Sisters in the Wilderness (16 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Catharine's gentle anecdotes reflected her inability to “read” the people in Upper Canada, as anyone in England could unconsciously “read” their fellow countrymen by their body-language, accents and attitudes. Catharine always saw the best in people and was rarely censorious. She had been warned about the “odious manners” of native-born

Americans, but once she had got to know a few Yankees, she was agreeably surprised to find them “for the most part, polite, well-behaved people.” Susanna, in contrast, was unsettled both by her failure to understand the strangers she met and by her inability to position them in relation to herself. So her vivid descriptions of dishonest land-dealers, thieving neighbours and disappearing servants were designed to shore up her flagging sense of superiority to all these uncouth strangers, as well as to entertain her audience. She called Uncle Joe, the bankrupt farmer from whom John had bought the Hamilton Township property, a “weasel-faced Yankee.” She described the neighbour whose family constantly borrowed articles from the Moodies and never returned them as a “bony, red-headed ruffianly American squatter.”

Susanna was impressed with the Traills' newly completed log house, which they had named Westove, after the Traill family property in the Orkneys. In a humid summer it benefitted from the breeze off the lake because it was set on a little peninsula, referred to by Catharine as “the Point.” On the ground floor there was a kitchen, a large parlour with a bedroom off it, a pantry and a storage closet. Thomas had hung maps and prints on the parlour walls; Catharine sewed curtains of green cambric and white muslin for the windows. An open staircase led to an upper floor that would later be divided into three bedrooms. Below the kitchen was a cellar in which potatoes, turnips, carrots and onions could be stored through the winter. The rooms were dark; windows were small, to ensure a warm interior during Canadian winters. But through a small pane of glass in the parlour door there was a view of Lake Katchawanooka.

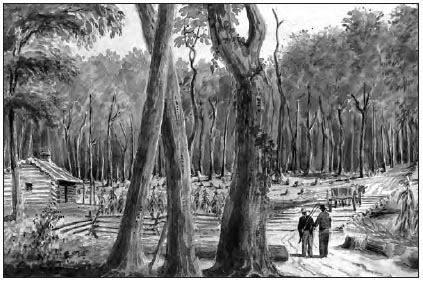

Susanna was less delighted, however, with her first sight of the real “bush,” as opposed to the cleared land close to the Front. The clearing around the Traills' house “was very small,” she noted, “and only just reclaimed from the wilderness, and the greater part of it was covered with piles of brushwood to be burnt the first dry days of spring. The charred and blackened stumps on the few acres that had been cleared during the preceding year were everything but picturesque; and I concluded, as I turned away, disgusted, from the prospect before me, that there was very little beauty to be found in the backwoods.”

A bush farm in the 1830s: the sight of corduroy roads and acres of stumps discouraged many settlers. (

Bush Farms near Chatham

: watercolour by Philip J. Bainbrigge.)

The two sisters spent the first weeks of 1834 sitting together in front of the Traills' Franklin stove, nursing their babies and reestablishing their old intimacy. The snow melted slowly that spring in the Peterborough district. John Dunbar Moodie supervised work on his own cedar log cabin, about one mile north along the shoreline from the Traills' residence. Then he turned to the question of how to clear his land. He had extended his sixty-six-acre holding on Lake Katchewanooka by spending more of Susanna's legacy on a further three hundred acres (paying, he admitted to Tom and Sam, an outrageous price for some of this uncleared land). He spent yet more of the legacy on the tools and labourers to help clear the property. Each labourer was paid on a piecework basis: eleven to twelve dollars for chopping, logging and fencing an acre of hardwood land, and fourteen dollars if pine, spruce and hemlock predominated. His spending didn't concern his wife; Susanna trusted his judgment. Besides, it was easy for her to shrug off

any worries in Catharine's company. Catharine enthused about how beautiful the summers were and laughingly dismissed Susanna's fears of wild beasts bounding out of the woods.

Soon the two women were strolling down the newly trodden path through the forest to inspect progress on the Moodie log house. It was larger than the Traills', and the ground floor was already partitioned into a parlour, kitchen and two small bedrooms. A fire was lit in the stove, and there was a plume of smoke from the chimney. Despite its dirt floors and the chinks in its walls, it was “a palace when compared to the miserable hut we had wintered in during the severe winter of 1833,” observed Susanna. “I regarded it with complacency as my future home.”

As the days lengthened, and the ice on Lake Katchewanooka turned grey and rotten, Catharine wrote home to tell their mother that, “My dear sister and her husband are comfortably settled in their new abode ⦠we often see them.” The two women spent a lot of time reminiscing about Suffolk. They liked to chat about “sweet, never-to-beforgotten home, and cheat ourselves into the fond belief that, at no very distant time we may again retrace its fertile fields and flowery dales.”

By the first week in May, the maples, oaks and birches around the Moodies' and Traills' cabins were in leaf. Soon there was a carpet of trilliums and lady's-slippers on the forest floor. At the lake's edge, the pale spikes of wild rice waved gently in the breeze. John Moodie bought a canoe, to which (ever the Orkney lad) he attached a keel and sail. Whenever possible, he and Susanna would skim across the lake's surface. Susanna's letters home were now almost as chirpy as Catharine's, as she began to see the landscape through her sister's eyes. There was no more talk of “gloomy woods.” Susanna rhapsodized about “the august grandeur of the vast forest” which cast “a magic spell upon our spirits.” Her poetry reflected her happiness:

Come, launch the light canoe;

The breeze is fresh and strong;

The summer skies are blue,

And 'tis joy to float along.”

One of the most memorable expeditions the Moodies ever made was up Lake Katchewanooka into Clear Lake and from there to Stony Lake (or Stoney Lake, as it is still sometimes spelled). John, Susanna and their two little girls set off at dawn and arrived after a couple of hours at Young's Point Falls, where the jovial Irish miller, Mr. Young, invited them to dine with his family. To Susanna's amazement, his two daughters produced a lavish feast of “bush dainties,” including “an indescribable variety of roast and boiled, of fish, flesh and fowl,” plus “pumpkin, raspberry, cherry and currant pies, with fresh butter and green cheese (as the new cream-cheese is called), molasses, preserves and pickled cucumber.” The Moodies left their daughters with the Young family and paddled on through Clear Lake, an “unrivalled brightness of water [which] spread out its azure mirror before us.” At length, the Moodies reached Stony Lakeâa dramatic piece of water lodged in a geological fold, where the stark granite of the Canadian Shield meets the soft sandstone of the St. Lawrence Valley. “Oh, what a magnificent scene of wild and lonely grandeur burst upon us as we swept round the little peninsula, and the whole majesty of Stony Lake broke upon us at once,” Susanna wrote later in

Roughing It in the Bush

. “Imagine a large sheet of water some fifteen miles in breadth and twenty-five in length, taken up by islands of every size and shape, from the lofty naked rock of red granite to the rounded hill, covered with oak-trees to its summit: while others were level with the waters, and of a rich emerald green, only fringed with a growth of aquatic shrubs and flowers. Never did my eyes rest on a more lovely or beautiful scene. Not a vestige of man, or of his works, was there.”

Susanna was right: Stony Lake was almost pristine wilderness. Its shores were still untouched by loggers, and only a handful of settlers had ever paddled across its surface, threading their way through its picturesque isles. The local Chippewa treasured the lake as a source of birchbark,

wampum grass, wild onions and game. They venerated its tranquillity and tried to keep Europeans away by telling them stories about rattlesnakes and wild beasts. Now Susanna stared around her at the landscape, “savage and grand in its primeval beauty.” She admitted to herself that, “filled with the love of Nature, my heart forgot for the time the love of home.”

Susanna was already expecting her third child when she arrived at Lake Katchewanooka. Encouraged by the good reports of immigrant life that reached England from both of her sisters, Agnes Strickland composed some cheerful verses in doggerel for her brother-in-law, John:

It affords me much pleasure,

To hear how your treasure,

Increases in land and in money.

And I give you great joy

On your hopes of a boy

To feed on your butter and honey.

And in the meanwhile,

Baby Aggie's sweet smile,

And Katie's gay prattle must be

A fund of sweet mirth

As you sit by your hearth,

With Susie at breakfast or tea.

John's hopes for a boy were answered: in August 1834, John Alexander Dunbar (always known as Dunbar) was born.

Both Susanna and Catharine had come to childbearing relatively late, but now they too were caught up in the exhausting cycle of frequent pregnancies and births. Susanna would have seven babies within eleven years, her first when she was twenty-nine and her last when she was forty. Most of her pregnancies were difficult and her labours were long; she often thought she was going to die. Catharine spaced out her nine pregnancies a little more: she was thirty-one when James was born and forty-six when the last of her children arrived, in 1848. No letters survive

describing the backwoods births, when doctors were always miles away and women had to rely on friends like Frances Stewart (and later Catharine herself) to be midwives. Neither woman would have written such letters: in the nineteenth century, the messy business of childbirth was

never

mentioned in polite society or literature. In Britain during this period, an allusion to a woman being “with child” or “lying in” was considered the height of indelicacy. (During the early 1830s came the first whimsical mentions of babies being found under gooseberry bushes.) The modern imagination recoils from the idea of giving birth in a log house, with the wind howling outside, flickering candles providing the only light and raw whisky the sole source of pain relief. The bush abounded with stories of women who died either during childbirth, or because puerperal fever set in afterwards, or because the strain of too many pregnancies caused heart disease.

Motherhood came as naturally to Catharine as breathing. It was the most meaningful activity in her life. She was always prepared to give more love than she took, and she saw no conflict between her family and her impulse to write. Since her first child didn't arrive until after she had reached Peterborough, and while she was staying with friends, she had been able to enjoy her first few weeks with him. She always hugged and kissed all her babies and treated her offspring as children long after they had grown up. Thomas was a distant parent, but Catharine made up for him. She taught her toddlers little prayers, and she read to them as they got older. She made her daughters rag dolls out of scraps of fabric. She led her brood on long, exciting walks through the forest, showing them where the deer gathered at the water's edge and how to collect frog spawn. Soon the window sills and shelves were as loaded with treasures as the window ledge of Catharine's Reydon Hall bedroom had been. The Traill children responded to their mother with deep affection, mixed (as they got older) with exasperation provoked by her suffocating love. The Traill cabin exuded warmth, with its constant smell of baking, its patchwork quilts (Catharine was an expert quilter, who loved quilting bees) and a fire that blazed brightly in its hearth.

Catharine's homemaking gifts even succeeded in cheering up Thomas, for whom life in the backwoods was proving a ghastly disappointment.

The dynamics in the Moodie cabin, a mile down the lakeshore, were quite different. John was an indulgent, loving father who could always be persuaded to play a tune on his flute or get down on hands and knees and pretend to be a bear. But Susanna was never entirely at ease as a mother. Tense and emotionally needy, she could never embrace her maternal role whole-heartedly. The writing impulse gnawed at her; she did not put her children's needs first in the same unthinking way that Catharine did. She was not a natural hugger like Catharine, and although she loved her babies, she resented their demands. It had been hard enough to make the journey from Reydon Hall to Cobourg with a baby in her armsânow she had to organize her new log house with two little girls underfoot, plus a newborn infant. She taught her family to read, but she didn't have Catharine's patience with their temper tantrums or squabbles. Dolls irritated her: as a child she had preferred frogs, and she thought rag dolls were a silly waste of time. She and her daughter Agnes often clashed, since little Aggie was just as willful as her mother. It didn't take Aggie long to discover that Aunt Traill's cabin was more convivial, and that Aunt Traill always seemed to have more time for her than her own mother did. The Moodie children scampered along the forest path to the Traill cabin whenever the opportunity arose.