Smuggler Nation (20 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Not all recruits turned out so well, and indeed some proved to be better con artists than artisans. One immigrant pocketed a $10,000 advance and fled to Ireland.

53

One of Hamilton’s correspondents sent a warning: “I repeat it, Sir, unless God should send us saints for Workmen and angels to conduct them, there is the greatest reason to fear for the success of the plan.”

54

Part of the problem was the lack of documentation certifying the individual’s skills and work experience. This reflected the clandestine nature of the transatlantic crossing: machine workers attempting to move to America purposefully destroyed such documentation prior to boarding U.S.-bound vessels to avoid being detained by British port inspectors. Consequently, as Jeremy notes, hiring was based on assurances rather than records.

55

Meanwhile, many other skilled workers made the clandestine trip across the Atlantic without the prompting and assistance of a recruiter. The most celebrated self-smuggled British artisan was Samuel Slater, who started out as a teenage apprentice and then worked his way up to middle management at the Jedediah Strutt mills in Milford, England, which used Arkwright’s new water frame. Enticed by stories of opportunity and success in America, the ambitious and risk-taking Slater pretended to be a farmhand or some other nonskilled laborer and boarded a U.S.-bound ship in 1789. Leaving tools, machines, models, and drawings behind, all he brought with him was his memory. Meanwhile, Moses Brown in Rhode Island was looking for someone to figure out how to use the spinning machines he had illicitly imported. Slater took on the job and moved to Pawtucket. Brown’s smuggled machines proved inoperable, but Slater was able to cannibalize them for parts and built his own.

56

He had production up and running in Pawtucket by the winter of 1790–91.

Slater was certainly not the first to introduce the Arkwright-style water frame to America, but he was the first to turn it into a real commercial success, helping to spread the technology throughout the northeast.

57

Slater’s brother, John, also later made the clandestine move across the Atlantic and brought with him the latest cotton technology.

58

Slater-style mills proliferated throughout Rhode Island and New England, becoming the most successful early model of family-owned

textile manufactures in America.

59

By 1813, the

Niles’ Weekly Register

reported that Providence was at the center of a sprawling cotton mill production zone, with seventy-six cotton mills operating within a thirty-mile radius of the city.

60

New England cloth manufacturing boomed, increasing fiftyfold between 1805 and 1815.

61

This initial phase of illicit industrialization was a stunning success story for Rhode Island and the region.

Figure 6.2 Samuel Slater (1768–1835), the “father of the American industrial revolution.” Slater sneaked out of England in violation of strict emigration laws and was then hired by Moses Brown to work on and improve illicitly imported textile machinery in Pawtucket, Rhode Island (Granger Collection).

Historians credit Slater as being the “father of the American industrial revolution.” But Boston businessman Francis Cabot Lowell is credited with truly transforming New England textile manufacturing into a mass-production and internationally competitive factory system. Doing so involved pulling off the most remarkable case of industrial espionage in American history. Lowell traveled to Britain in 1810 for an extended stay, allegedly for “health reasons.” The wealthy Boston merchant was

not considered a rival manufacturer and therefore not treated with suspicion in local business circles. Lowell toured the Glasgow factories in the spring of 1811. Soon after, he visited other factories to obtain “all possible information” on cotton manufacturing “with a view to the introduction of the improved manufacture in the United States,” as his business partner later recounted.

62

Lowell’s bags were searched before he returned to the United States, but the British customs agents came up empty-handed.

63

What they could not search was his memory. Lowell, who had majored in mathematics at Harvard and possessed an exceptional memory, used his mind to smuggle out British industrial secrets. In addition to memorization, Lowell also apparently obtained a sketch of Radcliffe and Johnson’s patented dressing frame.

64

With the assistance of mechanical expert Paul Moody, Lowell was able to not only reproduce the machines back home but even improve on the original models. Backed by his newly formed Boston Manufacturing Company (the first company in America to sell shares as a method of raising funds), Lowell opened his first cotton mill in Waltham, Massachusetts, in 1813. Lowell’s was the first mill in the country to combine all aspects of the textile production process—from carding and spinning to weaving and dressing—in one building. This integrated cotton mill was a transformative development in the history of textile manufacturing, replacing the smaller Slater-style family-run mill operations and making the American textile industry truly competitive with Britain for the first time (though Lowell lobbied for and received a heavy protective tariff on cotton products in the Tariff of 1816). This early version of the American factory system of the nineteenth century also required much larger scale investment, epitomized by the development of an entire mill town, appropriately named Lowell in 1822.

65

Britain loosened its restrictions in phases between 1824 and 1843. The emigration bans, which cut against growing public support for freedom of movement, were lifted in 1824. Though strict controls remained on the export of spinning and weaving machinery, a licensing system replaced the prohibition system for other industrial equipment. Licensing, in turn, created opportunities for new forms of smuggling: an exporter could receive a license to ship one machine and use it

as a cover to ship a different one—gambling that port inspectors would either not check beyond the paperwork or not be able to tell the difference. Apparently, this practice was sufficiently institutionalized that illicit exporters could even take out insurance to protect them against the occasional seizure.

66

British export controls were finally repealed in 1843 with the spread of free-trade ideology. But by that time, the United States had already emerged as one of the leading industrial economies in the world—thanks, in no small part, to the successful evasion of British emigration and export prohibitions.

AMERICA’S EARLY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

strategy relied heavily on theft-aided industrialization. The nation’s early industrial revolution was made possible by the illicit acquisition of machines and machinists. But as we’ll see in the next chapter, the country’s economic development also greatly depended on smuggling-enabled territorial expansion. Smuggling played a crucial—if often overlooked—role in the push across the continent, though the form, function, and content of the smuggling was entirely different from that in the industrialization story. We therefore now turn our attention westward and examine how the West was really won.

PART III

WESTWARD EXPANSION, SLAVERY, AND THE CIVIL WAR

7

Bootleggers and Fur Traders in Indian Country

CONTRARY TO THE IMPRESSION

given in Hollywood movies, white populations pushed west into Indian country not simply through brute force. They also did it through trade, with smuggled alcohol exchanged for much-coveted Indian furs leading the way. In this sense, frontier smugglers were early pioneers, helping to lay the groundwork for westward expansion. Moreover, even as government authorities passed laws banning the sale of alcohol to Indians (an often forgotten early chapter in the history of American alcohol prohibition), they used copious amounts of rum and whiskey to lubricate Indian treaty negotiations. And the treaty terms, often involving generous land concessions and removal of tribes to more distant western territories, included dispensing millions of dollars in federal annuity payments—no small portion of which ended up in the pockets of whiskey peddlers. In other words, as part of the process of being displaced or wiped out, Indian populations were softened up by, and became dependent on, illicit supplies of “White Man’s Wicked Water”—with devastating consequences.

1

We focused earlier on the illicit side of Atlantic trade during the colonial era and the first decades of the new republic; we now turn our attention to the illicit side of trade on the frontiers of continental expansion. But even here there is a transatlantic dimension, with most of the

Indian furs bought with smuggled alcohol exported to meet booming demand in European markets.

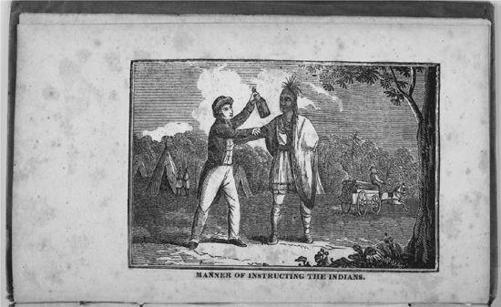

Figure 7.1 “Manner of Instructing the Indians,” frontispiece of William Appess,

Indian Nullification of the Unconstitutional Laws of Massachusetts Relative to the Marshpee Tribe; or, The Pretending Riot Explained

, Boston, 1835 (American Antiquarian Society).

Rum and Fur in the Colonial Era

The first pioneers were fur traders, not settler farmers. Their wide-reaching economic exploits in North America stimulated imperial rivalry and territorial ambition.

2

The trade began early on in the colonial era and rapidly expanded in the first decades of the nineteenth century. The scramble for profitable pelts was inherently expansionist. Sea otters, beavers, raccoons, and buffalo were an exhaustible natural resource. Their depletion through intensive hunting pushed ambitious traders to venture into new lands, often trading alcohol for Indian pelts.

3

Indeed, rum was so dominant in the colonial fur trade that Iroquois called fur traders “rum carriers.”

4