Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (33 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

Alan had much sympathy about what had happened to me on

Jedi

, but it seemed that in all innocence I had not recognised the danger signals in the situation which I had created for myself.

The few offers of work as cinematographer which I had been given so far had come in small doses – crumbs put my way as I was probably the cheapest cameraman around and desperate to try out my new light meters. One of the promised crumbs was a small television film for Stanley O’Toole called

Island

of

Adventure

, a pilot for a proposed Enid Blyton television series which in the end was not picked up by a broadcaster. Other promised work never came through, leaving me concerned at the pattern now forming around me after my

Jedi

experience. Then again, perhaps I was just feeling sorry for myself.

Then, out the blue,

Biddy

arrived to put a smile back on my face. While I would never know how this came about, I sensed that my life was changing in this transition period. The director Christine Edzard and her producer husband Richard Goodwin, with whom I had worked on

Death on the Nile

, had phoned to offer me a pleasant little film to photograph, restoring my faith in human nature, knowing that this time I would be working with genuine people. However, what came as a surprise – and disappointment – was that Christine suggested that the camera should be kept locked off when filming. Of course this is the director’s right, especially as the director has a particular understanding of the subject matter, but I thought it a shame, as camera movement creates atmosphere, adding mood to a scene. I mentioned this to Christine, who politely listened to a second opinion before sticking with her original judgement on the matter, which of course I respected, this time without any negative repercussions.

Either way, working with the charming Christine, I found

Biddy

to be a very enjoyable experience. The story was of a prim and proper housemaid, methodical in everything she did and sure to see that everything was put away and placed neatly folded in the right place. That sets the scene for the delightful Biddy and her relationship with the family’s children.

While I was working with this very interesting director who allowed me the freedom of expression with my contribution, matters were complicated by a call from Ireland to film a test for Lewis Gilbert on a film which he would soon direct. Christine’s kindness towards me made it impossible for me to accept the job. If I had taken Lewis’s offer, then possibly my career as cinematographer would have taken off much earlier, as Lewis’s film

Educating

Rita

was so successful.

With my confidence steadily growing, I was then offered a second unit as cinematographer on

The Last Days of

Pompeii

, providing me with yet another opportunity to work under the baton of the maestro himself, Jack Cardiff, who was well aware of my dream to move forward.

Here I am reminded of a night sequence by the water’s edge that would take time to get right if it was meet with Jack’s approval. What was of no help to me or my nerves was the producer, who constantly walked up and down, making sure I noticed that he was looking at his watch. With the authority of my mentor behind me, I never wavered and refused to give in to this over-the-top intimidation. There were other snippets hardly worth a mention, but these short experiences would play an important part in strengthening my self-belief as I moved slowly towards my goal.

So to get to the point of all this waffle: the question remains – why did I agree to accept Alan’s kind offer to operate the camera on

The

Hunchback of Notre Dame

? If truth be told, I gave in to Alan’s persuasive powers because I believed that I had little chance of being offered a film as a cinematographer – at least that is what I held to at the time. However, chance had not abandoned me altogether, and the moment arrived while we were testing camera equipment for

Hunchback.

It was a timely call from Stanley O’Toole, offering me a small film to photograph,

On the Third Day –

a personal project for the producer which he would write, produce and direct himself; he was quick to point out that he had little money to splash around in his tight budget. Stanley’s offer came at a crucial point in my career after giving in to Alan’s tempting offer, though both would help to erase the sad memory of my

Jedi

experience which, as you can see, still lingered in the background. With Stanley financing the film himself it was clear that there would be little money to play with, but as far as I was concerned currency would not be an issue for me. Nor would the Herb Ross incident with Ernie Day – which I believed Stanley should have smoothed over – concern me any longer. All that now faded with time and memory; nothing would stand in my way with this big break!

Working with Stanley O’Toole over the years, it was inevitable that we would get to know each other’s strengths and weakness, particularly when it came to discussing my salary. Stanley always had the advantage in these encounters, knowing I had no agent at that time to protect my interests. Wearing his producer’s hat, crying over his ‘very tight budget’, he kept the ‘negotiations’ simple by not looking me in the face when announcing any figure he had in mind, knowing well that I might start laughing before he rejoined the real world where I exist. However, I would be prepared for these encounters where any discussions of my salary over the years would become a joke, which I suspect we both enjoyed anyway.

It happened that during our ongoing negotiations for

On the Third Day

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was speaking on the radio about the situation in the Falkland Islands. At the time we were driving around Cornwall looking for suitable locations but Stanley’s attention appeared to be tuned more into the radio with the constant updates about the military situation. With all the distraction going on in the South Atlantic this had to be the ideal if not fortuitous time for him casually to remind me for the umpteenth time of the small budget he had in mind, particularly with regard to the subject of my salary, before quickly returning to the radio for updates from Maggie on the conflict, cutting off any further thoughts I had about discussing the matter. Stanley would always pick the moment of where and when would be ideal to discuss this issue. The latest news from the Falklands on the radio provided the perfect time for my driver to plan his strategy.

I played along with his little game, trying to keep a straight face as I watched Stanley agonise as he waited on my deliberately delayed response to his ridiculous figure, at the same time knowing that I had already made up my mind, but this would come in my own time. Eventually, to put him out of his misery, I told Stanley as a friend that I would photograph the film free of charge, so now we could both concentrate on the job in hand. My relieved driver turned to me with a broad smile on his face. Stanley had won the battle this time but the fact is that my sacrifice was necessary, if only to gain that all-important screen credit of cinematographer.

The filming in Cornwall would take four weeks to complete, with the constant friendly banter between us continuing to grow. Stanley directed his first film while I photographed my second, at the same time keeping my technical camera-operating eye open for him just in case he ran into any potential problems with editing or other unforeseen issues, just as Ernie Day had done for David Hemmings on

Running Scared.

However, like Ernie, I would only intervene should it be necessary.

While I could not be sure if Stanley’s film – a horror suspense story about a man who breaks into an old headmaster’s family home to reveal himself as his unknown illegitimate son – would ever reach the cinema or television screens, it would not be the issue for me. We all have our dreams and Stanley was now fulfilling his, while at the same time pointing my career forward in the right direction; I hoped that our partnership would continue long into the distant future.

Letting my thoughts run riot, I also dreamed one day of directing a film. I am not alone in this ambitious idea, where as an experienced camera operator over many years I worked with directors who at times I believed had little or no idea of how to get the best from a scene with the use of the camera, and – dare I say – with the actors too. However, to balance this I would learn from directors who had great imagination and the courage to put their ideas on the screen. Truly this is not conceit on my part as there are many directors with camera department pedigrees: Freddie Francis, Guy Green, Jack Cardiff, Ronald Neame and Denis Lewiston, to name but a few – all cinematographers of repute and with a great deal of experience. Equally, editors also proved their worth behind the camera and were more than capable as directors, but at this time any thoughts I had of directing were just a pipe dream; I was doubtful that I would ever get the opportunity or responsibility of such high office.

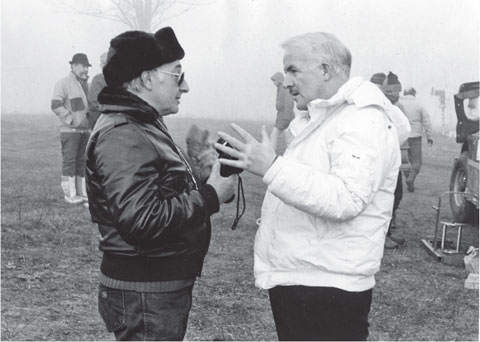

Negotiating my salary with Stanley O’Toole: ‘You agreed the deal, Alec, I can’t change it now!’

Working with Stanley O’Toole would leave me wondering where I stood in this unusual relationship: at times I felt genuine friendship towards me, while on another day he would wear his stern producer’s hat, keeping me at a distance. Recognising the danger signals, I would then back off until he came back from whatever strange mood he was in.

With the day’s schedule successfully completed I would be rewarded with an invitation to have dinner with his family while discussing the next day’s call sheet; my ever-present camera assistant Frank Elliott with his amusing charm would fit in well with the fun and games of the O’Toole household.

One night, with the meal over, Riki O’Toole, Stanley’s wife at the time, suggested that we might like to join them in a session with their Ouija board – an occasional pastime which the family apparently enjoyed. Although I admitted to being uncomfortable with this, I still agreed to watch the proceedings. I was reminded of a film scene as the lights were dimmed for atmosphere as we sat around a small table, waiting for ‘someone’ to join us. Minutes passed … nothing … total silence … You could hear a pin drop. No one spoke as we waited on a contact from the other side. What a waste of time, I thought to myself with all this nonsense.

Suddenly we were joined by a visitor from the ‘other side’; James – or perhaps Jim – now made his presence known to us. We all looked at each other, silently enquiring if anyone knew a James, but apparently none of the participants recognised any person of that name who had passed over. Still not sure about any of this stuff, I whispered to the group, hoping the spirit couldn’t hear me.

‘I know a Jim … but he’s not dead yet!’

There is no way now or in the future that I would ever want to communicate with anyone on the other side as I had no idea how to handle this situation. Even so, the other participants urged me to reply. Hoping not to offend James – or Jim – or any other poor souls who had passed over and were listening in to this ridiculous conversation, I hesitated to use the word ‘dead’ under any circumstances. Everyone was patiently waiting on my response, and I was still not sure if I wanted a chat with this silly Ouija board that was staring at me. Urged on by my silent partners, though, and looking directly at the board – as if it was Jim – I decided to go for it.