Somebody to Love? (13 page)

About fifteen minutes into the set, I looked over at Marty and noticed that his face was decomposing. The drug was beginning to kick in, and we started giving each other goofy smiles that said, “That wasn't cocaine, was it?” The Fargodome added to the weirdness of the situation with its inverted saucer shape that positioned the audience up in the air and the performers down at the bottom. To the band, it was like being on an operating table in a surgical observation room.

I always loved Jack's bass sound, so during the beginning of his solo, when I was supposed to be playing the piano, I just stopped and turned around to face the speakers, not thinking about whether that abrupt move would mess up the continuity of the song. I'm sure each member of every sixties band has stories about drug silliness onstage, but fortunately, our audiences were usually as fucked up as we were, so they pleasantly went along with whatever was happening.

Those were the good old days.

Ah yes, children. Those were the times before everybody “became powerless and our lives became manageable.”

Before consistent togetherness became “codependent.”

Before black people started killing each other over “Who's got the music?”

Before white people discovered “politically correct.”

Before a pat on the butt became “sexual harassment.”

Before you couldn't fix your computerized life if your ass depended on it—

Newsweek,

June 2, 1997.

Of course, the “fabulous free psychedelic sixties and early seventies” were not all fun and games. Consider the following:

Young men were killing each other in a dipshit war in Vietnam.

Students were being shot to death at Kent State.

Cops were using clubs and tear gas on peace demonstrators.

Birmingham was trying to shut up black people by sending in dogs and fire hoses.

And our president, attorney general, and leading civil rights leader were all being struck by assassins' bullets.

The sixties were a time when people with electric guitars naively but nobly thought they could change the whole genetic code of aggression by writing a few good songs, and using volume to drown out the ever-present whistling arsenal.

So much for acid. It may have been illegal, but it never made me any enemies. Alcohol was the “fun” chemical that fueled most of my outbursts of congenial conversation, like the cordless mike incident at the Whitney Museum. That's the

legal

beverage that causes husbands and wives to kill each other, prisons to fill up to capacity, highway death rates to soar, six-figure missed work days, and self-inflicted hospital admissions. Without my use of alcohol, Marty Balin might not have said in an interview: “Grace? Did I sleep with her? I wouldn't even let her give me head.” God only knows what offensive behavior of mine he was reacting to. I can't remember, probably because of the alcohol. Without alcohol, I'd be richer by two million dollars that went to pay lawyer's fees. What an interesting ride it's been, folks.

I stayed away from heroin, not out of any moral or righteous decision; it just didn't look like much fun. The first person I saw nodding on the stuff was an excellent guitar player who'd come to the studio where we were recording, to visit and listen to us play. When I got there, anticipating meeting him, I found him sitting in a chair, head drooping to one side and drool trickling from his mouth. (I know you're wondering about who he was, but trust me, you wouldn't know his name even if I mentioned it.)

“What's wrong with him?” I asked one of the guys.

“He's a junkie. But he just had a fix and he'll be okay in a minute.”

“If he wants to sleep, why doesn't he go to bed?” I asked.

A grin was the answer.

I was interested in drugs as a means to enjoy or alter the

waking

state. I simply couldn't figure out why anyone would take the trouble to get the money, get the dealer, get all the paraphernalia, get sick, go into a coma—and then consider it an experience they'd want to repeat.

Monterey Pop

I

t wasn't until I heard The Beatles' album

Revolver

that I started liking their music. A friend phoned when the Mop Tops were appearing on the

Ed Sullivan Show,

and said, “Wait till you see these guys. They're wonderful!” What

I

saw was four guys in their twenties wearing matching cute outfits with matching cute hairdos, singing a too-cute song, “I Wanna Hold Your Hand.” If I had been twelve years old, they might have been impressive.

At the time, my idea of rock and roll was The Rolling Stones—craggy wiseguys playing flat-out rock with seriously offensive lyrics, each of them making their own decisions about what to wear and how to look. I loved how Jagger

defied

his audience to join in the fun. The women who were my contemporaries were either folk sopranos or blues singers, categories that didn't fit Yours Truly. Jagger's bad-boy-with-attitude persona was something I understood. I didn't copy his singing style or mannerisms, but, from watching him perform and listening to his music, I learned how to let it out and damn the censorship. Jagger and The Stones were the only element I missed at the Monterey Pop Festival.

The rest of it was perfect.

Outdoor concerts are common now, but when Monterey Pop happened, I'd never seen anything like it. Produced by Lou Adler and The Mamas and the Papas, it's the only festival I can think of that was excellent in every way.

It was June 1967. In the beautiful setting of the Carmel coast, the audience area was on a large, grassy lawn surrounded by cypress and pine trees. Unlike most summer concerts where the sun shone down mercilessly, here the big tree branches broke up the light into soft beams, making everything look like a Disney version of Sherwood Forest. In back of the trees, around the perimeter of the seating space, were about thirty small booths, individually decorated with colored silks and cottons and hand-painted banners, showing off every kind of original creation—from one-of-a-kind boots and belts to framed paintings by amateur artists. Even the stalls selling food and concert items were quaint and uninfected by corporate logos and pitchmen.

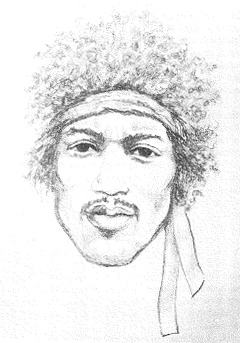

“Jimi Hendrix” (Grace Slick)

I had previously heard most of the musicians at Monterey Pop on record, but I had never actually seen them live, from Otis Redding to Ravi Shankar. The lineup boasted an all-inclusive representation of “new” music. Black, white, East, West, rock, blues, instrumental, pop, and folk—the three-day list of performers was made up of nothing but head-liners. You may have seen some of the performances in the film

Monterey Pop

on VH1 or MTV. One clip of Jefferson Airplane has the camera on Yours Truly, mouthing the lyrics of the song “Today,” but it was Marty's song and

his

voice on the soundtrack. Since I knew his phrasing, I used to just sing along while I was playing the piano, and the engineer, who knew my habits, would turn my mike off. But in the film, my lips match Marty's vocals perfectly, and it appears

I'm

the one singing. Twenty-five years ago, Marty probably wasn't too happy that no one caught the editing mistake and that my lip synching appeared in the final film version, but I'm sure he finds it mildly amusing now.

“Nobody had ever heard anything like it.” That was John Phillips talking about Jimi Hendrix's performance at Monterey. I watched him play the guitar with his teeth, use the mike stand for slide guitar, bang into the speakers for feedback, and finally set his guitar on fire with lighter fluid. None of the theatrics could overshadow his incredible musicianship. And the fabulous outfit! He wore a perfect sixties costume: Spanish hat, Mongol vest, ostrich boa, English velvet pants, silk ruffled paisley shirt, pounds of handmade jewelry, and Western boots. If any musician represented that era, it was Jimi Hendrix.

At Monterey Pop, within seventy-two hours, you could see The Who, Buffalo Springfield, The Dead, The Mamas and the Papas, Country Joe and the Fish, Big Brother with Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Laura Nyro, Ravi Shankar, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Simon and Garfunkel, Paul Butterfield, Otis Redding, Jefferson Airplane, and the band that wrote the song about it (“Monterey”), The Animals.

We all combined to create a peaceful and extraordinary offering (even the police cruisers had orchids on their antennas). And I felt lucky to be there, observing one of the great examples of human celebration.

Woodstock

O

n August 15, 1969, two years after Monterey Pop, Woodstock took center stage, both in my personal history and in collective history. It's an event that has been reported on, analyzed, sung about—even re-created twenty-five years later. Everyone has a take on that magical moment in time.

“The sun rises on a new hour of creation—we are the Woodstock nation.” Nobody and everybody said that in one way or another, from the stage, from the audience, from the heart.

“We are the Woodstock nation.”

—A

BBIE

H

OFFMAN

“Warts and all.”

—G

RACE

S

LICK

And there

were

warts. When we arrived at the concert site in upstate New York near the towns of Liberty and Woodstock, despite the initial feeling of having arrived “home,” it was clear that the as-yet-unfinished site needed a lot of work and faith to support the half million young people who'd soon be camping out there for four days.

It was construction mania. Thirty tents, fifty-foot towers for spotlights, overflowing hotels, rain-drenched muddy roads. The structure that would be a stage for forty acts was still lying around in pieces waiting be assembled. The scaffolding, sheets of plywood, and pile of two-by-fours would, in a matter of hours, become the big Erector Set platform that would support ten different bands at a time—nine waiting and one playing. It was to be a constant show from beginning to end. No intermissions. No breaks for sleeping, for peeing, for anything.

Guys in hard hats with walkie-talkies were pointing and shouting, while Chip Monck, the young lighting director, was answering five questions at once. “Please don't climb on the metal towers,” he bellowed over the PA system. “If they fall, it's fifty feet of metal crashing into five hundred people.” Big rolls of plastic sheeting were brought out to protect the electronic equipment as drenching rain suddenly and chaotically shifted everyone's plans. The skies would empty off and on throughout all the days of the concert.

Was it really going to work, this gigantic dream?

I'd been blissfully unaware of the extent of the financial fuck-ups going on around the Monterey Pop Festival, but it seemed that Airplane, Big Brother, and a couple of other bands had had to hire attorneys to find out what happened to the profits. The lawyers for the promoters said the revenue had been directed toward “charitable purposes,” but what about television syndication? No money was ever distributed to any of the bands and donations to charities were unrecorded, if they had occurred at all.

We didn't want a repeat performance of that one, so our manager, who'd learned the hard way, was determined to do it differently this time. When the negotiations for Woodstock started, Bill Thompson went to the wire in demanding that his bands be paid

before

they performed. The promoters resisted, spouting stuff about “peace and love.” But Thompson came back with how he'd be feeling a lot more peace and brotherly love

after

he'd been handed a check. It was a good move, collecting early, because we heard later that six hundred thousand dollars in bad checks eventually bounced on the bands who hadn't been paid prior to performing.

Woodstock clearly wasn't about money, since most of the bands didn't take a lot of money away from it, so what was it really about?

On the outer levels, it could be experienced as either nerve-racking chaos or joyous confusion, depending on your level of tolerance and drug ingestion. There was plenty of the latter—Owsley, the master acid chemist, was giving the stuff away, and the pot smoke could be detected for miles. In between the music, over the loudspeakers came the soothing voice of the event's bad-trip caretaker, Wavy Gravy, advising, “Don't take the brown pills,” or, “If you get confused, come to our tent and we'll help you see humor in the chaos.”

You could wear nothing or everything. Either choice of “outfit” would honor the nameless spirit. Or you could try a little of both. Adorn yourself in the full regalia of a sorcerer, roll in the mud, let the rain splash it all away, and then take all your clothes off and dance.

I wanted to be clear—light—no color. I chose white. White pants and a white leather dress with fringe that swayed when I moved, just right for the first gathering of the tribes, our first verbal declaration to the world that we were more than isolated misfits.

In the past, in all the other cities on two continents, whenever we entered a hotel, we were the minority freaks—proud of it, but still the outcasts. But when we walked into the Holiday Inn in the town of Liberty, New York, not far from the Yasgur farm, where Woodstock was held, the world of rock and roll literally filled the hotel. Wall-to-wall long-haired, loud-mouthed, laughing, screaming freaks—no longer the minority. We were, in fact, a growing representation of an inevitable shift in consciousness and ideology.