Slayer 66 2/3: The Jeff & Dave Years. A Metal Band Biography. (14 page)

Read Slayer 66 2/3: The Jeff & Dave Years. A Metal Band Biography. Online

Authors: D.X. Ferris

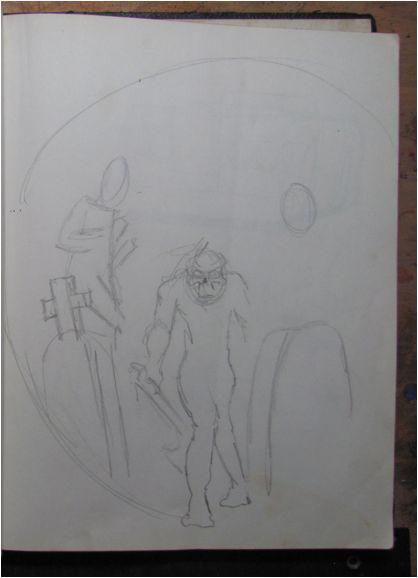

Seated at Tom Araya’s kitchen table, Jeff Hanneman took Cuellar’s marker and drew this basic diagram for the

Live Undead

art. Stick figures by Hanneman; thin incidental lines are part of a different image by Cuellar.

Live Undead

begins to take form. Cuellar drew this early sketch at the first pitch meeting at Araya’s house. Note the stencil typeface for the word “live,” which was ultimately rejected. Reproduced courtesy of Cuellar.

Shambling to life: Cuellar drew this larger sketch at Araya’s house.

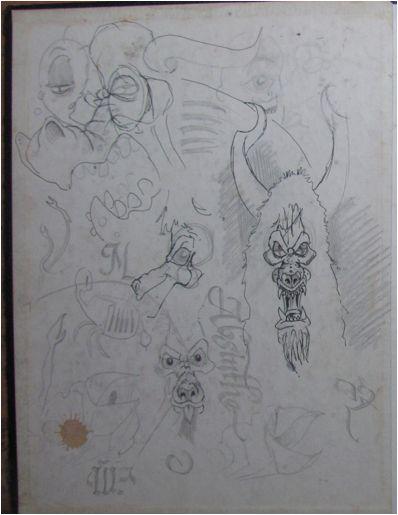

Cuellar won the artwork assignment. He drew this first draft of the

Live Undead

art at home, but the band rejected it because the zombie didn’t look like the band.

More of Cuellar’s rejected demons from

Live Undead

pitch. Drawn before the brainstorming session.

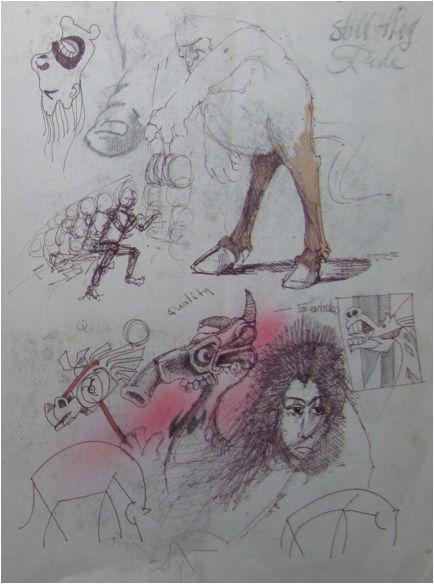

Cuellar’s minotaurs, rejected for

Live Undead

art. Drawn before the brainstorming session.

Cuellar’s rejected classical-style art for

Live Undead

. Drawn before the brainstorming session.

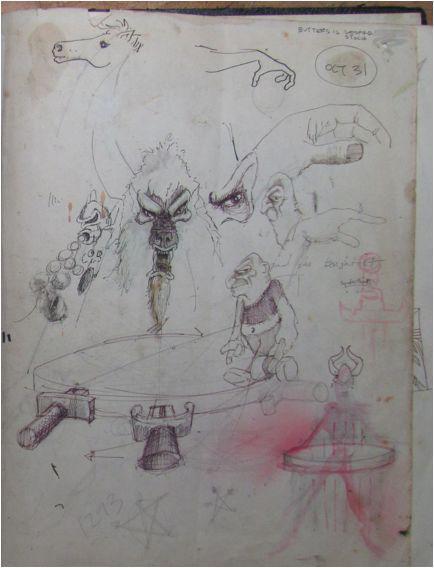

Hanneman nixed Cuellar’s proposed variations on Slayer’s pentagram logo. On right, note the faded S-shaped sword handle. Sketches by Cuellar, drawn before the

Live Undead

brainstorming session.

Cuellar — pronounced “KWAY-ar” — was an integral part of the Museum of Modern Art’s third-most-popular exhibition of all time, a show that ranked behind Picasso and Matisse. The multi-discipline creator collaborated with Tim Burton, turning the Hollywood director’s sketches into gravity-defying, three-dimensional sculptures. Cuellar’s first collaboration with Burton was a turn as the uncredited art director on 1994’s

Ed Wood

. In subsequent years, Cuellar developed a résumé working with other California artists including Sublime and Dr. Dre. He was the wardrobe stylist on the video for Sir Mix-A-Lot’s “Baby Got Back.” A decade before that bumpin’ clip, he broke into the rock world working for Slayer.

Cuellar knew the Araya family from the Chester W. Nimitz school, then a junior high, where he was two years behind Tom Araya. When Tom graduated, Cuellar fell in with John Araya, Tom’s younger brother. Cuellar became a regular at the Araya house. With tan skin and long black hair, he was frequently mistaken for another Araya boy. For a time, he worked at the shoe department at the Cudahy K-Mart, where he made friends with Lombardo.

After high school, Cuellar married young and went to work. He wanted to be an artist, and knew he couldn’t be picky about jobs. When Slayer had an opening for a graphic artist, Cuellar was working at an art supply store. He wasn’t a metalhead, but Slayer’s music seemed like a worthy application of his talents.

Cuellar’s first work for the group was a flyer for a 1982 Christmastime party held by Charlie the Rocker, a young superfan fan from South Gate, by the intersection of Liberty St. and San Miguel Avenue, near Araya, King, and Lombardo’s homes. Mimeographed on yellow letter-sized paper, the art looked cool, but the promotion backfired. Police shut down the rowdy bash before Slayer could play.

A year later, John Araya told Cuellar his brother’s band needed a cover artist. Cuellar had the inside track. Not only had he been to the Araya house and shared meals. Not only had he worked with Lombardo. But he had another sterling reference: He and Tom had taken art class from the same teacher. John had showed his older brother Cuellar’s artwork over the years. And Tom, in John’s words, “tripped on it.”

Cuellar sketched some morbid pictures and sent them to the band via John. Slayer liked what they saw. Back at home after a swing through the country, the band set up a meeting with Cuellar.

The artist wanted to make a good impression. So he bought a hardbound 11” x 14” sketchbook filled with blank white pages. In that age, books like that were hard to come by, so he was sure it would convey an image of professionalism. He penciled some elaborate sketches on the first few pages, hoping to convince the band to take a new direction with its visual approach.

Cuellar knew Tom liked his work. He was on good terms with Dave. But that wasn’t enough. Heading into the meeting, he had one goal: convince the decision maker. And, at this stage in the band’s evolving dynamic, that was Hanneman. Recalled Cuellar: “Jeff was the guy.”

The aspiring artist brought the hardback notebook and some art supplies to the Araya house. He sat through practice in the garage. The sweaty band finished their set and reconvened in the kitchen.

Sitting around the Arayas’ kitchen table, the players described what they wanted. Cuellar showed them what he had already worked up: He thought classical Michelangelo-style imagery would be a good start; later, he could incorporate demonic lighting or eerie details. Slayer didn’t want it.

Cuellar tried pitching a new Slayer logo, starting with a sword that had a capital

S

as part of its handle. They didn’t like it. He showed an alternate presentation for the swords-pentagram logo, a 3-D rendition of the logo turned on its side. But the band — Jeff in particular — was adamant about its branding and imagery even then: The logo had to be consistent.