Sisters in the Wilderness (45 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

With every passing year, more of the forest disappeared and the log booms from Clear Lake down the Otonabee River grew larger.

Susanna's two nephews, Roland and George, had a particular interest in showing off the delights of Stony Lake. They co-owned the eighty-foot

Chippewa

with its nineteen-horsepower engine. Roland Strickland, one of the most important timber merchants in the area, used the steamer in the spring to tow his log booms from Stony Lake to Lakefield, and he was eager to drum up passenger traffic for the vessel during the summer months. Aunt Moodie, the well-known author, might be very useful in his campaign to promote the attractions of the waterways above Lakefield. She still received invitations from Montreal magazine editors to contribute to their publications: perhaps she might turn her descriptive talents to the Strickland enterprise?

As the

Chippewa

churned through the water, Catharine chatted away to anyone who settled near her, but Susanna was silent as she eagerly searched the scenery for familiar landmarks. As she gazed out the cabin window at the east shore of Lake Katchewanooka, she could scarcely make out the property on which she and John had worked so hard in the 1830s. She knew from her visit in 1865 that their old house had collapsed, but only now, as she took in the entire setting, did she appreciate the

change in the landscape that ruthless logging had wrought. “The woods about it are all gone, and a new growth of small cedars fringes the shore in front,” she wrote later to her son-in-law, John Vickers. “There is a tolerable looking modern cottage on the spot that the old log house once occupied, and the old barn survives on the same spot on which it was built, more than 30 years ago, but the woods that framed it are all down, and it has a bare, desolate look.”

To Susanna's eyes, the land looked plucked and shaved with its stubble of stumps. The giant pines, oaks and maples that had topped the skyline were felled, and wispy second-growth birch and cedar were only starting to replace them. Huge quantities of lumber had been taken out of the area. The limestone falls down which water had once roared and foamed from Clear Lake had been blasted out in 1871 to make a lock, so that logs could be floated into Lake Katchewanooka more easily. Banks that were once covered in brilliant red cardinal flowers and orange tiger-lilies had been flooded to make a millpond. The magnificent emptiness of sparkling Clear Lake was interrupted by scattered habitation along its west shore. Susanna, who did not share her sister's concerns about vanishing species, was happy to see these signs of life. She decided that “a pretty Catholic church, and burying ground, and a small picturesque group of cottages, gives an air of civilization to the once romantic place.”

In 1835, the Moodies had pulled their canoe up at the mill by Young's Point Falls and been served a feast of “bush dainties” by the Young family. Susanna had been particularly startled to be offered coffee that had been boiled in the frying panâ“for the first and last time in my life,” she would remember thirty-seven years later. Now, Susanna was delighted to discover that the recently appointed master at the new lock between Lake Katchewanooka and Clear Lake was none other than Pat Young, son of the old miller: “He greeted me with intense Irish glee, and asked after the two pretty little girls he carried down in his arms asleep to put in Moodie's canoe at night,” she told John Vickers, Katie's husband. “And sure, was he not delighted to hear that they both had

married Irish husbands and that little Katie was the mother of nine children. âSure, she was always the clever stirring little thing.'”

The steamer continued through Clear Lake, and the temperature rose in the

Chippewa

's cabin as the hot yellow sun climbed in the sky. Susanna fanned herself with the latest issue of the

Canadian Monthly and National Review

, and Catharine undid the button at the throat of her black gown. Finally, when the sun was directly overhead, the

Chippewa

nosed its way into Stony Lake. Although thirty years of logging had wiped out the mighty oaks and white pines from its shoreline, the lake itself was as dramatic as Susanna recalled. She stared about her at the great red-granite rocks along the north shore, heaved steeply up “like the bare bones of some ancient world.” She looked at the reflections of dark woods “frowning down from their lofty granite ridges” into the cold, blue water. She heard Percy insisting that there were over 1,200 islands, and she wondered how long it would be before this marvellous, vast, lonely place became as popular amongst sightseers as the English Lake District.

Thanks to the efforts of the Strickland family, it didn't take long for Stony Lake to be discovered. The first tourists started arriving to disrupt the “wild and lonely grandeur” as soon as there was a regular steamer service each summer through Lake Katchewanooka and Clear Lake. And three years after Susanna and Catharine took their trip, a new train service from Peterborough to the Lakefield wharf doubled the steamers' business. Soon the fighting qualities of Stony Lake muskellunge, the delicate pink flesh of its salmon trout, the profusion of private islands, the azure clarity of its waters and the abundance of deer, partridge and ruï¬ed grouse in the surrounding woods were famous amongst fishermen and hunters as far south as Ohio and New York. Local entrepreneurs built shoreline hotels with well-stocked bars and acted as guides for sportsmen. The

Canadian Illustrated News

named Stony Lake “possibly the prettiest locality in Canada.” In 1893, Catharine's daughter Kate bought a three-acre island, Minnewawa, where Catharine spent happy summers. She slept in the rustic cabin and delighted in the island's “

most

beautiful oaks and pines,” as she told her son William, “and the wild

picturesque outline of the rocky mounts and deep valleys.” Within twenty years of Susanna's and Catharine's summer trip in 1872, the whole area had acquired a new name, the Kawartha Lakes (a corruption of the Ojibwa word

kawatha

, meaning “bright waters and happy land”), and become an established part of the summer cottaging ritual for many Canadian families.

In 1872, however, the two sisters were still looking at an empty expanse of glistening water and an unbroken shoreline. As the

Chippewa

's paddle slowed, and the vessel came to a halt about twenty-five miles from Lakefield, the men in the party retrieved their fishing rods and baited their hooks. The Reverend Mr. Clementi and Percy Strickland were particularly lucky, and soon several plump black bass and salmon trout were gutted and ready to be fried on a portable stove. They made “a capital dinner,” in Susanna's opinion. Then the party disembarked on the north shore, where there was a natural landing place, called “Julien's landing” after an old French-Canadian fur trader who had built a shack there. Kate Traill set off to climb a nearby hill, called “the big sugar loaf rock,” while the elderly members of the party sought the shade of the woods. Some aspects of the wilderness had not changed in three decades: the black-flies and mosquitoes were still relentless. Catharine, hot on the trail of a delicate fern that she just

knew

lingered in these woods, brushed them off with an imperious wave of her hand. But Susanna had

never

made the best of things, and she was not about to start now. As she angrily tried to swat the insects, she almost stepped on a snake. It was enough to send her marching back on board. Nevertheless, she described the trip to friends as “a grand party.”

After she was widowed, in 1869, Susanna had been slow to take up Catharine's invitations to stay with her at Westove, in Lakefield. Susanna never displayed either the sense of family or the instinct for survival that Catharine always had. When Catharine was vulnerable, she retreated without hesitation into the comforting Lakefield fold of the Strickland clan. She had done this both in 1832, when the Traills first arrived in Canada, and in 1859, after Thomas Traill's death. But Susanna floundered

after John's death, just as the Moodies had floundered after their arrival in Upper Canada in 1832. She had no roof to call her own, and she spent the rest of her life ricocheting amongst various friends and relations. The trip to Stony Lake took place at the start of one of her longest sojourns with Catharine at Westove, after Susanna had tried and rejected a variety of other options.

Immediately after John's death, Susanna had joined her youngest son, Robert, in Seaforth, sixty miles northwest of Toronto. Of Susanna's five children, only her youngest son had felt the full force of this passionate woman's love. Robert had been born in the relative comfort of the Belleville years. By the time he was a toddler, Susanna had lost one child in infancy and another child, Johnnie, in a drowning accident. Little Robert was infinitely precious to herâand like his father, he could always raise her spirits. After John's death, he was the first to insist that Susanna should come and live with him. He had recently been appointed stationmaster at Seaforth, which was on the Grand Trunk Railway branch-line between Goderich and Stratford. His offer to Susanna was more than generous, since it meant that he would have to support, on a very limited salary, not only his delicate wife Nellie and their three small children, but a mother and a mother-in-law who couldn't stand each other. They were all crammed into a badly built, four-room house, the front door of which opened directly onto the platform. Every time a train thundered by, or drew to a shuddering halt, the house shook. Nellie's mother, Mrs. Russell, constantly shrieked at the children or slapped them, setting off gales of tears. Susanna spent most of her time in her own bedroom, painting, knitting or writing, and wishing she had somebody to talk to. “Ah my dear sister,” she wrote to Catharine. “My poor, sore heart is so

empty

â¦.The days seem so long and sad.”

Susanna, alone and lonely.

After a year of the chaos in Robert's household, Susanna had had enough. Catharine entreated her sister to come and stay with her, but Susanna yearned to return to Belleville and John's grave. “Whenever, lately, I visited my husband's grave, it appeared to me such a blessed haven of rest, that I longed with an intense longing to lie down beside him. Poor darling, the harebells and Ox-eyes were growing upon his lowly bed ⦠” She decided to take lodgings in Belleville with some old friends, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Rous. But this arrangement soured, because Susanna found the Rous daughter “selfish, indolent and conceited” and Mrs. Rous's stews and hashes indigestible. “It is quite a misfortune to have been a good cook,” she wrote to Catharine. “It makes one very dainty, but I can't help it.” She moved on to rooms with Mrs. John Dougall, on the Kingston Road. But she grumbled that Mrs. Dougall was not feeding her properly, despite the ample rent she was paid. Her health deteriorated. “I have suffered awful agonies from inflammation of the stomach and bowels and frightful haemorrhage which has reduced me to a bag of bones,” she complained to friends.

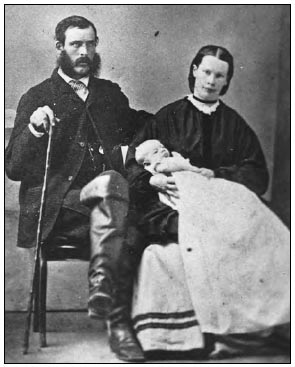

Robert Moodie, Susanna's beloved youngest child, with his wife Nellie and one of their seven children.

Susanna's health problems weren't helped by two worries. She wanted to continue her literary careerâin particular, she was eager to publish some of her husband's work. But without John's guidance, her writing and editing skills deserted her. She agreed to let George Maclean Rose, of the Toronto publishing house Hunter, Rose and Company, bring out a new edition of her own

Roughing It in the Bush

, but she couldn't even draft an updated introduction. “You must help me with matter for the Canadian preface,” she implored Katie Vickers. “I forget all the subjects dear John told me to write about on the present state and prospects of Canada.” It took her months to draft an introductory chapter in which she defended herself against her critics, celebrated the progress of the previous forty years and insisted that “some of the happiest years of my life” had been spent in the colony.

The second source of stress for Susanna was her family. Susanna's relations with her eldest four children continued to deteriorate. As adults, both Katie and Agnes found their mother exasperating. When she stayed with them, she was demanding and critical. Susanna was a little too free with her opinions on child-raising and sketch-writing (“I think her publishing has not been profitable,” she wrote to her sister Catharine, about Agnes Chamberlin, “but she would not listen to my advice”). Susanna's devotion to her husband had been particularly hard for the two boys, Dunbar and Donald, who always felt second-best. In 1866, to his mother's consternation, shiftless Donald had married Julia Russell, the sister of Dunbar's wife Eliza. Susanna had now decided that

she didn't like either of the two Jamaican sisters, and she could never resist being catty about them in her letters to Catharine (“It is only that horrid woman,” she told her sister, that prevented Donald from writing home). By the 1870s, both men were living as far away from their mother as they could afford on very limited means. Dunbar was in Colorado, in an experimental agricultural community. Donald was an alcoholic, who was constantly scrounging money from relatives and whose wife eventually left him. Neither ever visited their widowed mother, although she always kept in touch with both of them.