Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir (11 page)

Read Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir Online

Authors: Linda Ronstadt

We hired lawyers and went to an endless, boring deposition. Herb and I rolled our eyes and giggled with each other even though we were supposed to be on opposite sides. During our lunch break, we went to eat together, and he suggested to

me that the lawsuit would drag on forever and be weighted in his favor because his brother was his lawyer and his legal bills would be far less costly than mine. “Linda,” he said insistently, “if we could agree on a figure, it would save us from having to sit in boring depositions, and the money you’ll end up paying to a lawyer could just go straight to me.” We agreed on an amount and shook hands. It took me a couple of years to pay him off, but we parted on good terms. I was sad because I was genuinely fond of Herb and still consider him one of the more interesting characters I met in the music business, but I needed someone who understood music and took a more gentlemanly approach in his business dealings. Peter Asher was a gentleman to his core.

John made an appointment with Peter and went with me to ask him to manage me. Peter agreed to do so. But a few weeks later, he called me over to his house to tell me that because he had already agreed to manage James’s sister, singer Kate Taylor, also managing me could create a conflict of interest that might be unfair to both of us—and so he would have to decline. I was disappointed, and John, who was a record producer and not a manager, agreed to fill in until I could make other arrangements.

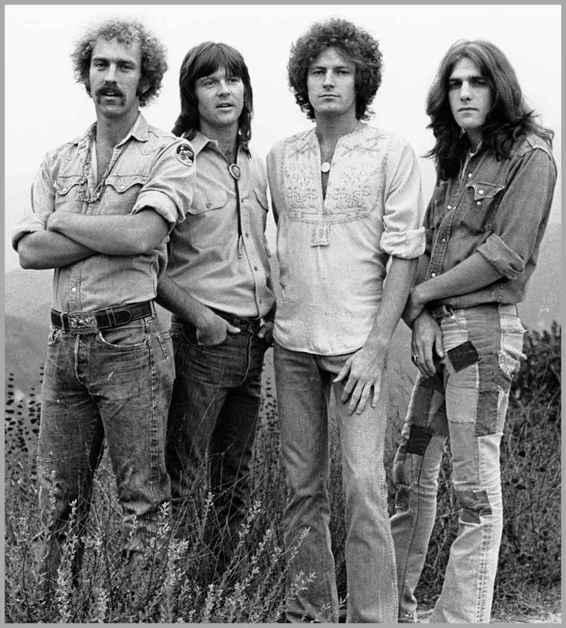

Photo by Henry Diltz.

The Eagles founding members: (left to right) Bernie Leadon, Randy Meisner, Don Henley, Glenn Frey.

5

The Eagles

J

OHN

B

OYLAN AND

I were at a Troubadour Hoot Night one evening, scouting musicians to back me up, when a Texas band called Shiloh began to play and stopped us in our tracks. They were playing my arrangement of “Silver Threads and Golden Needles,” and they were playing it really well. I was impressed by the drummer, who was a strong player with a lean, unfussy style. Better still, he seemed to have an awareness of the rhythm traditions of country music, which included the subtler, unamplified styles of bluegrass and old-time string band music. This was rare for rock drummers, who often hammered over the delicate nuances of traditional songs and rhythms, draining them of their charm. This made him ideal for playing with a singer.

John introduced himself and asked him if he would like to play some shows we had coming up at the Cellar Door, a club in the Georgetown section of Washington, D.C. The drummer’s name was Don Henley. Bernie Leadon was busy with the Burrito Brothers, so I asked John David’s Longbranch Pennywhistle partner Glenn Frey if he would come along and play guitar. We added a bass player and a lead guitarist, and Boylan played keyboards.

In those days, we couldn’t afford to get single rooms for everyone, so the guys had to double up. Glenn wound up rooming with Don and discovered why Don played so well for singers. It turned out that Don was a singer himself, and a good one. Like

Glenn, he was also an accomplished songwriter, and the two began playing music all night and ignited a musical friendship. Glenn referred to Don as the “secret weapon” and said that they had decided to form a band together.

John offered to help them and suggested that they continue to tour with me while they were waiting to get a record deal and gigs of their own. That way they would have an income, and I would have a solid band for several months. John suggested they get Randy Meisner to play bass. Randy had just recently left Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band and John thought he was a strong bass player and a great high-harmony singer. I suggested Bernie Leadon, also a strong singer, to play guitar. They liked one another and started to work together right away.

One day they needed a place to rehearse their vocal parts. John David offered the living room of our little house on Camrose Place. The room wasn’t very big, so we went out to the movies to give them some space. When we walked in a few hours later, they sounded fantastic. They had worked out a four-part-harmony arrangement of a song that Bernie and Don wrote and had spent some time getting their vocal blend just right. In that small room, with only acoustic guitars and four really powerful voices, the sound was huge and rich. They called the new song “Witchy Woman.” I was sure it was going to be a hit.

6

Beachwood Drive

Photo by Henry Diltz.

J

OHN

D

AVID AND

I moved into an apartment on North Beachwood Drive, under the Hollywood sign. We took it over from Warren Zevon and his girlfriend, Tule, who needed space for their small child. It was in a charming Mediterranean building, constructed in the 1920s, with large Palladian windows that bathed our living room in California sunshine. The apartment had battered hardwood floors, a wood-burning fireplace, and enough room for John David’s baby grand piano. MGM Studios had a sale, and I bought some old lace curtains that had been used on one of its movie sets and hung them on the windows.

There were four units in the apartment complex. Harry Dean Stanton, the actor, lived in the back over the garage. He and I struck up a friendship right away because he loved the Mexican huapangos that I knew, and he had learned to sing and play them on his guitar. Sometimes we would go watch him

perform them at McCabe’s, the performing space managed by my old Stone Poneys’ bandmate, Bob Kimmel.

Lawrence “Stash” Wagner, guitarist for the group Fraternity of Man, lived with his wife and child in the tiny ground floor unit. He had cowritten that immortal song with Elliot Ingber, featured in the Dennis Hopper film

Easy Rider

, “Don’t Bogart That Joint.”

John David and I lived on the top floor, and comedy writer Bill Martin, who later went on to a long career as a TV writer and producer, lived directly below us. Bill coined a phrase when he wrote a deeply philosophical song called “The Whole Enchilada Marches On.” He was a funny guy who hid an alert intelligence behind a half-lidded, slow-moving exterior. His apartment was fitted out with the latest hippie essentials. He had a great stereo system with big speakers, a beanbag chair, and a water pipe. He and his wife had a knack for horticulture and grew their own incredibly strong marijuana in terra-cotta pots.

They took pride in their hospitality. This consisted of settling a guest comfortably in the beanbag chair, playing Otis Redding loud enough to induce hemorrhage, and pounding paralyzing doses of marijuana in a water pipe. With the guests immobilized by cannabis, Bill would tell a story of the grisly murder that had apparently been committed in their apartment before they occupied it. At the story’s climax, he would flip back the rug to show a large bloodstain that had never come out of the floor.

John David and I, both avid readers, were happy to have the quietest space in our little complex, where we could hole up with our books and our music. He wrote a lot of good songs in that apartment, including “Faithless Love,” “Prisoner in Disguise,” and “Simple Man, Simple Dream,” all of which I would later record.

I played the Dutch housewife, scrubbing and applying layers

of wax to the floors, trying to coax a shine out of the old floorboards that had seen too many generations of indifferent housekeeping. While waiting for the wax to harden, I worked out my guitar parts to new songs I liked. By the time the floor was gleaming, I had the song learned.

Sometimes the doubts and fears that were generated by trying to create something of our own would circle us in a menacing way, and we would seek safety in the recordings of some of our most revered music masters. It was a great pleasure to float around in these little pools of perfection, happy to be relieved of the intimidating task of trying to invent them ourselves. Some of the standout recorded performances I remember listening to with him were “Drown in My Own Tears” on the

Ray Charles in Person

album, Brahms’s Trio in B Major played by cellist Pablo Casals, and Donny Hathaway’s masterful rendition of the John Lennon classic “Jealous Guy.” These were bricks that we tried to cement into our musical basements.

One album always seemed to finish up the evening, and we would play the whole thing straight through. It set a devastating mood and required strict concentration from start to finish. This was

Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely

, the record I had first heard at Alan Fudge’s house in Tucson. I learned some beautiful songs from that recording, including “What’s New,” the title song from the first collection of American standard songs that I eventually recorded with Sinatra’s arranger, Nelson Riddle.

John David was a great listening partner. The pleasure and learning experience of hearing music increases exponentially when done with someone of a deeply shared sensibility. Years later, the head of my record label thought that I was throwing away my career by wanting to record “What’s New,” with a full orchestra and a jazz band. John David understood what I was chasing, and he encouraged me.

After about a year and a half, John David moved to a house a few blocks away. We remained friends but had drifted into different webs of our own needs and interests. He was writing a lot, and I was traveling nonstop. We’ve always had feelings of affection and sympathy for each other. I still want to know about the songs he’s just written.

The last shows I played with the Eagles as my official backup band were at Disneyland in 1971 for a week of end-of-school-year festivities called Grad Night. We were on a bill with Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, plus the Staple Singers. The Disney Company paid well but had many particular requirements of the talent it booked in the park. We played several shows a night, finished up around three in the morning, and weren’t allowed to wander through the park in between shows. Also, our contract stipulated that I was required to wear a bra, and my skirt had to be a certain number of inches from the ground while I was kneeling.

When no one was onstage performing, the Eagles played poker with Smokey and the Miracles in the backstage artists’ lounge. I prissed around the room hoping to get Smokey to notice me. He didn’t. It would be hard to overstate the impact of Smokey Robinson’s magnetism. First of all, there are his beautiful gray-green eyes. After that is his cool flame of devastating charm that makes women sigh and men admire. Failing to impress him in any way, I went home and started learning his songs. A few years later, I had big hits with two songs that he wrote, “The Tracks of My Tears” and “Ooh Baby Baby.” He invited me to sing them with him on the Motown twenty-fifth anniversary television special in 1983, which also featured Michael Jackson singing “Billie Jean” and performing the moonwalk for the first time in front of a national audience. Smokey was unfailingly

supportive and gracious, but my knees were knocking together. Singing “Ooh Baby Baby” while staring into Smokey’s eyes was both intimidating and exhilarating, and remains one of the highest peaks of my career. In 2009 I listened to Smokey speaking as one musician to another in a most encouraging, inclusive, and generous way as he gave the commencement address to the graduating class of the Berklee College of Music. We were both awarded honorary doctorates.