Somebody's Heart Is Burning (8 page)

“Our grandparents knew,” she said. “To us, it is just a party.”

A man crouched on the ground, covered head to toe in white powder, wearing only a loincloth. A circle of children surrounded him. When I raised my camera, he lunged toward me, shouting.

Santana sprang into motion, pushing him back. She bellowed in Fanti until the man spun around and walked away. Then she turned to me, grinning broadly.

“He wanted you to pay him for taking his photograph.”

“All he had to do was ask.”

“He expected to frighten you into giving him too much money, but I have sent him away. I have told him that I have a strong family fetish. I said if he bothers you, I will curse his family for three generations to come.”

“I didn’t know you practiced traditional religion.”

She smiled. “Oh, sistah,” she said, “I practice everything, when it is useful.”

“I want to marry white,” Virgin Billy told me the next morning over a breakfast of bland maize porridge, called

koko

, with sugar dumped on top.

“Why?” I asked suspiciously.

“I would like to have half-caste children. I like the color.”

“So it’s an aesthetic thing?”

“Yes,” he nodded. “And I like white people. I like the way they live.”

“You mean money.”

“Not just money,” he protested. “They are educated. I would like my children to go to school in Europe, or the United States. Then they can become lawyers, or write books, or be bank managers, or artists.”

I smiled at this unusual assemblage of occupations. “Artists?” I said, “Why artists?”

“Artists are paid very well,” said Billy.

“Not in the U.S.”

“Here in Ghana they are,” he insisted. “You can make one picture, a simple picture, and sell it for 20,000 cedis. Or weave some

kente

and sell it for 8,000. Some artists own five buildings.”

“A word of advice,” I said. “If you meet an American or European woman whom you want to marry, don’t mention to her that you want to marry white. Just pretend that she, as an

individual,

is the kindest, smartest, most beautiful woman you’ve ever known in your life.”

He nodded soberly. “Thank you for these words.”

When Billy got up and brought his plate to the kitchen, Santana slid into the seat beside me.

“Sistah Korkor,” she said to me, “whatever he tells you, you must not marry this man. He hates himself, and he will hate you even more.”

“Billy?” I asked with surprise. “Why would you think that?”

“There are some men in Ghana here,” she said, “they hate themselves and love white people. But if a white woman will love them, soon she will become just like a black woman to them. I have seen this before.”

“The white man brought us civilization,” Billy told me the next afternoon as we stood side by side at the construction site, applying mortar and bricks to a growing wall.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Before the white man came, we were living in trees. We were uncivilized. Then when he came we were afraid, and we ran into the jungle.” He put down the brick he was carrying and flailed his hands in the air, imitating a frightened villager running for cover. “It is only unfortunate that we have not retained better relations with the British. Look at Ivory Coast. They are wealthier than we are, because they have kept a good relationship with the French. Kwame Nkrumah should not have thrown out the British so fast. When you leave your mother’s house, you should not shun her. You should keep good relations with her, so that you can come to her for guidance and support.”

I was so stunned that for a moment I didn’t know what to say. Ghana, formerly Gold Coast, had gained its independence from the British in 1957, making it the first sub-Saharan African nation to break free of colonialism. Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, leader of the Ghanaian independence movement, first president of the new Ghana, and an early African nationalist, was a hero here. It was he who had given present-day Ghana its name, after a prosperous West African kingdom that flourished between the fourth and eleventh centuries. I had thought Dr. Nkrumah uniformly revered. Billy was the first person in Ghana I’d heard criticize him.

“Africa has the oldest civilization on earth!” I sputtered. “Look at the ancient universities of Timbuktu! You had elaborate systems of government long before the British came and carved the place up. If people ran toward the forest when they saw white faces, they were smart to do it. Look what the whites did to this continent! Slavery! Colonization! Generations of exploitation!”

“Yes, yes,” he said dismissively, “but it was all for the best.”

“Sistah Korkor, I am not happy,” Santana told me. “I have not been happy for some six months.”

The camp was over, and I was spending a week in Apam with Santana’s family before heading north to another camp. Apam was a fishing town on the coast. Before his death, Santana’s father had owned a small fleet of boats there. As a teenager, Santana often took the bus to Accra, carrying batches of smoked fish to sell at the market. Whenever possible, she used these trips to develop her English skills. She had attended six years of school— a lot for a small-town Ghanaian woman of her generation, but not enough to satisfy her curiosity about the world. Whenever she met white people, she spoke to them. She’d heard about the voluntary association from a German woman she met on the bus.

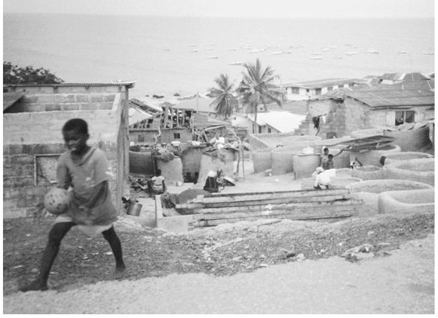

Apam had a peculiar beauty all its own—a dreamy, unruly splendor. Looking down on the town’s flat expanse from Fort Patience, the seventeenth-century Dutch fort perched on a hill just outside of town, you saw a jumbled maze of houses built of gray cement or red mud, their sloping bamboo or corrugated tin roofs reaching outward to the slate blue sea. Shabby, brightly painted wooden sailboats and rowboats were jammed together on a sandbar, which stretched like a tawny arm between the shallows. A few of the small crafts boasted outboard motors.

On the rocky coast outside of town, the ocean foamed and roiled. Pigs played in the surf, and palm trees tossed their tousled heads in the breeze like Rastas at a party. Pygmy goats not more than two feet high roamed the dusty streets, bleating. Walking through town, I was amazed by the range of the goats’ voices and by their human-sounding timbre. The kids, some with shriveled umbilical cords still hanging off their bodies, whimpered in plaintive sopranos. The nanny goats scolded in nasal altos, and the billies chimed in with gravelly bad-tempered baritones. Sometimes I’d see a mother goat toddling anxiously back and forth on her short legs, looking for her kid. The call and response between the searching mother and the lost child sounded like a musical game of Marco Polo.

A short hop from the beach was a row of dilapidated colonial mansions, replete with columns, balconies, and balustrades. Santana’s extended family shared one of these with several other families. The house was in an advanced state of decay. The floorboards were loose and rotting—you had to be careful where you stepped. Parts of the ceiling were crumbling, and a gust of wind or a heavy stomp could release a small blizzard of plaster flakes.

The outhouse in Santana’s yard was filled to the point of overflowing, and no one had gotten around to digging a new one. Every morning we trooped a few blocks to the public toilet, where we waited in line to go in. The women’s side consisted of a wooden bench with six holes in a row where women squatted, side by side, like silent crows on a line. The first time we went I lingered outside, planning to enter after everyone else had gone. But either it was rush hour or the place was the hottest ticket in town, because new people arrived as quickly as others left. I finally took a deep breath and plunged in, so to speak. As I arranged myself beside my sistahs, trying to ignore a little girl who gaped at me with unmasked fascination, I waxed philosophical. To squat next to four or five other women, each of you straining in silent (or not so silent) solidarity, is a great equalizer, a uniquely humbling experience. Imagine employer and employee perched side by side every morning before work, I mused. Wouldn’t that go a distance toward breaking down hierarchy? Or world leaders, before they go into a conference room to decide their country’s fates. Every president and prime minister, I decided, should have to try this at least once.

On my second morning in Apam, after returning from these rather chastening ablutions, Santana and I stood on the sagging upper porch of her family’s home, talking. Stacks of tires, piles of wood, and crumbling cement blocks were strewn about the yard below. The scene was a kaleidoscope of motion: children chasing a ball, goats chasing the children, women stirring pots of steaming mush. Two men played cards while others stood around in a circle, drinking and offering advice. Groups shifted and reshuffled as people came and went, walking or pedaling their wide-wheeled bicycles, balancing things on their heads. At the far end of the yard, the words “Cry Your Own Cry” were painted in bright blue letters on a boarded-up shack. Beyond the yard, corrugated tin roofs stretched a few hundred yards to the cape, where the shaggy-headed palm trees leaned toward the sea.

As Santana and I talked, smells of smoking fish and roasting corn wafted up, while shouts, cries, laughter, and the staticky pulse of a radio mingled in our ears. A big-bellied, thin-limbed child in underwear sauntered barefoot across the yard, eating from a can. She looked up at us and shouted

“obroni”

fifteen or twenty times, until I waved to her and called out “Hello!” Satisfied, she continued her stroll.

“Sistah Korkor,” Santana was tapping my arm. “Did you hear what I said? I said I have not been happy for some six months.”

“What? Why?”

“My man, he has left. He has gone to Italy ten months ago. Then, some six months ago, he has sent a cassette to his parents, and he has told them that I should find a husband. He calls Ghana women a natural resource. Himself, he will find a more costly woman. A Europe woman. Because I have not traveled, I am worth nothing. A natural resource only, like water, everywhere, cheap. Because I have stayed in Ghana here.”