So Long Been Dreaming

So Long Been

DREAMING

NALO HOPKINSON & UPPINDER MEHAN eds

SO LONG BEEN

DREAMING

Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy

ARSENAL

PULP PRESS

Vancouver

SO LONG BEEN DREAMING: POSTCOLONIAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY

Stories and essays copyright © 2004 by the authors, unless otherwise indicated

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may use brief excerpts in a review, or in the case of photocopying in Canada, a license from Access Copyright.

ARSENAL PULP PRESS

#102-211 East Georgia St.

Vancouver, B.C.

Canada V6A 1Z6

www.arsenalpulp.com

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the British Columbia Arts Council for its publishing program, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program for its publishing activities.

Design by Solo

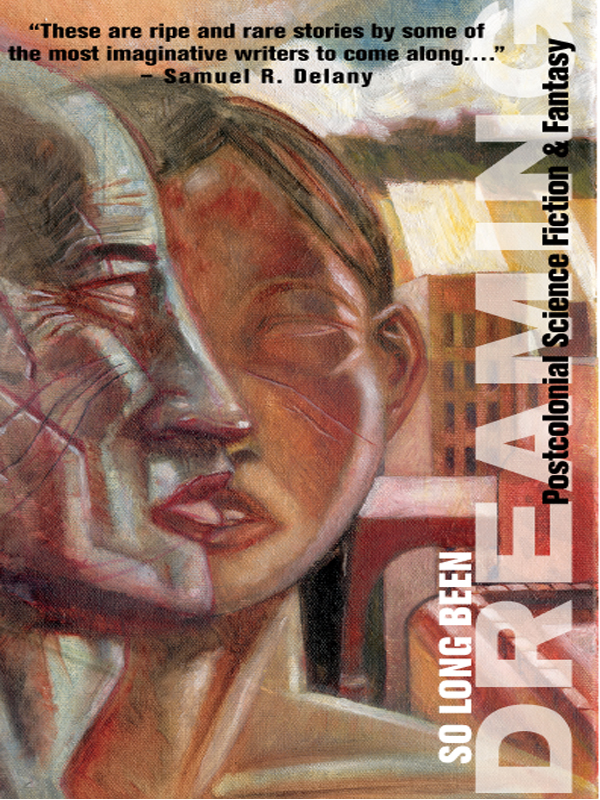

Cover illustration by Ho Che Anderson

Printed and bound in Canada

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance of characters to persons either living or deceased is purely coincidental.

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

So long been dreaming : postcolonial science fiction & fantasy / edited by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan.

ISBN 978-1-55152-158-9

eISBN 978-1-55152-316-3

1. Science fiction. 2. Fantasy fiction. 3. Developing countries – Literatures – 21st century. I. Hopkinson, Nalo II. Mehan, Uppinder, 1961-

PN6071.S33S6 2004808.83'876C2004-900676-2

Introduction

Nalo Hopkinson

Deep End

Nisi Shawl

Griots of the Galaxy

Andrea Hairston

Toot Sweet Matricia

Suzette Mayr

Rachel

Larissa Lai

Terminal Avenue

Eden Robinson

When Scarabs Multiply

Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu

Delhi

Vandana Singh

Panopte’s Eye

Tamai Kobayashi

The Grassdreaming Tree

Sheree R. Thomas

The Blue Road: A Fairy Tale

Wayde Compton

SECTION IV: ENCOUNTERS WITH THE ALIEN

The Forgotten Ones

Karin Lowachee

Native Aliens

Greg van Eekhout

Refugees

Celu Amberstone

Trade Winds

devorah major

Lingua Franca

Carole McDonnell

Out of Sync

Ven Begamudré

SECTION V: RE-IMAGINING THE PAST

The Living Roots

Opal Palmer Adisa

Journey Into the Vortex

Maya Khankhoje

Necahual

Tobias S. Buckell

Final Thoughts

Uppinder Mehan

Introduction

Nalo Hopkinson, co-editor

I met and became friends with Uppinder Mehan when he was still living in Toronto. A little later, he told me that he was about to have an essay published, entitled “The Domestication of Technology in Indian Science Fiction Short Stories” (in

Foundation: the International Review of Science Fiction

, No. 74, Autumn 1998). As a fiction writer, I myself was struggling with what seemed like the unholy marriage of race consciousness and science fiction sensibility, and I was hungry for any critical thought that might shed light on the topic. I got myself a copy of Uppinder’s essay, and there was light indeed. In fact, some of his ideas on the development of indigenous metaphors for technological progress influenced me strongly as I finished the novel

Midnight Robber

.

A friend and fellow science fiction writer, Zainab Amadahy, once introduced me to a friend of hers, a black scholar who had recently completed his PhD. We got to talking about my short story “Riding the Red,” which does a jazz riff on the folk tale of Little Red Riding Hood. He listened to my description of my story, then asked, “What do you think of Audre Lorde’s comment that massa’s tools will never dismantle massa’s house?”

I froze. Much of the folklore on which I draw is European. Even the form in which I write is European. Arguably, one of the most familiar memes of science fiction is that of going to foreign countries and colonizing the natives, and as I’ve said elsewhere, for many of us, that’s not a thrilling adventure story; it’s non-fiction, and we are on the wrong side of the strange-looking ship that appears out of nowhere. To be a person of colour writing science fiction is to be under suspicion of having internalized one’s colonization. I knew that I’d have to fight this battle at some point in my career, but I wasn’t ready. Hadn’t yet formulated my thoughts on the matter. I was still struggling to figure it all out for myself. “What do you mean?” I asked, stalling for time.

He looked at me and said (I’m paraphrasing), “We’ve been taught all our lives how superior European literature is. In our schools, it’s what we’re instructed to read, to analyze, to understand, how we’re taught to think. They gave us those tools. I think that now, they’re our tools, too.”

I found I was able to breathe again. And now I had plenty to think about. When I write science fiction and fantasy from a context of blackness and Caribbeanness, using Afro-Caribbean lore, history, and language, it should logically be no different than writing it from a Western European context: take out the Cinderella folk tale, replace it with the crab-back woman folk tale; exchange the struggle of the marginalized poor with the struggle of the racialized marginalized poor.

And yet, it’s very different. When I rewrote my story “Riding the Red” in Jamaican creole, all of a sudden I could no longer have a peasant grandmother living in a cottage in Britain’s past in the middle of the English woods; how would a Jamaican farm woman have gotten there in the seventeenth century? Not inconceivable, but I didn’t want to stop and explain the how. So I brought my Jamaican granny home. She doesn’t live in a forest; we don’t call them forests, and besides, how is she to feed herself in the middle of a forest? So now she lives on a small hand-hewed farm with the tropical bush not too far outside her front door. Little Red Riding Hood doesn’t want to attend soigné Cinderellaesque balls; come Saturday evening, she want feh go a-dance hall. And the scourge of the little girl and her granny can’t be a wolf; no such thing in Jamaica. Instead, he becomes that boogie man from Caribbean folklore, Brer Tiger. These are changes that should be superficial, but that end up giving the story a completely different feel. Even the title had to change from “Riding the Red” to “Red Rider,” a creole phrase that evoked Caribbean music and sexual innuendo. In my hands, massa’s tools don’t dismantle massa’s house – and in fact, I don’t want to destroy it so much as I want to undertake massive renovations – they build me a house of my own.

So, a little while ago, Uppinder approached me about co-editing an anthology of postcolonial science fiction short stories written exclusively by people of colour. The idea excited me. If I were to edit such an anthology on my own, I would likely have chosen to include white writers, since I feel that a dialogue about the effects of colonialism is one that white folks need to have with the rest of us, but I also understand and believe in the importance of creating defended spaces where marginalized groups of people can discuss their own marginalization. I wanted to see what would happen if we handed out massa’s tools and said, “Go on; let’s see what you build.”

What you hold in your hand is the result; stories that take the meme of colonizing the natives and, from the experience of the colonizee, critique it, pervert it, fuck with it, with irony, with anger, with humour, and also, with love and respect for the genre of science fiction that makes it possible to think about new ways of doing things.

Toronto, March 2004

The first four stories in the anthology – “Deep End” by Nisi Shawl, “Griots of the Galaxy” by Andrea Hairston, “Toot Sweet Matricia” by Suzette Mayr, and “Rachel” by Larissa Lai – explore the close connections between body and identity. In “Deep End,” a black jailed woman struggles with questions of identity and community as she hurtles towards a new planet. Hairston’s story makes literal the figure of the griot as the embodiment of communal memory. Mayr appropriates an old Irish folktale in an attempt to address her postcolonial hybrid identity. And in Lai’s “Rachel,” a replicant’s attempt to understand her implanted memories racializes that neutral but somehow always white construction, the android.

Most recently,

Nisi Shawl

’s stories have been published in Asimov’s

SF Magazine

and

Strange Horizons

; they also appear in

Mojo: Conjure Stories

and in both volumes of the groundbreaking

Dark Matter

anthology series. With her friend Cindy Ward, she teaches “Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction,” a class based on her thought-provoking essay “Transracial Writing for the Sincere.” A member of the board of the Clarion West Writers Workshop, she lives in Seattle, on a direct bus route to the beach.

Deep End

Nisi Shawl

The pool was supposed to be like freespace. Enough like it, anyway, to help Wayna acclimate to her download. She went in first thing every “morning,” as soon as Dr Ops, the ship’s mind, awakened her. Too bad it wasn’t scheduled for later; all the slow, meat-based activities afterwards were a drag.

The voices of the pool’s other occupants boomed back and forth in an odd, uncontrolled manner, steel-born echoes muffling and exposing what was said. The temperature varied irregularly, warm intake jets competing with cold currents and, Wayna suspected, illicitly released urine. Overhead lights speckled the wall, the ceiling, the water with a shifting, uneven glare.

Psyche Moth

was a prison ship. Like all those on board, Wayna was an upload of a criminal’s mind. The process of uploading her had destroyed her physical body. Punishment. Then the ship, with Wayna and 248,961 other prisoners, set off on a long voyage to another star. The prisoners cycled through consciousness: one year on, four years off. Of the eighty-seven years en route, Wayna had only lived through sixteen. More punishment, though it was unclear whether it was oblivion or the time spent in freespace that constituted the actual punishment. Or maybe the mandatory classes they took there really were intended to be rehabilitative, as Dr Ops claimed.

Now she spent most of her time as meat. When

Psyche Moth

had reached its goal and verified that the world it called Amends was colonizable, her group had been the second downloaded into empty clones, right after the trustees.

Wayna’s jaw ached. She’d been clenching it, trying to amp up her sensory inputs. She paddled toward the deep end, consciously relaxing her useless facial muscles. A trustee had told her it was typical to translocate missing controls.