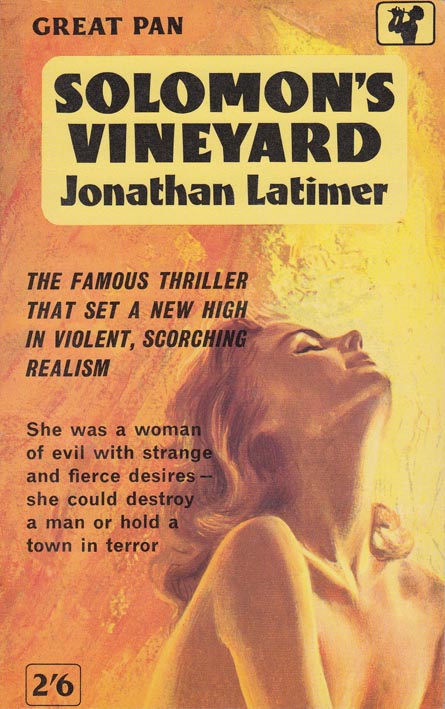

Solomon's Vineyard

Read Solomon's Vineyard Online

Authors: Jonathan Latimer

Jonathan Latimer

This page copyright © 2004 Blackmask Online.

http://www.blackmask.com

Listen. This is a wild one. Maybe the wildest yet. It's got

everything but an abortion and a tornado. I ain't saying it's true.

Neither of us, brother, is asking you to believe it. You can lug it

across to the rental library right now and tell the dame you want your

goddam nickel back. We don't care. All he

done was write it down

like I told it, and I don't guarantee nothing.

KARL CRAVEN

FROM THE way her buttocks looked under the black silk dress, I knew

she'd be good in bed. The silk was tight and under it the muscles

worked slow and easy. I saw weight there, and control, and, brother,

those are things I like in a woman. I put down my bags and went after

her along the station platform.

She walked towards-the waiting-room. She had gold-blonde hair, and

curves, and breasts the size of Cuban pineapples. Every now and then,

walking, she'd swing a hip until it looked like it was going out of

joint and then she'd throw it back in place with a snap, making the

buttocks quiver under this dress that was like black skin. I guess she

knew I was following her.

A big limousine waited beyond the magazine stand. I stood in the

shadow of an apple machine and watched her get in. Her legs were

strong, like a dancer's. I was staring at the white flesh above the

silk stocking when the chauffeur closed the door and took her bags from

a redcap and put them in front. He gave the redcap four bits and

climbed back of the wheel. She had been looking straight ahead, but

suddenly she turned to the window and smiled at me. Her smile said: We

could have fun together, big boy.

The limousine went away. I watched until it was out of sight. Some

doll) Maybe the town wouldn't be so bad after all. It was hot on the

platform and I felt sweat ooze under my arms. I showed my bags to the

redcap and called a cab. The train began to pull out of the station,

the engine throwing steam on a baggage truck. I gave the redcap two

bits and got in the cab. It had a sign saying:

Anywhere in town

—50c. The driver didn't bother to close the door.

“Where to?”

“Any aircooled hotels?”

“In this burg?” The driver snorted. “Don't make me laugh.”

“What's a good one then?”

“There's the Greenwood.” The driver turned around and squinted at me.

“Or the Arkady.”

“Which is the best?”

“The drummers use the Greenwood.”

“Take me to the Arkady.”

Hot air rose from the brick pavement on Main Street, making the

building look distorted. I saw the town was mostly built of red brick.

The pavements and the business buildings and even some of the houses

were made of red brick. I saw a cop leaning against the front of a drug

store. He had on a dirty shirt and needed a shave. Main Street was

littered with papers and trash. A Buick went through a red light by the

drug store, but the cop didn't move. There were plenty of cars parked

diagonal to the curb, but there weren't many people outdoors. It was

too hot.

We went by a movie house, turned left where it said

No Left Turn,

and climbed a hill. I saw a gulley with a shallow stream. The water

looked stagnant. In the distance there was another hill with four brick

buildings and a smaller white one near the top. There were green fields

and grape vines on the hill. The white building looked like a temple. I

pointed out the hill to the driver.

“That's Solomon's Vineyard.”

“What?”

“You heard of it,” the driver said. “A religious colony. Raise grapes

... and hell.”

He looked around to see if I liked the joke. I liked it all right. I

laughed.

“About a thousand of 'em up there. All crazy. Believe in a prophet

named Solomon.” We crossed a square with streetcar tracks and a park.

“He's dead. Died five years ago, but the damn fools're still expecting

him back.”

About five blocks from the square we came to the Arkady. It was a

rambling three-story brick building with metal fire-escapes on the

front. There were a dozen or so rocking-chairs on the porch. I saw a

sign:

Mineral Baths,

and that gave me an idea what kind of a

hotel it was. A Negro porter saw us and loafed down the steps.

“How much?” I asked the driver.

“A buck.”

“Your sign says anywhere in town for fifty cents.”

He shifted a plug of tobacco to the left side of his mouth. “Don't

always believe in signs, mister.”

He had shifty eyes and his lips were stained yellow from the tobacco.

He looked like a ball player I used to know. I got out a fifty-cent

piece and flipped it in his face. “Give the porter my bags,” I said.

He snarled and I got ready to hit him, and then his face fell apart.

He gave the bags to the Negro. There was a red mark where the coin had

caught the bridge of his nose. He bent down to pick it off the

floorboard and I went up the stairs and across the veranda and into the

lobby. The air inside stank of incense. I saw potted palms and heavy

mahogany furniture and brass spittoons. Three women were sitting by the

reception desk. The clerk was a small man with a smile—and coy brown

eyes. He had on a red necktie. I wrote Karl Craven on the register.

“Have you a reservation, Mr. Craven?” the clerk asked.

I looked at all the keys in the boxes. “What the hell would I need a

reservation for?” I asked.

He giggled. He got out a key and gave it to the Negro. “We have to

ask,” he said. “It impresses

some

people.”

I went to the elevator. The women were looking at me. One of them was

younger than the others; a pretty redhead with her skirt pulled high

over crossed legs. Her face was sullen, and when I looked at her she

stared right back at me. She had beautiful legs.

The elevator made it to the third floor and the porter led me to 317.

He put the bags down, and while he opened the windows I took a gander

at the room. There were twin beds and a big dresser with a white stain

where some gin had spilled, and a couple of big chairs. There was a

Bible and a phone book on the dresser. There was a patch in one of the

green bedspreads. By the door the rug was worn. On a table between the

beds was an old-fashioned telephone with an unpainted metal base and a

transparent celluloid mouthpiece.

The Negro finished the windows. He looked in the bathroom and the

closet. He was stalling for a tip. “Boy, who's the babe in the lobby?”

I asked him.

“The young one?”

“The redhead.”

“That's Miss Ginger. She's a friend of Mr. Pug Banta.”

I remembered the name. He was a former East St Louis gangster. Not an

important hood, though. He'd run alky and killed a couple of guys in

the old days. He was tough enough, but he never was a big shot. I

remembered he was supposed to be running a bunch of roadhouses

somewhere further west.

“And Mr. Banta wouldn't like it if I fooled around?”

“No, sir.” The Negro was positive about it. “Sure wouldn't like it.”

“Well, I got another chance,” I said. “A very swell blonde. She's got

a chauffeur.”

The Negro said: “That's the Princess.”

“The hell!” I said. “What Princess?”

“She live at the Vineyard. Head of the women there.”

“The place up on the hill?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What's your name?”

“Charles.”

“Well, Charles, what are they like up there?”

“Oh, they all very holy.”

“I couldn't call up and ask the Princess for a date?”

His eyes got big at the idea. “No, sir,” he said. “No, sir.”

I threw him a quarter, but he didn't go away.

“I can ...” he began.

“How young?”

“'Most any age.”

“I like 'em around fourteen.”

His eyes spread out. “Mister, that's jail bait in this state.”

“Well, I'll let you know,” I said.

He started to go. “Hold it,” I said. I looked in the phone book for

Mrs. Edgar Harmon's boarding-house. It was at 738 B Street. The Negro

said that was only six blocks away. “Okay,” I said.

He left. I took off my coat and the shoulder holster and my shirt.

The shoulder holster always chafed me when it was hot. I went in the

bathroom and washed my face and chest. I dried myself and put on a

clean shirt. My old one was wringing wet. Oke Johnson was living at

Mrs. Harmon's boarding-house. I decided to walk over there. He'd

written he had something. We needed something.

The clerk behind the reception desk simpered at me. He looked like a

pixie. I thought, quite a hotel; service for all. I went out. I saw A

Street to the left, and a block further along I saw B Street. I was in

the three-hundred block. The numbers went up on my right. Seven hundred

and thirty-eight was a big, red-brick house with maples growing in

front. There was a porch and stairs that needed a coat of grey paint.

Oke had picked the place, he wrote me, because he wanted to work

quietly. He was a smart Swede; the only smart one I ever saw. I went up

the stairs and pushed the doorbell.

A fat woman in a black dress with white lace on it came to the door.

There was a mole on her left cheek, just past the corner of her mouth.

She had been weeping. “Yes?” she said.

“Mr. Johnson, please.”

Her puffy eyes came open. “Are you from Mr. Jeliff?”

“No.”

“Oh, you're from the police. Come in.” She went on talking so fast I

didn't have time to say anything. “I guess you know I sent for Mr.

Jeliff. He was Mr. Johnson's only friend in town. It was funny, him not

being a butcher himself. I never knew what he did, though I will say he

had plenty of money.”

By this time I was in the house. “I'm not from the police,” I said.

“Oh,” she said. “Why do you want to see him?”

“I'm a friend. St Louis. Has anything happened to him?”

“Oh!” she said. “Oh!” She hurried up the stairs, moving fast for so

big a woman. I began to feel funny. It was one of those things you get

sometimes, premonitions, it says in the dictionary, that tell you

something is wrong. I didn't try to think what it could be; I just

waited until she came downstairs with two men. I saw they were

plain-clothes cops.

“This is him,” the woman said.

The younger of the cops got behind me so I couldn't run away. The

other, a middle-sized man with a pasty face, squinted at me.

“What do you want with Johnson?”

“I'd like to see him.”

“Why?”

“I'm a friend.”

“Yeah?”

“That's what he said,” the fat woman gasped. She was out of breath

from the stairs.

“Is he in trouble?” I asked.

The cop laughed. I didn't see what was funny. The woman began to

weep. I looked at the cop.

“He's dead,” he said, watching me. “He got knocked off this morning.”

I was half expecting it, but still it gave me a jolt. I'd had a letter

from him only two days ago. He wasn't in any trouble then.

“My God!” I said. “Who did it?”

The cop behind me spoke. “Suppose we ask you that.” His voice was

harsh.

“I didn't.” I pretended to be frightened. “I hardly knew him.”

“Yeah? Then why are you calling on him?”

“I was just looking him up. I'm from St Louis. I used to know him

there. Slightly. Very slightly. I got in this afternoon, and I didn't

know anybody else in town.”