[sic]: A Memoir (2 page)

Authors: Joshua Cody

And then, from this point of serenity, of composure, I lost a little bit of my mind, as the series of chemo treatments tipped forward, tipping me forward—oddly enough, right at the pyramidical, diamondsharp point of the Golden Ratio.

“What’s the Golden Ratio?” you might well ask. Easy to explain. Now so the thing that studying music does for someone, I think, is it gives them a real acute sensitivity to form. At least that’s what it did for me. A sensitivity to where one is in relation to a frame, which could be a physical surrounding, like where you’re sitting in a Starbucks, the heat of the wall next to you as opposed to the cool open space to your right. Manhattan, being an island, is a perfect arena for such unconscious observations, like the rocky ins and outs of the Peloponnese were for the Ancient Greeks. (The Persians, like us midwesterners, were stuck with plains.) The hospital I went to, for example, is on the Upper East Side, on Sixty-Eighth Street, and its location first of all is marked by the proximity of the East River, which, even if not seen, is felt in the air—there’s usually a breeze—and by the sense of a border: the city tipping into the water like it’s on a slope, as if the relative lack of buildings there demonstrates it’s a little dangerous to build them, like in Malibu. Often there’s direct sunlight, unlike in midtown proper, where the light is so often that peculiar greenish blue because it’s mainly reflected off the glass of skyscrapers. (That fact also accounts for the light’s seeming polydirectionality: it’s always coming from multiple sources, which creates a kind of otherworldly aura or glow.) The high-rises around the hospital are dated: they were built in the 1960s, most of them, and have corner balconies: they’re built out of white brick, harkening back to the Onassian era of the Mediterranean. Less cabs, more trucks on First Avenue and York, pushing the city toward its limits and pointing beyond them. Same for the 59th Street Bridge, the least elegant, most aggressively, heavily industrial of our bridges (“our” bridges: for to live in New York, like living in any great city, is to possess it): not a joiner, but an exit. There are vacant lots, rare for Manhattan, and smokestacks, iron. You get the sense that you’re at the edge of the city. These types of observations can apply not only to space but to time: you can be on the edge of a day. This all might sound stupid, or obvious, but I notice it uncannily sometimes and I think, again, it comes from studying music, the way in

Debussy (just to pick one) the music can be wandering along for a while and you find yourself drifting, the mind is drifting, you’re almost not aware of hearing anything, perhaps you’ve even forgotten you were listening to music in the first place, and then all of a sudden the music does something: it asserts its presence and opens up to take you in and it feels like the pilot has moved the throttle and you feel motion again and the plane’s going down now, you’re definitely going down, and the sun is going down and now you can make out the Empire State

Building and it’s casting a little shadow like the little plastic model it must have been once, in New York, and later must have been again, in Hollywood, and unceremoniously (not!) you’re back in the country you were born in and you remember the odors and the way diner coffee tastes and splashes and the color of the linoleum on the floor of the bathroom you had when you were four, and you’re coming down and the plane is coming down and the century is coming down and the millennium is coming down and New York is coming down, like Paris came down and Vienna came down and Persepolis came down except the difference is that for New York you’re there to witness it, and that’s the arrogance and the humility of the living. And you are in this plane and you are in this life, and life will end like this plane trip will end and life will show you a little pale orange Empire State Building casting a long shadow like this plane is showing you as it lands.

The 59th Street Bridge, Manhattan, 1910.

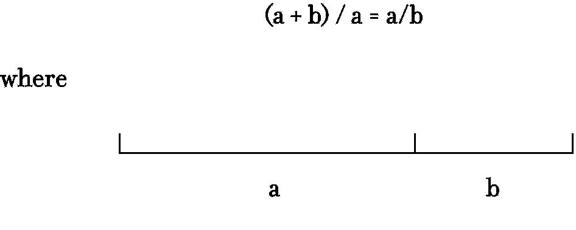

So the Golden Ratio—that’s the point in Debussy where you get that tipping feeling. A length, whether in space or in time (here, obviously, we mean time), is divided in two: the proportion of the smaller to the longer segment is the same as the relation of the longer segment to the whole. Algebraically the situation is expressed

If you’ve studied math you can easily solve this equation. (I guess.) It’s an irrational number:

(1 + √5) / 2

which is pretty close to 1.618, but it’s irrational so the actual number would go on and on to infinity, just as irrational people do.

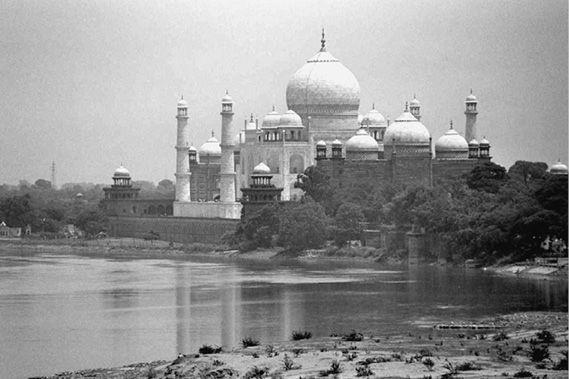

Artists, sculptors, composers, architects have intuitively hit on this proportion for centuries. No one really knows why the relationship is so powerfully pleasing aesthetically, but it seems to transcend cultures, media, ages. It’s embedded in the Egyptian pyramids, in Japanese woodcuts, in the Acropolis in Athens, in Islamic mosques, in paintings by Leonardo, who called it the

divina proportione

, the divine proportion.

Let’s say, for example—and this is what happened to me, this was how I found out—you feel a pulled muscle in your neck after lifting weights like a good young man of Midwestern stock does, and you ignore it and then you notice it again a few weeks later and you go to a doctor who tells you it’s a virus and it’s sure to go away, but for some reason you have a nagging feeling about it so you go see another guy who pushes a needle into your neck and tells you it’s probably just a virus but it could be a tumor but even if it is, it’s probably benign, and then he goes to Barbados for a week and comes back and says, tanner, that it is in fact a tumor and it is in fact malignant, and then you go see a third doctor, but the first doctor with a mustache (for that matter, a mustache and a bow tie, as if his office were in a building of cast iron and glass, with a skylight in the ceiling and a fountain at the bottom, as if he would sing with his friends in a tavern after work), and he says you should do chemotherapy twelve times at two-week intervals. The Golden Ratio would apply thusly:

Just about where it happened, just about where it tipped: the weight seems to pile up behind you like a shadow lengthening millimeter by millimeter, until it alights upon an invisible point and the scale moves level—the peak of the roller coaster: where you are, compared to where you’re going, equals what you have left, compared to how much you’ve done. Does that make sense? For some reason it reminds me of that great scene in Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece of Jewish mysticism,

Raiders of the Lost Ark,

where Indiana Jones, in Cairo and in keffiyeh—Han Solo playing T. F. Lawrence—is standing in the secret “map room” the Nazis have discovered. It’s a room with a perfectly scaled three-dimensional model of ancient Cairo, very much like the three-dimensional model of Lower Manhattan I saw at Ground Zero, after September 11, showcasing the work of another Jewish mystic, Daniel Libeskind (MA, University of Essex). Professor Jones (PhD, University of Chicago) has already explained to two government Nazi-hunters (one fat, the other thin) that the map room will divulge the hiding place of Moses’s tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments. If a prismatic medallion is stuck on the end of a staff and then fitted into a hole in the floor, a beam of sunlight, entering the chamber through a single fenestration, drawing its spotlight slowly along the room, will at a certain moment pass through the prism, focusing the sun’s rays, with a baleful intensity, into a kind of laser beam that points to the hiding place of Moses’s tablets. (Did Osama bin Laden, a man without a degree, have a model of my city in an underground map room?)

The Acropolis, Athens, Greece.

The Taj Mahal and the Yamuna River, Agra, India.

I had been such a model patient up until that night, the night of the Golden Ratio, and stepping out from the hospital into the river’s breeze on York Avenue, I suddenly realized I was Indiana Jones disguised as an Arab, and it was time to tear off the keffiyeh (what is ethnicity, anyway, besides a keffiyeh?), throw it to the ground, and go find the Ark of the Covenant. The shadow cast by the toxicity of the chemo had reached the right length: the steroids were burning through the prism, creating a laser beam. I set out on foot, fast. No question of going home, downtown, by subway: no possibility of grabbing a cab: what was of utmost importance at this moment was the traction of concrete against my shoes, the physical movement of my deteriorating body, the aging fighter, the right hook of the disease and the left hook of treatment. What if Harrison Ford had played Jake LaMotta? George Lucas wanted somebody else for Indiana Jones: he didn’t want Harrison to be seen as his “De Niro.” It was late, and the sky seemed blacker and the lights of the buildings and the cars seemed brighter than normal. I recalled reading somewhere on one of those orange pamphlets that one of the side effects of one of the drugs was “changes in vision.” Everything seemed slightly crushed in, like I was viewing things through a narrow-angled lens. The city took on the magical aspect of a miniature model—tiny points of light applied with the skill and patience of some anonymous Persian artisan. New York, which I usually felt as a massive, comforting presence around me, had tightened into the knot of a Mediterranean city. The neighborhoods were flashing by: the east sixties, now the desolate east fifties, now the skyscrapers of east midtown and now—for those of you on the left side of the cabin—the sharply soft green jewel of the United Nations building, so lonely and lovely alone against the raging sea of the East River, like helpless Andromeda, ready to be sacrificed to the sea monster, chained to the rock, the Vermont marble, a rectangle of divine proportions, Stanley Kubrick’s lunar monolith patiently housing the Ark of the Covenant.