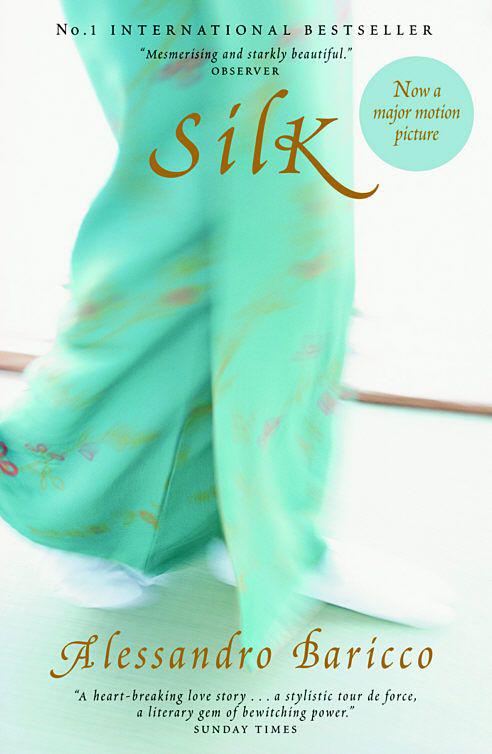

Silk

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Also by Alessandro Baricco

Copyright

A

LTHOUGH

his father had imagined for him a brilliant future in the army, Hervé Joncour ended up earning his living in an unusual profession that, with singular irony, had a feature so sweet as to betray a vaguely

feminine

intonation.

For a living, Hervé Joncour bought and sold silkworms.

It was 1861. Flaubert was writing

Salammbô

, electric light was still a hypothesis and Abraham Lincoln, on the other side of the ocean, was fighting a war whose end he would not see.

Hervé Joncour was thirty-two years old.

He bought and sold.

Silkworms.

T

O

be precise, Hervé Joncour bought and sold silkworms when the silkworms consisted of tiny eggs, yellow or grey in colour, motionless and apparently dead. Merely in the palm of your hand you could hold thousands of them.

‘It’s what is meant by having a fortune in your hand.’

In early May the eggs opened, freeing a worm that, after thirty days of frantic feeding on mulberry leaves, shut itself up again, in a cocoon, and then, two weeks later, escaped for good, leaving behind a patrimony that in silk came to a thousand yards of rough thread and in money a substantial number of French francs: assuming that everything happened according to the rules and, as in the case of Hervé Joncour, in a region of southern France.

Lavilledieu was the name of the town where Hervé Joncour lived.

Hélène that of his wife.

They had no children.

T

O

avoid the devastation from the epidemics that increasingly afflicted the European stock, Hervé Joncour tried to acquire silkworm eggs beyond the Mediterranean, in Syria and Egypt. There lay the most exquisitely adventurous aspect of his work. Every year, in early January, he left. He traversed sixteen hundred miles of sea and eight hundred kilometres of land. He chose the eggs, negotiated the price, made the purchase. Then he turned around, traversed eight hundred kilo- metres of land and sixteen hundred miles of sea, and arrived in Lavilledieu, usually on the first Sunday in April, usually in time for High Mass.

He worked for two more weeks, packing the eggs and selling them.

For the rest of the year he relaxed.

‘W

HAT’S

Africa like?’ they asked.

‘Weary.’

He had a big house outside the town and a small workshop in the centre, just opposite the abandoned house of Jean Berbeck.

Jean Berbeck decided one day that he would never speak again. He kept his promise. His wife and two daughters left him. He died. No one wanted his house, so now it was abandoned.

Buying and selling silkworms, Hervé Joncour earned a sufficient amount every year to ensure for him and his wife those comforts which in the countryside people tend to consider luxuries. He took an unassuming pleasure in his possessions, and the likely prospect of becoming truly wealthy left him completely indifferent. He was, besides, one of those men who like to

witness

their own life, considering any ambition to

live

it inappropriate.

It should be noted that these men observe their fate the way most men are accustomed to observe a rainy day.

I

F

he had been asked, Hervé Joncour would have said that his life would continue like that forever. In the early Sixties, however, the pebrine epidemic that by now had rendered the eggs from the European breeders useless spread beyond the sea, reaching Africa and even, some said, India. In 1861, Hervé Joncour returned from his usual journey with a supply of eggs that two months later turned out to be almost entirely infected. For Lavilledieu, as for many other cities whose wealth was based on the production of silk, that year seemed to represent the beginning of the end. Science appeared incapable of understanding the causes of the epidemic. And the whole world, as far as the farthest regions, seemed a prisoner of that inexplicable fate.

‘

Almost

the whole world,’ Baldabiou said softly. ‘Almost’, pouring a little water into his Pernod.

B

ALDABIOU

was the man who, twenty years earlier, had come to town, headed straight for the mayor’s office, entered without being announced, placed on the desk a silk scarf the colour of sunset, and asked him

‘Do you know what this is?’

‘Women’s stuff.’

‘Wrong. Men’s stuff: money.’

The mayor had him thrown out. He built a silk mill, down at the river, a barn for raising silkworms, in the shelter of the woods, and a little church dedicated to St Agnes, at the intersection of the road to Vivier. Baldabiou hired thirty workers, brought a mysterious wooden machine from Italy, all wheels and gears, and said nothing more for seven months. Then he went back to the mayor and placed on his desk, in an orderly fashion, thirty thousand francs in large bills.

‘Do you know what this is?’

‘Money.’

‘Wrong. It’s the proof that you are an idiot.’

Then he picked up the bills, put them in his wallet, and turned to leave.

The mayor stopped him.

‘What the devil should I do?’

‘Nothing: and you will be the mayor of a wealthy town.’

Five years later Lavilledieu had seven silk mills and had become one of the principal centres in Europe for breeding silkworms and making silk. It wasn’t all Baldabiou’s property. Other prominent men and landowners in the area had followed him in that curious entrepreneurial adventure. To each one, Baldabiou had revealed, without hesitation, the secrets of the work. This amused him much more than making piles of money. Teaching. And having secrets to tell. He was a man made like that.

B

ALDABIOU

was also the man who, eight years earlier, had changed Hervé Joncour’s life. It was when the epidemics had first begun to hurt the European production of silkworm eggs. Without getting upset, Baldabiou had studied the situation and had reached the conclusion that the problem would not be solved; it would be evaded. He had an idea; he lacked the right man. He realised he had found him when he saw Hervé Joncour passing by the café Verdun, elegant in the uniform of a second lieutenant of the infantry and with the proud bearing of a soldier on leave. He was twenty-four, at the time. Baldabiou invited him to his house, spread open before him an atlas full of exotic names, and said to him

‘Congratulations. You’ve finally found a serious job, boy.’

Hervé Joncour listened to a long story about silkworms, eggs, pyramids and travel by ship. Then he said

‘I can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘In two days my leave is over – I have to return to Paris.’

‘Military career?’

‘Yes. It’s what my father wanted.’

‘No problem.’

He seized Hervé Joncour and led him to his father.

‘You know who this is?’ he asked, after entering the office unannounced.

‘My son.’

‘Look harder.’

The mayor sank back in his leather chair, beginning to sweat.

‘My son Hervé, who in two days will return to Paris, where a brilliant career awaits him in our army, God and St Agnes willing.’

‘Exactly. Only, God is busy elsewhere and St Agnes detests soldiers.’

A month later Hervé Joncour left for Egypt. He travelled on a ship called the

Adel

. In the cabins you could smell the odour of cooking, there was an Englishman who said he had fought at Waterloo, on the evening of the third day they saw dolphins sparkling on the horizon like drunken waves, at roulette it was always the sixteen.

He returned six months later – the first Sunday in April, in time for High Mass – with thousands of eggs packed in cotton wool in two big wooden boxes. He had a lot of things to tell. But what Baldabiou said to him when they were alone was

‘Tell me about the dolphins.’

‘The dolphins?’

‘About when you saw them.’

That was Baldabiou.

No one knew how old he was.

‘

A

LMOST

the entire world,’ said Baldabiou softly. ‘Almost’, pouring a little water into his Pernod.

An August night, past twelve. Normally at that hour, Verdun had already been closed for a while. The chairs were turned upside down, neatly, on the tables. He had cleaned the bar, and all the rest. He had only to turn off the lights and lock up. But Verdun was waiting: Baldabiou was talking.

Sitting across from him, Hervé Joncour, with a spent cigarette between his lips, listened, unmoving. As he had eight years before, he was letting this man methodically rewrite his destiny. His voice came out thin and clear, punctuated by swallows of Pernod. He didn’t stop for many minutes. The last thing he said was

‘There is no choice. If we want to survive, we have to get there.’

Silence.

Verdun, leaning on the bar, looked over at the two of them.

Baldabiou was busy trying to find another drop of Pernod in the bottom of the glass.

Hervé Joncour placed the cigarette on the edge of the table before saying

‘And where, exactly, might it be, this Japan?’

Baldabiou raised his walking stick and pointed it beyond the roofs of Saint-August.

‘Straight that way.’

He said.

‘At the end of the world.’