar Stanley was with the workings of the kitchen, like so many men of his era. (When in doubt, Shirley told him, ask Laurence where the food is.) Blatantly disregarding her mother’s advice, Jackson played up her own distraction in an episode in which she wakes up at ten thirty one morning to discover that the three older children have wandered off on their own, Sally telling the milkman that their mother has “gone to Fornicalia to live” and Jannie informing a friend’s mother that she had gotten no breakfast because Shirley “had not come home until way, way late last night.” In another of the book’s funnier moments, Shirley receives a birthday card in the mail at the wrong time of year and puzzles over who the sender could be (a person with “almost illiterate” handwriting who is so cheap as to use two-cent stamps) until she realizes that she accidentally sent to herself a card she intended for Stanley’s great-aunt.

All the comedy notwithstanding,

Demons

is pervaded by an undercurrent of anxiety that was absent in

Savages

. Much of the anxiety has to do with money: despite the Hymans’ improved financial situation, there is still never quite enough of it. Stanley keeps tabs on the cash, and Shirley resorts to subterfuge (sometimes with the children’s collusion) to win his consent for the purchase of any big-ticket item. Grocery money can be wrung out of him only “by a series of agile arguments and a tearful description of his children lying at his feet faint from malnutrition.” In order to get the electric razor she wants to give him for Father’s Day, she has to buy it from the electric company and charge it to their bill, in installments. After her car is totaled in an accident, he grumbles about replacing it but finally gives in: “since we were in debt for the rest of our lives anyway with the house payments we might as well buy a car too and go bankrupt in style.”

No casual reader of this book would dream that Jackson had actually outearned Hyman for years. With the success of

Savages

, the disparity in their incomes dramatically increased. In addition to his Bennington salary, which went up to $5200 in 1955, Hyman still got a weekly “drawing account” from

The New Yorker

of around $75 a week for his work on Comments and “Talk of the Town,” as well as for the short book reviews he was still regularly writing. But the real money to be made at the magazine was in profiles and other journalistic articles, which, despite his efforts, were not his métier. Though Hyman’s contract was renewed every year, he was only ever able to get a few long pieces into

The New Yorker

, to his great chagrin. An article he submitted in 1953, about the time capsule buried during the construction of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, was deemed to be in such bad shape that another staffer was tasked with rewriting it; he and Hyman shared the byline. Hyman’s last published reported piece, a humorous account of a visit to the Seminars on American Culture at Cooperstown, appeared in 1954. By 1958, he was once again in arrears to the magazine. In 1959–1960, he spent more than a year working on a profile of Jackie Robinson, the second baseman who made baseball history as the first African American to play in the major leagues. William Shawn accepted the piece, but it never ran in

The New Yorker

. The profile finally appeared in

The New Leader

in 1997, long after Hyman’s death.

Meanwhile, Jackson seemed able to turn just about anything into a moneymaking opportunity. In 1956, the Hymans were audited; while Stanley went over the figures with the man from the IRS, Shirley listened from the kitchen, making notes. “if i can sell the story we break even,” she told her parents. (The piece didn’t sell, but she made use of it in

Demons

.) “Nothing is ever wasted; all experience is good for something,” she would later advise in her lecture “Experience and Fiction.” In addition to her advances, royalties, and magazine sales, foreign rights were proving a significant source of revenue:

Savages

appeared in German, Italian, Norwegian, and Swedish, among other languages. Hyman’s income for 1956 totaled around $9900; Jackson’s was greater than $14,000.

In public, Hyman admitted only pride in Jackson’s earnings; he sometimes even bragged that his wife made more money than he did. Jackson, too, was openly proud of her earning power, especially in front of her parents, who had so often seen her in debt (and helped to bail her out). But she resented the amount of control he kept over their finances—as well as his criticism whenever he found her devoting time to a non-moneymaking activity, such as writing letters to relatives or friends. At one point he justified the purchase of a new dishwasher by rationalizing that every minute Jackson saved on doing housework was “potential writing time.” When

Savages

was on the best-seller list in the summer of 1953, Jackson bragged that “stanley cannot say a word about my writing such a long letter; he usually protests that all these pages would make a story.” Many of these remarks may have been made in jest, but there was a serious undertone. Later, at a crisis in their relationship, Shirley would accuse Stanley of sabotaging her literary work by forcing her to write magazine stories for money.

The financial pressure added to the stress on Shirley and Stanley’s delicately balanced marriage. In

Savages

, Stanley appeared as a kind of accidental bumbler, but in

Demons

, the tensions between him and Shirley are readily apparent. In addition to depicting him as cheap, Jackson alludes more than once to his infidelities. In one story, after a longtime female friend of Stanley’s announces her intention to come for an overnight visit, he unsubtly suggests that Shirley clean the house from top to bottom and prepare a special dinner—which she does, grumbling, as he sings the

other woman’s praises. (In a stroke of luck for Shirley, the woman’s trip is canceled at the last minute.) In another of the stories, based on an actual incident, Stanley is invited to judge the Miss Vermont contest, which involves traveling to Burlington to spend several days in the presence of a group of nubile young beauties. Shirley claims she finds the whole idea hilarious, but she finds a way to twist the knife. In one scene, the whole family is discussing the beauty pageant at the lunch table:

“Daddy is going to see a lot of girls,” Sally told Barry. She turned to me. “Daddy likes to look at girls, doesn’t he?”

There was a deep, enduring silence, until at last my husband’s eye fell on Jannie.

“And what did you learn in school today?” he asked with wild enthusiasm.

Some of the critics who reviewed

Demons

—both men and women—found this depiction overly exaggerated, as it likely was. Writing in the

Houston Post

, Derland Frost complained that Jackson portrayed her husband as “the classically dogmatic but essentially simpleminded buffoon whose main purpose in life seems to be to allow himself to be outwitted by wife and children.” Another reviewer wished that “the author’s husband had won more of a role than that of somehow hanging ominously over the dazzling prospect of every new purchase.” And a few noted the uncommon acidity of the segment about being a faculty wife, an angry piece originally published in the Bennington alumnae magazine, in which Jackson suggests that only Bluebeard, the fairy-tale aristocrat who murders his wives and hides their bodies in a room in his castle, would make a worse husband than a professor. The admissions director, concerned that the article portrayed Bennington too negatively, had all the copies of the magazine removed from display during commencement; Jackson informed her sweetly that she had already sold the piece to

Mademoiselle

.