Size Matters Not: The Extraordinary Life and Career of Warwick Davis (2 page)

Read Size Matters Not: The Extraordinary Life and Career of Warwick Davis Online

Authors: Warwick Davis

Prologue

Expecting Someone Taller

February 3, 1970

My dad had been sitting with no little anxiety in the expectant fathers’ waiting room when he saw the doctor marching down the long corridor toward him.

The doctor stopped at the doorway and studied my father for a moment or two.

“Mr. Davis,” he said seriously, “would you please stand up?”

My father rose unsteadily.

“Hmmm,” the doctor continued in a thoughtful and slightly puzzled tone, a tone that suggested all was not as it should be. He frowned and looked my father up and down. “Walk to the door and back.”

“Excuse me?” Dad was understandably perplexed. He had been expecting the doctor to enter the room and say something along the lines of: “Congratulations, you’re the father of a healthy boy/girl,” and he would in return hand the doctor a cigar.

But in those days every single doctor was male and studied at the Macho-Man School of Medicine, where any leanings toward sensitivity, consideration, and empathy guaranteed you a Fail and a foot in the backside.

This was 1970, the year of cheesecloth and satin, when men were men and wore sideburns, perms, Brut, and gold medallions and did not, under any circumstances – unless they were wearing a white coat – witness childbirth.

“Walk to the door and back,” the doctor repeated impatiently, as if this was expected of all new fathers.

My dad did as he was told.

“You’re not unusually short, are you?” the doctor asked.

“Er . . .”

The doctor turned and started to leave the room.

“Excuse me!” my dad called after him. The doctor froze, leaning on the half-open door.

“Is it a boy or a girl?”

The doctor looked back at him for a moment and tilted his head as if deep in thought. “I’ve forgotten.” The door swung closed behind him.

At that moment the dinner trolley rattled past. Dad saw a healthy king-sized cockroach crawling happily out from under one of the plastic plates and swore that no child of his would ever be born in that hospital again.

It was touch and go for a while. The doctors didn’t know I was going to be born little and I had far too much anesthetic in my system (Mum had a Caesarean). Although I won this first round I was soon battling against pneumonia and was rushed by ambulance to Queen Mary’s special children’s hospital, my anxious parents following right behind.

A doctor suggested, rather portentously, that they christen me at the earliest opportunity. I was christened in the hospital on February 13 (my mum’s birthday).

But, despite the gloomy predictions made by the medical fraternity, and despite having to spend the first two months of my life in the hospital, I fought my way into the world. Eventually the doctors sat down with my mum and dad. This time they had a little bit more to say.

“Your son will be wheelchair-bound and dead by his teens, if he survives these first few months.”

This, as it turned out, was completely, utterly, and entirely incorrect.

Chapter One

E Eetee, Eetee Chiutatal Bok Ootu Ootu Chuu-Ock

a

“Mum, who’s George Lucas?”

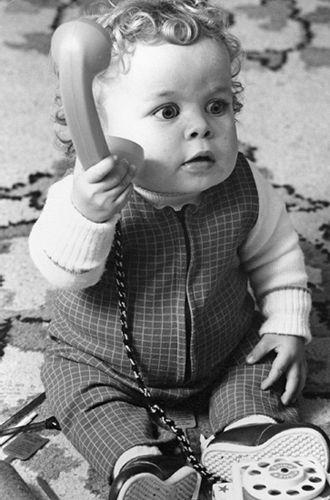

Practicing my “come hither” look.

A mini-motortrike would soon follow.

Ready for Little Chint Primary.

Sports day: Thanks to my waddle, the egg-and-spoon race became the “pick-up-the-egg-and-spoon” race.

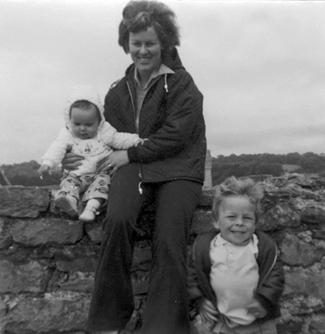

Me, Mum, and my younger sister, Kim.

Just your average family – although I’m first to admit that the dog rodeo was a touch unusual.

Me, Kim, and Dad.

Was I really that small or is that just tall grass?

What would be the dream thing you’d most like to do?” Mum asked. I considered carefully. “Think about it, Warwick, anything you want. The

most

fantastic thing you could

possibly

imagine.”

I was eleven years old and Mum was picking me up from school. Suddenly I had it. Of course! It was obvious. “Drive a go-kart!” I exclaimed.

Mum looked at me in the rearview mirror. “Come on, Warwick, what do you love more than anything else?” Hmm . . . tricky. What could possibly be better than driving a go-kart?

I’d come a long way since Mum and Dad had brought me home from the hospital. I’d grown from strength to strength – although not in height. But what I lacked in inches I made up for in explosive energy. I was a handful, albeit a small one.

While my size has of course played a huge part in my life,

b

it has never been an excuse. Indeed it came to be one of my greatest assets (alongside my charm, wit, and intellect, of course).

My size, however, had given my parents plenty to worry about for the first few years of my life, medically speaking at least. When I was a baby, my head was out of proportion to the rest of my body, and for a time the doctors were concerned that it might become too heavy for my neck, but thankfully my body gradually caught up.

My legs proved to be more problematic. I’d been born with talipes (club foot), which meant both my feet were turned inward and I stood on my ankles as I walked.

I had to wear splints every night to try to straighten them, but this had limited success, so I went for a major operation to correct this when I was two years old. The surgeons cut the back of my legs from my ankle to my knee, undid all the tendons in my legs like the shoelaces in a knee-length boot, then retied them again so I could put my feet flat on the ground.

While I was in the hospital, I was photographed several times – the doctors said they’d never seen anything like me before. I hated it; it made me feel like an exhibit in a freak show. My parents didn’t like it, either, but they felt they had to go along with the men in white coats and imagined this would help the doctors advance their knowledge. Granddad, “Poppa,” tried to comfort me by calling me his “little champ.”

Although I came home with casts on both my legs and walked like a stick man for six weeks, I refused to let them hold me back. I climbed everywhere I possibly could and took particular delight in giving my parents palpitations by balancing on chairs and tables.

It was while I was in the hospital that the doctors told Mum and Dad that I had achondroplasia, the most common genetic cause of dwarfism.

c

To some extent, it was reassuring for them to know what it was that had made me small. My parents found this time in my childhood especially difficult but they resolved that they would make sure I lived just like any other child would. The only concessions to my short stature at home were a lowered light switch in my bedroom and my very own sink.