Somebody to Love? (27 page)

An Easy Ride

I

n 1979, while Skip and I were still waging our silent (and sometimes not so silent) battles with chemicals, Paul organized another version of Jefferson Starship. Minus me. The group was composed of Aynsley Dunbar on drums, Craig Chaquico on lead guitar, Pete Sears on keyboards, David Freiberg on bass, Paul on rhythm guitar, and a new lead singer, Mickey Thomas (who'd sung the hit “Fooled Around and Fell in Love”). The new group produced a successful album,

Freedom at Point Zero.

While Jefferson Starship was working on a second LP, the producer, Ron Nevison, in conjunction with Kantner, called to ask me if I'd like to come in and put down harmonies on one of the songs. The group was recording in Sausalito, just five minutes away from the house Skip and I had bought in Mill Valley, so it seemed relatively uncomplicated. No pressure: just hang out, sing a little bit, see old buddies, and get friendly with the local recording studio operation.

As we entered the eighties, long songs about revolution and chaos were mostly in the past, now the property of the Brit punks, so rather than rely on group-written material, Starship reached out to outside writers. Of course, because most of us considered ourselves songwriters, we would have preferred to have our own songs on the records. But when an outside writer provided the producers with what they thought was an excellent song, or possibly a hit, we swallowed our pride and deferred to consensus.

To give you a sense of how commercial considerations had—and

have

—taken over, consider a song I wrote in 1989, the year of the Jefferson Airplane reunion album, called “Harbor in Hong Kong,” about the initiation and success of the opium/tea trade and the eventual turnover to Communist China. It was a good song, not simple enough to be a single, however, and too anachronistic to rate as an album cut. So it wasn't used. Back in 1968, though, I would have recorded it, objections be damned, and the fact that it was quirky would have been even

more

reason to include it in the final product. But times had changed.

“You want to make strange albums with no single possibilities in the eighties? Use your own money, Grace.”

I didn't.

Eventually, the group's commercial pandering got to Paul, starting with the pimple cream sponsorship to which we'd all agreed. By that time, mounting a rock-and-roll tour took a ton of money: the trucks, lights, sets, and transportation all required big bucks. So sponsorship was necessary. I didn't really object to it, but you had to be careful who your sponsor was. Integrity nags, so I certainly wouldn't have wanted to advertise Exxon. On the other hand, Tom's of Maine toothpaste just didn't have the bucks behind it to mount a tour. So the alternatives we were left with were few. Result: this way-over-thirty band accepted pimple cream money to support touring expenses.

Adding to Paul's misery were songs of the “Baby, why don't you love me?” ilk. He just couldn't handle it, and he also resented the time limits set for the length of songs. There could be no more eleven-minute songs because Top 40 radio wouldn't play them, and the rest of the group wanted hit singles to help sell the albums and pull in the bucks.

Also driving Paul batty was the overreliance on the same formulaic song structure: verse-verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-verse-chorus-out. It simply wasn't Paul's style. His personal integrity was crashing into the desire of the rest of the group to go with the current trends.

Was he right? Sure. From where he was standing. And we thought we were busy being sensible and modern. As usual, somewhere in the middle was the truth. But Paul knew his

own

truth. He left the band in disgust, and Jefferson Starship continued as simply Starship.

The record company, on the other hand, couldn't have cared less who wrote the songs as long as they sold, so the new Starship wound up soliciting Top 40 hits from “pros” and “up-and-comers.” The multitalented Peter Wolf (no, not Faye Dunaway's ex) wrote “Sara” with Ina Wolf, Diane Warren wrote “Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now,” and Bernie Taupin, collaborating with Peter Wolf, Dennis Lambert, and Martin Page, contributed “We Built This City.” All three songs quickly went to No. 1 and ensured the group a consistent string of successful records and tours during the mid-eighties.

Left to right:

David Freiberg, Mickey Thomas, Grace Slick, Paul Kantner, and Pete Sears, smiling, sober, and selling out. (Roger Ressmeyer/© Corbis)

As fate would have it, my participation in the latter two songs with Starship led to a continuing role. Between

Welcome to the Wrecking Ball

and

Software,

two forgettable solo albums I managed to squeeze out, I was bumped up to singing duets with Starship's Mickey Thomas. That was fine with me, but Mickey had envisioned himself as commanding the spotlight (by himself) at the front of the band—until I arrived to ruin his vision. Since two of Star-ship's monster singles were our duets, it became increasingly difficult for him to make a case against pairing up with me. He was never vocal about it, but it was easy to tell that singing with the old broad clearly wasn't his idea of the ultimate rock-bank lineup.

I thought Mickey would recognize that singing duets wasn't a lifelong sentence, and that if he could put up with me for a few more albums, he'd gain the commercial clout to go out on his own and pull in the stadium crowds. But he didn't see it that way. As it turned out, neither of us mentioned our discomfort to each other, and polite acceptance lingered until 1986.

Going for the glam. (Roger Ressmeyer/© Corbis)

Left to right:

Grace Slick, Jane Fonda, and Mickey Thomas: two seconds with a hotshot. (© Steve Schapiro)

Another problem arose: Aynsley Dunbar, our new drummer, was fired, and that's how Donny Baldwin, one of my all-time favorite people, became the drummer for the rest of the Starship records.

After Paul left, I remained the last shred of the original Airplane lineup, and I was enjoying an easy ride. Skip, having recovered from the worst part of his illness, once again took on the lighting director job. With him, Donny Baldwin, Pete Sears, producer Ron Nevison, and Peter Wolf all part of the mix, I was surrounded by friends and good traveling companions. The congenial atmosphere made our pop MOR (middle of the road) music tolerable, and the three chart-toppers supported our various families of children, dogs, grandmothers, and mortgages.

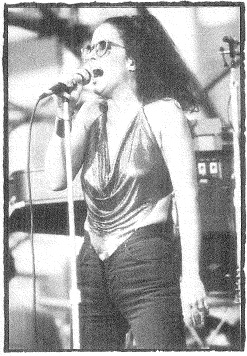

A middle-aged person on a rock-n-roll stage. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Life had become more stable—with the exception of a few unavoidable incidents that were related to celebrity. One night, I was lying awake beside a sleeping Skip, letting my mind wander, when I saw a figure appear in the darkness of our bedroom doorway. For some reason, I thought it was one of the band or crew members screwing around, so I tapped Skip on the shoulder and asked him, “Do you know who that is?”

Since my eyesight isn't as good as Skip's, I didn't see the gun in the man's hand. Skip did, however, and let out a wordless yell that was so loud and excruciating, the guy ran out of the room, down the stairs, and right through a plate-glass door, his plans thwarted by sheer decibel volume. Good old rock and roll. Caught by the police after we lodged a complaint, the screwball said that an extraterrestrial had sent him to Maria Muldaur's house to make contact. (With a gun?) The poor fool had apparently confused me with Maria Muldaur, another dark-haired singer who also lived in Mill Valley. I never did call her to find out if he'd honored

her

with his unraveled presence.

China was an easy child to love and care for, and Skip was, and still is, my “rock” and my “brother.” There were few intrusions into our much needed respite from the more exciting but ultimately ravaging celebrations of full-on drug rock. Sober, smiling, and selling out, I realized I was becoming my mother—not a bad role model, but not

me.

And yet, playing Virginia Wing was better than playing the deadly games I'd favored previously.

Unfortunately, Paul, now gone from the group, was beginning to exhibit some of his own peculiarities by compiling a collection of bad Starship reviews and jokes made at the group's expense. When Starship checked into the various hotels where it was booked, our cubbyholes would be full of these bad reviews. They arrived before we did; Paul had individually addressed them, wanting us to have something negative to think about while we were enjoying our commercial grand slam. Although some of the jokes he sent were actually funny, we recognized the gesture for what it was: an indication of how much pain he was feeling.

For me, the eighties incarnation of Starship that Paul had left felt entirely opposite from the 1969 version of Airplane. It was almost like having two different occupations. The two bands had different focuses, purposes, and conduct; one was a circus, the other a musical shopping mall. Starship was a

working

band: do the albums, do the videos, do the road trips. No drugs, no alcohol, no wild parties, and no fooling around with anyone but my husband. I drove China to and from school when I was home, did the grocery shopping, and conducted myself with uncharacteristic reserve.

Any hanging out with hotshots during the eighties happened incidentally in uneventful moments during awards ceremonies or talk shows. For instance, I met Meg Ryan in the ladies' room before an appearance on

Good Morning America,

traded snide comments about cocaine with Chevy Chase on

The Merv Griffin Show,

did a couple of Letterman stints, had my picture taken with Joe Montana at the Bay Area Music Awards, went to drug-abuse counseling with Jerry Garcia, listened to Gene Simmons of Kiss talk about his post-coital Polaroid collection, met Sting, met Phil Collins. I'd love to be able to relate something profound—or even titillating—that I took away from these encounters, but they were all of the five-minute variety without either substance or glaring impropriety.

During that time, although I

felt

pretty much okay, I was keenly aware of how strange it was to be a middle-aged person on a rock-and-roll stage.

I never thought there were corners in time till