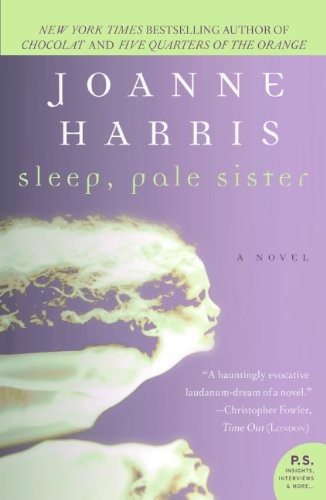

Sleep, Pale Sister

Sleep, Pale Sister

Joanne Harris

To Kevin, again

Contents

Don’t look at me that way—I can’t bear it!…

‘This I say then, Walk in the Spirit, and ye…

She lost our child, of course. Nursed by laudanum, she…

I was ill for several weeks; the wintry weather hindered…

She’s lying, you know. I was never unkind to her,…

Knave of Hearts, dear fellow, of Hearts. Kindly give me…

As the door opened and I saw him for the…

I never liked Moses Harper. A thoroughly dangerous and calculating…

For two weeks I was content to watch him and…

I’d been following her for nearly a week before I…

I was lucky that Henry was late home; it had…

I stopped at my club, the Cocoa Tree, for a…

You see, she needed me. Call me a villain if…

It was hot inside the tent and what light there…

I was beginning to become impatient; she had been in…

I could tell that Mose was annoyed that we had…

The bitch. The bitch! Bitches, both of them. As I…

Before I met Mose I never knew how bleak my…

I know, I know. I was deliberately cruel. And I…

Somehow I seemed to recognize the room. As I drifted,…

It was almost dawn when I reached Cromwell Square and…

I remember her cool, strong hand against my hair. Her…

I suppose a century ago they would have called me…

It was an accident, I tell you. I never meant…

I have little recollection of returning to Cromwell Square: it…

I didn’t see Effie the next day and, to tell…

I knew he would come: his greed and selfishness were…

I spent my entire day at the studio working on…

Five days.

The clock on the mantelpiece said a quarter past eleven.

It’s a lie: I don’t dream. There are people who…

At first I was furious.

I knew he’d come back. I’d seen him watching us…

Strange, how time can fold in upon itself like linen…

When I awoke, the sunlight was streaming through the open…

Poor Mose! And poor Effie. I suppose I should have…

I saw less of my wife that week than ever…

We were alone together, quite alone as Henry rattled about…

Four weeks passed with the aching slowness of those summer…

They came together now, like ghostly twins, their faces merging…

After that confrontation, my wife was the enemy: a soft…

As soon as I saw him leave Marta’s room and…

You have to understand that I was furious. I had…

I could not go home to Cromwell Square. The thought…

The more I thought about it, the more uneasy I…

Imagine a snowflake floating down a deep well. Imagine a…

She was lying on the bed with her hair loose,…

Behind the wall of the cemetery and the endless, exquisite…

Cursing inwardly, I tried to keep my voice soft and…

For a time beyond time there was nothing. I was…

As I watched Henry disappear along the High Street I…

Silence shrouded me as I made my way slowly back…

All right, all right. I had more than a couple…

Tabby came back from visiting her family early on the…

I awoke to the sound of bells: great clanging, discordant…

My euphoria lasted until I reached Cromwell Square. Then I…

It wasn’t till after seven that I decided to pay…

When he had gone, I paced the hall in a…

It’s amazing, isn’t it, how money disappears? I paid my…

From the moment I saw the opened present underneath the…

The snow began to fall as I left Henry’s studio.

A soft current bore me to a silent world of…

I was between the rapacious thighs of my latest inamorata…

You’d like to know, wouldn’t you? I can smell that…

It was Effie all right. They took me to identify…

The black angel stirs restlessly and I look at the…

Manuscript, from the estate of Henry Paul Chester January, 1881

As I look at my name

and the letters which follow it I am filled with a vast blankness. As if this Henry Chester, painter, twice exhibited at the Royal Academy, were not myself but some ill-defined figment of somebody’s imagination, the cork to a bottle containing a genie of delicate malevolence that permeates my being and launches me into a realm of perilous adventure, in search of the pale, terrified ghost of myself.

The name of the genie is

chloral

, that dark companion of my sleeping hours, a tender bedfellow now grown spiteful. Yet we have been wedded too long now for separation, the genie and I. Together we will write this narrative, but I have so little time! Already, as the last shreds of daylight fall from the horizon, I seem to hear the wings of the black angel in the darkest corner of the room. She is patient, but not infinitely so.

God, that most exquisite of torturers, will deign to give me a little time to write the tale which I shall take with me to my cold cell under the earth—no colder, surely, than this corpse I inhabit, this wilderness of the soul. Oh, He is a jealous God: pitiless as only immortals can be, and when I cried out for Him in my filth and suffering He smiled and replied in the words He gave to Moses from the burning bush:

I Am That I Am

. His gaze is without compassion, without tenderness. Within it I see no promise of redemption, no threat of punishment; only a vast indifference, promising nothing but oblivion. But how I long for it! To melt into the earth, so that even that all-seeing gaze could not find me…and yet the infant within me cries at the dark, and my poor, crippled body screams out for time…A little more time, one more tale, one more game.

And the black angel lays her scythe by the door and sits beside me for a final hand of cards.

I should never write after dark. At night, words become false, troubling; and yet, it is at night that words have the most power. Scheherazade chose the night to weave her thousand and one stories, each one a door into which time and time again she slips with Death at her heels like an angry wolf. She knew the power of words. If I had not passed longing for the ideal woman, I should have gone in search of Scheherazade; she is tall and slim, with skin the colour of China tea. Her eyes are like the night; she walks barefoot, arrogant and pagan, untrammelled by morality or modesty. And she is cunning; time and again she plays the game against Death and wins, reinventing herself anew every night so that her brutish ogre of a husband finds every night a new Scheherazade who slips away with the morning. Every morning he awakes and sees her in daylight, pale and silent after her night’s work, and he swears he will not be taken in again! But as soon as dusk falls, she weaves her web of fantasy anew, and he thinks: once more…

Tonight

I

am Scheherazade.

Don’t look at me

that way—I can’t bear it! You’re thinking how much I have changed. You see the young man in the picture, his clear, pale brow, curling dark hair, his untroubled eyes—and you wonder how he could be me. The carelessly arrogant set of the jaw, the high cheekbones, the long, tapered fingers seem to hint at some hidden, exotic lineage, although the bearing is unmistakably English. That was me at thirty-nine—look at me carefully and remember…I could have been you.

My father was a minister near Oxford, my mother the daughter of a wealthy Oxfordshire landowner. My childhood was untroubled, sheltered, idyllic. I remember going to church on Sundays, singing in the choir, the coloured light from the stained-glass windows like a shower of petals on the white surplices of the choristers…

The black angel seems to shift imperceptibly and, in her eyes, I sense an echo of the pitiless comprehension of God. This is not a time for imagined nostalgia, Henry Paul Chester. He needs your truth, not your inventions. Do you think to fool God?

Ridiculous, that I should still feel the urge to deceive, I who have lived nothing

but

a life of deceit for over forty years. The truth is a bitter decoction: I hate to uncork it for this last meeting. And yet I am what I am. For the first time I can dare to take God’s words for myself. This is no sweetened fiction. This is Henry Chester: judge me if you wish. I am what I am.

There was, of course, no idyllic childhood. My early years are blank: my memories begin at age seven or eight; impure, troubled memories even then as I felt the serpent grown within me. I do not remember a time when I was not conscious of my sin, my guilt: no surplice, however white, could hide it. It gave me wicked thoughts, it made me laugh in church, it made me lie to my father and cross my fingers to extinguish the lie.

There were samplers on the wall of every room of our house, embroidered by my mother with texts from the Bible. Even now I see them, especially the one in my room, stark on the white wall opposite my bed:

i am that i am.

As I passed the summers and winters of my boyhood, in my moments of peace and the contemplation of my solitary vices I watched that sampler, and sometimes, in my dreams, I cried out at the cruel indifference of God. But I always received the same message, stitched now for ever in the intricate patterns of my memory:

i am that i am

.

My father was God’s man and more frightening to me than God. His eyes were deep and black, and he could see right into the hidden corners of my guilty soul. His judgement was as pitiless and impartial as God’s own, untainted by human tenderness. What affection my father had he lavished on his collection of mechanical toys, for he was an antiquarian of sorts and had a whole room filled with them, from the very simplest of counterweighted wooden figures to the dreamlike precision of his Chinese barrel-organ with its hundred prancing dwarves.

Of course, I was never allowed to play with them—they were too precious for any child—but I do remember the dancing Columbine. She was made of fine porcelain and was almost as big as a three-year-old child. Father told me, in one of his rare moments of informality, that she was made by a blind French craftsman in the decadent years before the Revolution. Running his fingers across her flawless cheek, he told me the story: how she had belonged to some spoiled king’s bastard brat, abandoned among rotting brocades when the Terror struck and godless heads rolled with the innocent. How she was stolen by a pauper woman who could not bear to see her smashed and trampled by the sans-culottes. The woman had lost her baby to the famine and kept Columbine in a cradle in her poor hovel, rocking her and singing lullabies until they found her, mad and starving and alone, and took her away to the asylum to die.

Columbine survived. She arrived in a Paris antiquarian’s the year I was born, and Father, who was returning from a trip to Lourdes, saw her and bought her at once, though her silk dress was rotten and her eyes had fallen into her head from neglect and rough handling. As soon as he saw her dance, he knew she was special: wind the key set into the small of her back and she would begin to move, stiffly at first, then with a slick, inhuman fluidity, raising her arms, bowing from the waist, flexing her knees, showing the plump roundness of her porcelain calves under the dancer’s skirt. Months of loving restoration gave her back all her beauty, and now she sat resplendent in blue and white satin in my father’s collection, between the Indian music-box and the Persian clown.

I was never allowed to wind her up. Sometimes, when I lay awake in the middlle of the night, I could hear a faint tinkle of music from behind the closed door, low and intimate, almost carnal…The image of Father in his nightgown with the dancing Columbine in his hands was absurdly disquieting. I could not help wondering how he would hold her; whether he would dare to let his hand creep beneath the foaming lace of her petticoats…

I rarely saw my mother; she was often indisposed and spent a great deal of time in her room, into which I was not allowed. She was a beautiful enigma, dark-haired and violet-eyed. Glancing into the secret chamber one day I remember a looking-glass, jewels, scarves, armfuls of lovely gowns strewn over the bed. Among it all lingered a scent of lilac, the scent of my mother when she leaned to kiss me goodnight, the scent of her linen as I buried my face in the washing the maid hung out to dry.

My mother was a great beauty, Nurse told me. She had married against her parents’ wishes and no longer communicated with her family. Maybe that was why she sometimes looked at me with that expression of wary contempt; maybe that was why she never seemed to want to touch or hold me. I idolized her, however: she seemed so infinitely above me, so delicate and pure that I was unable to express my adoration, crushed by my own inadequacy. I never blamed my mother for what she made me do: for years I cursed my own corrupt heart, as Adam must have cursed the serpent for Eve’s transgression.

I was twelve; I still sang in the choir but my voice had reached that almost inhuman purity of tone which heralds the end of childhood. It was August, and the whole of that summer had been fine: long, blue, dreaming days filled with voluptuous scents and languorous sensations. I had been playing in the garden with friends and I was hot and thirsty, my hair standing on end like a savage’s, grass-stains on the knees of my trousers. I crept into the house quietly; I wanted to change my clothes quickly before Nurse realized what a state I was in.

There was no-one there but the maid in the kitchen—Father was in church preparing for the evening’s sermon, and Mother was walking by the river—and I ran up the stairs to my room. Pausing on the landing, I saw that the door to my mother’s room was ajar. I remember looking at the doorknob, a blue-and-white porcelain thing painted with flowers. A scent of lilac wafted out from the cool darkness and, almost in spite of myself, I moved closer and peered through the door. There was no-one in sight. Looking guiltily around me, I pushed the door and entered, telling myself earnestly that if the door had been open, I could not be accused of snooping, and, for the first time in my life, I was alone in my mother’s private room.

For a minute I was content to stare at the rows of bottles and trinkets by the looking-glass, then I dared to touch a silk scarf, then the lace of a petticoat, the gauze of an under-dress. I was fascinated by all her things, by the mysterious vials and jars, and the combs and brushes with strands of her hair still caught in the bristles. It was almost as if the room

was

my mother, as if it had captured her essence. I felt that if I could assimilate every nuance of that room I might learn to tell her how much I loved her in the kind of words she could understand.

Reaching to brush my reflection in the mirror I accidentally knocked over a little bottle, filling the air with a heady distillation of jasmine and honeysuckle. My hurried attempt to pick up the bottle only resulted in my spilling a case of powder across the dressing-table, but the scent acted so strangely upon my nerves that, instead of being panic-stricken, I giggled softly to myself. Mother would not be back for some time; Father was in church. What harm could it do to explore? And I felt an excitement, a power, looking over my mother’s things in her absence. An amber necklace winked at me in the semi-darkness; I picked it up and, on impulse, put it on. A transparent scarf, light as a breath, touched my bare arm as I passed. I raised it to my lips, seeming to feel her skin, her scent against my face.

For the first time I began to feel an extraordinary sensation, a tingling in all my body focusing more and more strongly on a point of exquisite tension, a growing friction which filled my mind with half-recognized images of carnality. I tried to make myself believe that it was the room which was making me do it. The scarf

wanted

to coil lovingly around my neck. Bracelets found their way on to my arms on their own. I took off my shirt and looked at myself in the glass and, with hardly a second thought, I took off my trousers. There was a wrap lying on my mother’s bed, a delicate, transparent thing of silk and frothy lace: experimentally I draped it around myself, caressing the thin fabric, imagining it touching her skin, imagining how it would look…

I began to feel physically faint, disorientated, the potency of the spilled perfume assailing me like an invisible army of succubi—I could hear the beating of their wings. It was then that I knew I was the devil’s creature. Some inhuman instinct impelled me to continue and, although I knew that what I was doing was mortal sin, I felt no guilt. I felt immortal. My hands, knotting and clutching the wrap, seemed possessed by a demonic intelligence: I began to caper in a frenzied, ecstatic glee…then suddenly I was frozen in sublime paralysis, doubling up beneath the force of a pleasure I had never conceived of. For a second I was higher than the clouds, higher than God…then I fell like Lucifer, a little boy again, lying on the carpet, the silk wrap crushed and torn under me, the jewels and trinkets grotesque around my scrawny limbs.

A moment of stupid indifference. Then the enormity of what I had done broke upon my head like a hailstorm and I began to cry in hysterical terror, dragging on my clothes with shaking hands, feeling my knees buckle. I grabbed the wrap and rolled it into a ball, thrusting it into my shirt. Picking up my shoes I ran out of my mother’s room and into my own where I hid the wrap up the chimney behind a loose stone, promising myself to burn it as soon as Nurse lit a fire there.

Feeling my panic abating a little, I took the time to wash my face and change, then I lay on my bed for ten minutes to still my trembling. An odd sensation of relief overwhelmed me: I had escaped immediate discovery. Fear and guilt were metamorphosed into a sense of exhilaration: even if I were punished for having been into my mother’s room, the very worst thing would never be known. It was my secret, and I kept it coiled up in my heart like a serpent. There it grew with me—and, even now, continues to grow.

I did not escape entirely undiscovered, of course: the spilled powder and perfume gave me away—along with the theft of the wrap. I admitted that part to my father: that I had gone into the room because I was curious, that I had been clumsy and had trodden on the lace of the wrap by mistake, and had torn it, and that, to avoid punishment, I had thrown the wrap into the pond. He believed me, even commending my honesty (how the devil within me laughed and capered!), and, though I was whipped for my foolishness, the feeling of relief, even excitement, did not abate. From being all-powerful, my father had suddenly dwindled: I had fooled him, lied to him, and he had not known. As for my mother, maybe she guessed something, for I caught her looking at me with an odd expression once or twice, but she never spoke about the incident and it was soon, apparently, forgotten.

For myself, I never did burn the wrap I had concealed in the chimney. Sometimes, when I was alone, I would take it from its hiding-place and touch the silken folds, until years of handling and rising smoke from the chimney turned it brittle and brown as parchment and it fell to pieces of its own accord, like a handful of autumn leaves.

My mother died when I was fourteen, two years after the birth of my brother, William. I remember her lovely chamber transformed into a sickrooom, with heavy wreaths of flowers on every piece of furniture; she pale and thin, but still beautiful to the end.

My father was with her all the time, his face unreadable. One day, passing the room without entering, I heard him weeping in violent abandon, and my mouth twisted in derision; I prided myself in feeling nothing.

Her grave was placed in the churchyard just outside the entrance to the church, so that my father could see it as he greeted his parishioners. I had often wondered how such a stern, God-fearing man had come to marry such a delicate, worldly creature. That he might have passions I could not guess at made me uneasy, and I dismissed such thoughts.

When I was twenty-five my father died. I was completing my Grand Tour at the time, and did not hear of it until all was over. It seemed that during the winter he had caught a cold, had neglected it—he hardly ever lit fires in the house except in the bitterest weather—had refused to take to his bed and, one day in church, had collapsed. Fever set in and he died without recovering consciousness, leaving me with a tidy fortune and an inexplicable feeling that now he was dead he would be able to watch over all my movements.

I moved to London: I had a certain talent for drawing and wished to establish myself as an artist. There I discovered the British Museum and the Royal Academy, and steeped myself in art and sculpture. I was determined to make a name for myself: I rented a studio in Kennington and spent my first five years accumulating enough work for my first exhibition. I painted allegorical portraits especially, taking a great deal of my ideas from Shakespeare and classical mythology, working in oils for the most part, that medium being the most suitable for the meticulous, detailed work I liked. One visitor who came to see my work told me that the style was ‘quite Pre-Raphaelite’, which delighted me, and I took care to nurture this similarity, even taking subjects from Rossetti’s poetry—although I felt that the poet, as a man, was very far from the kind of person I should like to emulate.