Skywalker--Highs and Lows on the Pacific Crest Trail (26 page)

Read Skywalker--Highs and Lows on the Pacific Crest Trail Online

Authors: BILL WALKER

In one sense, it was a thing of beauty watching hikers dissect these backwater trail towns in such efficient fashion. Everybody would be scurrying around on a shoestring (“The post office is down there.” “The Laundromat is behind that building.” “Have you seen the grocery store?” “No, any idea where the outfitter and the internet are?”). It was much more mentally taxing than a day on the trail, and just as important. In a matter of hours, we routinely prepared for trips that would take most people weeks or even months to map out and provision.

Even the hikers disciplined enough to leave town on schedule would have palpably more downbeat looks on their faces than when arriving in town. Perhaps the moral of the story is that as uncivilized as we humans so often act, we are ultimately civilized beings. The sad thing is that so many of the people who got off the trail in this fashion would have been perfectly happy if they could have just forced themselves to hoist their pack, hitch back to the trail, and take the very first few steps. The challenge simply lay in beginning.

In his bestselling book,

A Walk in the Woods

, Bill Bryson spoke of the

low-level

ecstasy—so scarce in American life—that he found while hiking. I, too, retained bedrock faith that long-distance hiking was an endeavor utterly anathema to false gods, such as celebrity and money worship. Thus, it was an extremely healthy thing to do.

I had a demanding challenge ahead to make it to Canada. And it was going to be all the more difficult due to a factor that was beginning to loom larger by the day.

The average height of the Boston Marathon winner in the 20th century was just over 5’ 7”. An entire century is too long for the statistic to be a fluke. Likewise, if you look at the podium for decathlon events, you will see it disproportionately weighted towards people on the short side. In other words, being short is an advantage in endurance events.

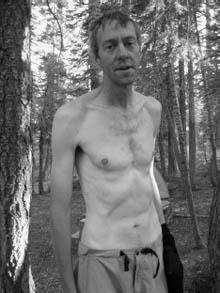

“That’s scary,” Poet immediately said, when she saw my emaciated upper body. Indeed, crushing weight loss and fatigue made me vastly more sensitive to the nighttime cold.

On a normal day, a hiker of average height with an average weight backpack would use approximately 5,000 calories. However, I probably used closer to 7,000 calories per day. For a typical five day journey from one trail town to the next, over 30,000 calories were required for me to break even. I usually carried about half of that. I don’t need to tell you the results. After 1,000 miles I was down 30 pounds, with over 1,600 miles to travel. And I was absolutely bankrupt for ideas as to how to staunch this hemorrhaging of weight.

In trail towns, I would call my mother up and anguish over this problem.

“Bill, listen to me.” she would sternly lecture me. “You’ve got to carry more food.”

“My backpack already weighs a lot more than on the Appalachian Trail,” I would shoot back. “The more weight I carry, the more calories I use up.” It was all a downward spiral.

The only surefire way to break it was to hike less miles per day. However, for the first time I was beginning to hear that

ticking sound.

It was imperative that I begin to hike

more

miles on a daily basis if I was to make it to Canada. And I badly wanted to make it.

S

omeone—somewhere—pointed out that if you are miserable when you’re alone, then the problem is that you are keeping bad company. I had hiked in the midst of

the bubble

of hikers most of the way. Now, though I was going to be alone a lot.

CanaDoug’s motto was moderation. He took great Canadian pride that he could handle whatever cold weather the hiking gods threw at him in October in northern Washington. So he was in no real hurry. But I was.

In a way, I was looking forward to it. Now, I would see what I was capable of. The gold standard on the Appalachian Trail had been 20 mile days. However, on the PCT, once out of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the gold standard becomes 25 miles per day. It required discipline for me to hike 25 miles in one day. Objectively, though, that was one of my strengths as a hiker.

Typically, I would get up soon after first light. It always maddened me that I couldn’t get off faster. There were just too many things to do—gather everything up and put in the right stuff sack, treat my feet with ointment, eat a cold breakfast, break down the tent, head off to the bushes to perform ablutions, and usually retrieve water from any nearby source. I rarely could get all this done in less than an hour; but never gave up looking for ways to reduce it.

It normally took me right about 12 or 13 hours to hike 25 miles. My walking speed probably averaged about 2.6 miles per hour, depending on the terrain and topography. This left room for a five minute break every hour during which I typically devoured a snickers or granola bar. Also, I would try to take a lunch break of at least an hour in the early afternoon. This was usually a packet of tuna, bites out of a block of cheese, triscuits and bagels and peanut butter, and beef jerky. Usually, around 8:30 I would actively begin scouting for a flat place to put my tent. Unfortunately, dinner looked a helluva’ lot like breakfast and lunch.

In

A Blistered Kind of Love

, Angela and Duffy Ballard referred to the intense solitude of long-distance hiking as

spectacular monotony.

Whatever oscillations a hiker has in morale throughout the day, the primary trend is almost always upward to some state of

grace—

or call it low-level ecstasy—by the time one sets up camp.

I can’t resist saying it, again. You’ve just got to see this PCT. It can actually stagger you with its sheer beauty.

In South Lake Tahoe, I had performed what has become a rite of passage for PCT hikers by committing an atrocity at the buffet at Harrah’s. Obviously, this wasn’t a panacea to my weight hemorrhaging problem. But at least it made me feel like I was trying something.

The trail out of Tahoe had followed gorgeous Echo Lake for miles before coming to an even more beautiful body of water, Aloha Lake. Glaciers have carved the rocky soil to give this sub-alpine region an alpine setting. Stunning granite cliff-like peaks with white snow caps tower above the shoreline of white rocks, making this perhaps the most underrated view on the entire PCT.

Often, it is the unexpected views that have the strongest impact. Or at least that’s my excuse for why I got lost for the fourth time in the last two weeks. Soon I was all the way on the far side of Aloha Lake. That was confusing because, according to my data book, I was supposed to be climbing by now. Finally, I did start precipitously winding up some steep mountain. Then, I got a break.

The only person I would see the next several hours was an older fella’ who came piking down this mysterious mountain I was now climbing. Better yet, he was a veteran local hiker.

“Excuse me sir,” I addressed him anxiously. “Is this the PCT?”

“I don’t think so,” he said softly.

“You don’t think it is, or you know it’s not?”

“It’s not the PCT.”

“Oh wow. Now I’ve got to go back a couple miles, huh?”

“Not necessarily,” he said. He then pulled out his maps and showed me a route over Mosquito Pass, followed by a labrynthine course that would put me back on the PCT in twelve miles.

An overpowering bright sun was bearing down on these white granite rocks. My high mileage goals for the day were in jeopardy, plus I wondered where I might find water if I needed it. For once, I decided to try to navigate my way back onto the PCT, instead of just putting my head between my tail and retracing my steps.

Let me say this about the Mosquito Pass trail I now doggedly pursued. When President Obama shuts down Guantanamo, they should consider transferring the prisoners here. They’d soon be begging to go back to Guantanamo. Mosquito Pass was a bug-ridden swampland.

Twice I came to turns in the trail that the man had not advised me about. All I could rationalize was that the PCT was somewhere to the east so I should probably take the right fork. Taking a break was completely out of the question given the ferocity of the mosquito attacks. Finally, I started scaling up a mountain per this man’s instructions. After about 1,500 feet in elevation gain, I came upon a PCT sign. All’s well that ends well, and my morale—so shaky for the last several hours—jumped.

Apparently the route had been a shortcut because Boo-Boo and D-Wreck—two hikers that had gone ahead of me that morning—soon came by with looks of total confusion.

“What took ya’ll so long?” I kidded them.

“Did you parachute in?” D-Wreck asked befuddled.

I cut my break short just to be able to follow them. We got to Phipps Creek where the water flowed grudgingly, but the mosquitoes attacked with an agonizing ferocity. But we all needed water, and dutifully pulled out our filters.

“Hurry up or I’m setting the tent up,” Boo-Boo commanded D-Wreck.

The God’s honest truth is the mosquitoes were so tortuous that I had to put on my marmot jacket just to fill up one nalgene bottle of water.

Boo-Boo and D-Wreck hightailed it out of there, while I still pumped. I came upon them in a couple miles where they lay inside the protective netting of their tent. They didn’t leave their tent and all I heard was discussion of how many more miles they would do tomorrow and the day after and so on. All about miles.

I lay there in my tent listening to the frequent sound of bugs’ sorties colliding against my tent netting in their attempts to get at me.

Fortunately, I had the blue majesty of Lake Tahoe to keep me company for a little while. Actually, it was for more than a little while, given that Lake Tahoe is the largest alpine lake in North America with a circumference of 71 miles around. Up until now, most of the lakes we had passed were from glacier melt. But Lake Tahoe—the second deepest lake in America at 1,645 feet—is the product of a volcano explosion.