So Bad a Death (8 page)

Authors: June Wright

“Blast!” I said, thinking of the meal I had prepared. “Thanks very much.”

“Just one moment, please,” said the voice hurriedly.

“Yes?”

“Mr Holland sends his compliments. Will you and Inspector Matheson dine at the Hall next week?”

The invitation took my breath away. Partly because I had presumed the voice came from Russell Street.

“This is Ames speaking from the Hall,” he announced, evidently guessing at my confusion. “You were out when Inspector Matheson rang. I promised to relay his message.” The Dower House telephone was only an extension from the Hall.

Ames? The name was faintly familiar. Oh, yes, Mr Holland's general factotum; overseer, secretary, greenkeeper, butler and what have you. Ursula Mulqueen had told me about him. His father had served the Hollands in the same capacity until his retirement to the Lodge.

“Mr Holland wants us to dine with him,” I repeated, playing for time.

“Yes, Mrs Matheson. Will Wednesday night suit you?”

I frowned at the wall.

“As far as I know now. But my husband is engaged on a case and might not be able to make it.”

There was a pause before Ames spoke. “I will inform Mr Holland. I am sure he will understand. Cocktails are served at seven, Mrs Matheson.” I heard the receiver being replaced.

I went back to the porch to bring Tony in for his meal. The phone rang again. Ames' voice was becoming familiar. This time he sounded apologetic.

“I forgot to mention, Mrs Matheson, that Mr Holland likes his guests to wear evening dress.”

“We always do,” I replied loftily, and took pleasure in ringing off first.

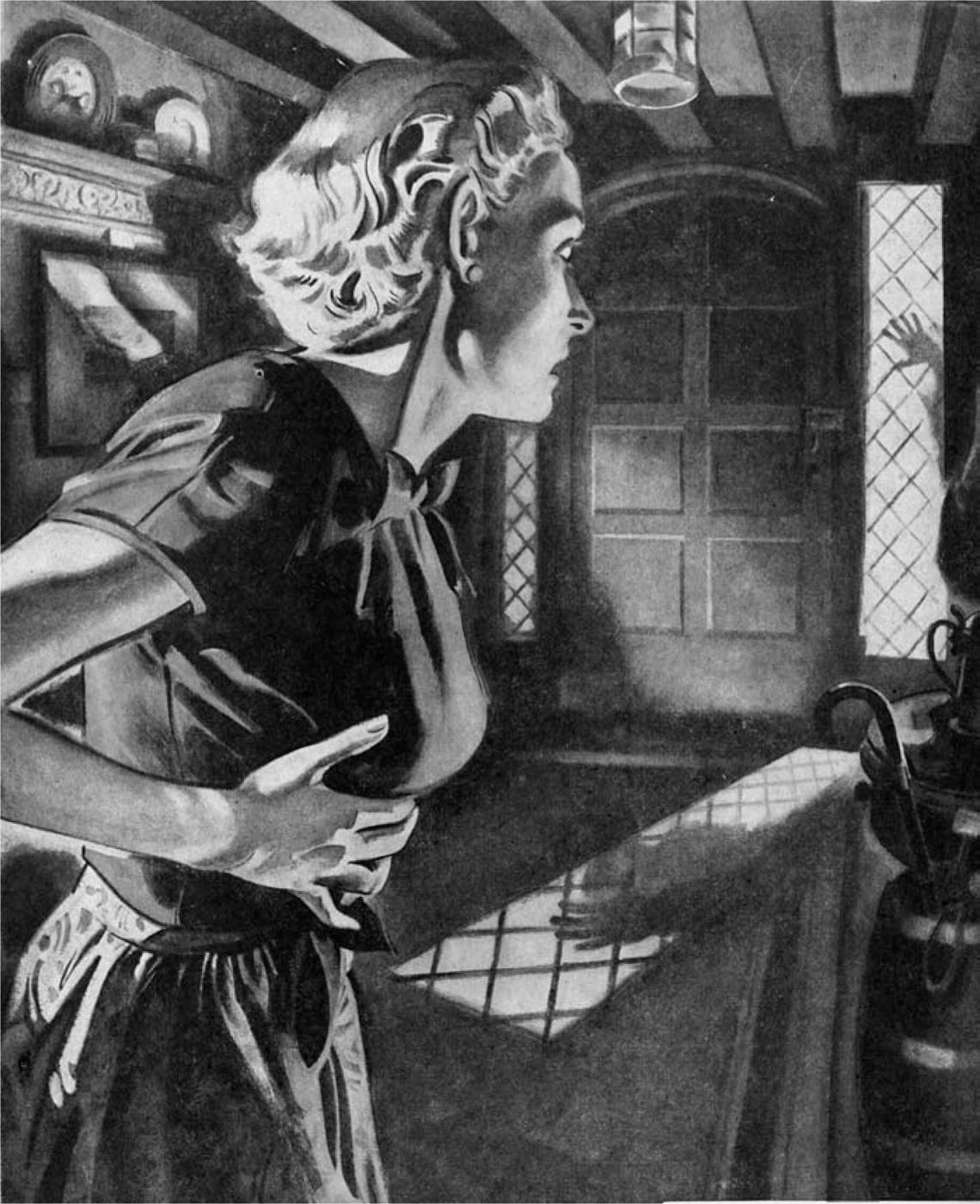

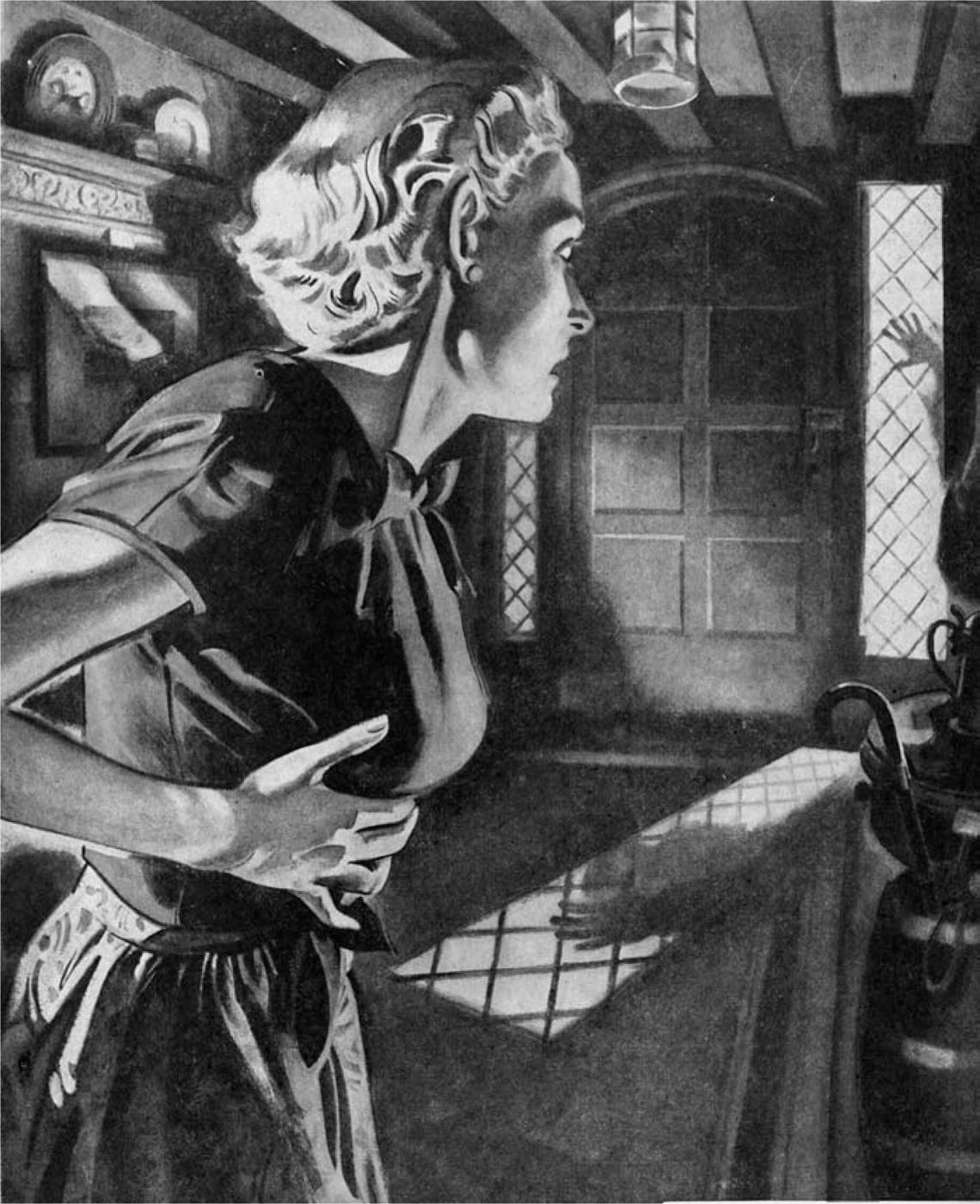

I moved about the house quickly. There was still a great deal of unpacking and arranging of furniture to be done. Ordinarily I would have welcomed the chance of John being out of the way to get it done. But that night I felt nervous. The odd creaks and reverberations, to which one becomes accustomed after a time, seemed unnatural and sinister to my ears. The silence was heavy. It made the noises sound muffled and furtive. A constant beat from the frogs in the creek and the hum of night insects reminded me of the isolated position of the Dower House. I kept Tony from bed for as long as his temper could stand it. His worn-out crying comforted me that lonely night, where it would have irritated me at another time.

In fact, I had the jitters so badly that I was compelled to put away the detective story I was reading at dinner. Even the radio was tuned into some gruesome play by Edgar Allan Poe. For a while I went bravely around the house, pulling down blinds and flooding the rooms with light. My dinner dishes were washed and dried with a clatter, but I did not open the kitchen door to put scraps in the garbage bin on the porch. An opossum in the roof, stirring before his midnight scampers, almost caused me to drop a stack of plates. I shook my fist at the ceiling, took a firm grip of myself and went into John's study to unpack a case of books.

It was this one small room, fourteen feet square, because it fitted the green carpet perfectly, which had reconciled John to the distance from town and the unreliable train service. The walls were lined with bookshelves and a gas fire had been neatly fitted opposite to the only sensible position to put a desk. This was in an alcove formed by windows facing three ways.

I crossed to them slowly and deliberately to draw the blinds, mindful that at least I had Tony for company. A mist had risen up from the creek at the back of the Dower property where the frogs still croaked incessantly. Somewhere above the mist the moon was shining, making the white trunks of the English trees in the wood slim and wraith-like, and illuminating the tower of the Hall. I forced myself to wait, watching it. I don't know why. Perhaps I was daring myself to be afraid if that mysterious light flashed from it again. I even counted up to twenty before I dropped the shade, and called myself a fool.

Kneeling beside the open case, I began to sort books. They were mainly technical tomes belonging to John, but there were a few novels of mine and a set of Shakespeare which had been a school prize. Turning over pages at random as I crouched there on the floor, something made me glance towards the door. It was closed against the draught, but I could have sworn a thread of cold air blew on my neck that I had not noticed before. Terrified, I watched the door handle, half expecting to see it slide around. I knew I was being absurd and tried to call lightly: “Is that you, darling?”

The heavy pressing silence dulled my words. Again I became conscious of the croaking of the frogs, monotonous and lonely.

“This will never do,” I told myself severely, getting up from the floor and letting the lid of the case close with a bang.

I opened the door and went into the hall. At one end the porch light shining through the narrow windows flanking the front door made a pattern on the carpet. I watched it for a moment. It was quite still. At the far end of the passage a lamp was aglow just outside Tony's room.

He was breathing quietly. The nursery was full of the warmth and companionship of him. I leaned over the cot, wishing suddenly that he was twenty years older. It would have been good to remain

there with him, but I realized that once I gave in to this state of nerves I would never be happy alone again in the Dower House. Sounds and shadows became unheard and unheeded in John's solid, satisfying presence. I left Tony's room resolved to continue with the unpacking. With one hand on the doorknob, I shot a would-be careless glance down to the front door.

That glance developed into a fascinated stare. I stood clamped to the floor, the only moving thing about me an icy drop winding its way down my spine. The pattern on the carpet just inside the front door had altered. It was blurred by the shadow of a head and shoulders. I watched it, too frightened to move. A hand was passed slowly over the leadlight.

II

The doorbell rang briefly. Who would be calling on me at this hour? Whom did I know so well in Middleburn that they would call at all?

I approached a few paces, my eye falling on a stout walking stick in the hallstand. I gripped this more to gain in moral courage than with any other design and called firmly despite my knocking knees: “Who is it?”

My breath came quickly as I waited for a reply. “My name is Mulqueen,” spoke a man's voice through the windows. “Is that Mrs Matheson? Can I come in?”

I ran down the remainder of the hall and took the chain off the door to admit the visitor. A short, ball-like man clad in a mackinaw jacket and a tweed cap stepped across the threshold. He had a pair of small twinkling eyes and a red tip to his nose.

“Hope I didn't frighten you,” he shot at me. “Heard you were all alone and thought I'd pop in to see if everything was all right.”

My relief made me garrulous.

“Not at all. Come into my husband's study. I didn't light a fire as I was by myself, but there is a gas jet. Here! Let me take your cap. And what about your jacket? It is so cold out. You might notice it more after the warm room.”

The bright eyes regarded me shrewdly.

“Windy?”

I laughed. “Very. I read too many detective stories. In here. I have been trying to forget the strange noises by unpacking.”

Ernest Mulqueen sat down on the edge of a chair and spread his hands to the fire. I found it hard to stifle a gasp at the sight of them.

He said: “Just as well you didn't see them before I introduced myself. Rabbits. I have a gin set in the wood for foxes. Go round this time every night to put the bunnies out of their agony. They will jump in, silly creatures.” He scrubbed at his bloody hands with a still bloodier handkerchief. “Humane. You probably heard me.”

I regarded him squeamishly. “I did hear some odd knocking coming from the direction of the wood. Do youâ”

“That was me. The nearest tree. Instantaneous.”

I made a mental resolve to pass by the wood in future. Ernest Mulqueen must have read my thoughts. He was a hearty, earthy little man, gifted with a keen perspicacity. Almost at once I wondered how he came to marry into the noble family of Holland, and still further how he begot a namby-pamby daughter like Ursula. She should have been a big-boned girl with useful hands: wholesome, not in the mid-Victorian sense, but rather like brown bread.

He reassured me regarding the results of his humaneness. “Quite off the beaten track. You won't see any muck.”

“Gin?” I queried, puzzled.

“A trap,” he explained. “I'm after that fox which is making a nuisance of itself on the poultry run. He's hiding out in the wood. Of all the crazy things the old man has ever done, importing a pair of foxes is the craziest. The only hunting people want to do round here is for houses.” He broke off abruptly. “How do you like this house?”

“We were lucky to get it,” I said carefully.

“Too right, you were! Never thought the old man would let it go out of the family, even after Jim's smash.”

“What happened exactly?” I asked, tilting back my chair to reach the cigarettes on John's desk. I offered them to my visitor. “Not for me, thanks. I have a pipe if you don't mind the stink. Jim? No one seems to know. Took his plane up one fine day and it fell to bits, Jim

with it. The old man was rather cut up.” He drew on his pipe and said between puffs: “Tried his hardest to blame someone other than Jim. Apple of his eye, Jim was.”

“Aren't all sons?” I said, rather sentimentally.

“Not like a Holland. You'd think they were the chosen people, the stuff that is spouted about ancestors and continuing the line. Suppose I shouldn't say that, the wife being one before I married her. But they do get your goat occasionally.”

I could not think of any suitable comment to make so I let him ramble on. He was obviously finding relief in blowing off steam after breathing in the refined air of the Hall.

“Born and bred in the country, I was. The land is the only place for me. Can't stand this polite roguery that goes under the name of business. The old man would sell us all to make a shilling, and then turn round and gas about upholding the prestige of the family. What family, I ask you. He'll pop off sooner or later and Jim has already gone. There's only that snivelling brat of Yvonne's left, and he won't make the grade, I bet.”

I started a little and my cigarette fell from my fingers. I bent to pick it up.

“Isn't Mrs Holland's son a strong child?”

“I dunno. Seems to me he's always bawling. I don't think they give the kid enough to eat. All these fancy ideas about vitamins. Lot of rot. Mind you, it's only just lately that he's got like that. He used to be a bonny little nipper.”

“Perhaps Mrs Holland should take him to a doctor,” I suggested, watching him closely.

“James doesn't believe in coddling the kid. There's some old witch in the house who used to be Jim's nurse. He swears by her.”

“What does Yvonne say?”

Ernest Mulqueen knocked out his foul-smelling dottle.

“Nothing. It's what the old man says that goes. Maybe you'll find that out yourself one day.”

He added with a trace of bitterness: “You can't fight him. He always wins. Look at me! I used to run my own place up the Riverina way. When I married the wife what happens? She develops a heart

or something and must be near dear James. Ursie must be brought up right. My farm can be run along with the rest of his property. To cut a long story short, he collars my land, puts me down here at a miserable screw and gathers in the profits.”