Southern Storm (49 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

Continued the president: “The most remarkable feature in the military operations of the year is General Sherman’s attempted march of three hundred miles directly through the insurgent region. It tends to show a great increase in our relative strength that our General-in-Chief [Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant] should feel able to confront and hold in check every active force of the enemy, and yet to detach a well-appointed large army to move on such an expedition. The result not yet being known, conjecture in regard to it is not here indulged.”

As he often did, Lincoln masked his anxieties with humor. It was in this period, when he had a meeting with the Pennsylvania politician and publisher A. K. McClure, that Lincoln asked if the newsman would like to know Sherman’s whereabouts. When McClure eagerly said that he would very much want to know, Lincoln replied: “Well I’ll be hanged if I wouldn’t myself.”

Lincoln followed his State of the Union message with a short speech this evening from the White House in response to a band concert given in his honor. “I have no good news to tell you, and yet I have no bad news to tell,” Lincoln said. “The most interesting news we now have is from Sherman. We all know where he went in at, but I can’t tell where he will come out of.” Drafted but cut from his annual message was an attempt to lower expectations about the operation and its leader: “We must conclude that he feels our cause could, if need be, survive the loss of the whole detached force; while, by the risk, he takes a chance for the great advantages which would follow success.” For the crowd gathered at the White House, Lincoln chose to end his remarks by calling for three cheers for “Gen. Sherman and the army.”

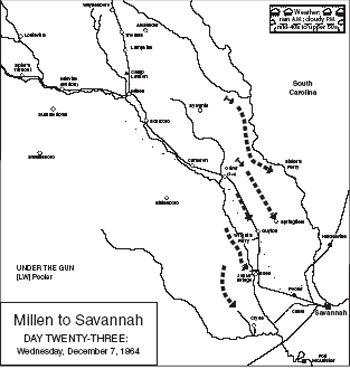

W

EDNESDAY

, D

ECEMBER

7, 1864

Left Wing

Heeding General Bragg’s admonition to press the enemy’s forces nearest the Savannah River and South Carolina, Major General Wheeler renewed his campaign of harassment aimed at the Federal Fourteenth Corps. His troopers ran up against Kilpatrick’s Second Brigade, which absorbed much of their attention during the day. There was a short but sharp skirmish first thing in the morning, followed by a larger-scale scrap late in the afternoon. In the latter, the Union riders were struck as they were feeling their way across a stream and threading gingerly through a swamp.

The afternoon fight began when Wheeler and his escort ventured too near the Federal rear guard—the 9th Michigan Cavalry—which reacted by charging the enemy party. Wheeler’s group retreated to the Rebel main body, which returned the compliment by driving the Michigan men back to their fully alerted reserve, the 9th Ohio Cavalry. For the next few minutes charge was met by countercharge as small groups of riders engaged in briefly violent combat to the accompaniment of shouts, screams, and the crack of pistols firing. One officer in the 9th Ohio Cavalry recalled the events in broken fragments—a lazy column of march suddenly transformed by shouted orders to form a line of battle, followed by the breathless command: “Draw saber, forward charge!” A Tennessean with Wheeler long remembered the civilian they had along as a local guide, an embittered old man whose property had been wrecked by marauding Yankees. Caught in the whirl of the fight, the noncombatant used both barrels of his shotgun to bring down two of the enemy, one of them a young officer. “He is very proud of his feat,” wrote the Tennessee trooper, “and feels that he had taken partial satisfaction for the burning of his house and turning his family out of shelter.”

During the engagement Wheeler’s men put enough pressure on the Union troopers that they called for infantry help. The added heft proved more than enough to squelch the fighting. Wheeler’s losses were eleven killed, wounded, or missing, while the two Federal cavalry regiments suffered thirteen casualties. The Union officer felled in this affair was the “gallant” Captain Frederick S. Ladd. For all the sound and fury, the effect on today’s movements by the Fourteenth Corps was negligible.

Far more bothersome for the foot soldiers were the swamps and occasional stretches choked by chopped timber. A Wisconsin soldier recalled how he and his comrades, after one swampy section, were “bespattered with mud from heels to crown.” The officer commanding the leading Fourteenth Corps division reported that the roadway was “badly obstructed by fallen trees, but by heavy details removed them, causing but little delay.”

A few of those marching in Baird’s division, still traveling last in line, worried about rumors that Braxton Bragg, with 10,000 soldiers from the Augusta garrison, was driving hard on their heels. It probably wasn’t a coincidence that when the division bivouacked for the night,

extra details were assigned to erect defensive barricades. The head of the Fourteenth Corps column settled in about two miles shy of Ebenezer Creek, where, scouts reported, the bridge had been destroyed. Poor staff work had allowed the pontoniers of the 58th Indiana to make their camp before it was realized that their talents would be needed. “We were aroused at 11:30 [

P.M

.] and ordered to ‘fall in,’” groused one engineer. “Four Companies were sent to Ebenezer Creek to make a bridge.”

There was emotion in the ranks of the 87th Indiana this night regarding the noncombat death of a popular soldier, Sergeant Kline Wilson. A friend who sat with him just before he died asked if he had any special message for his parents. “He said he was too weak to talk but to say to his father that he died in a good cause.” In a letter to the sergeant’s hometown newspaper, the friend wrote that “Sergt. Wilson was a brave, good soldier and his loss is deeply regretted by the officers and soldiers of his regiment, and especially of his own company.”

Marching parallel to the south of the Fourteenth Corps, the three divisions of the Twentieth encountered some especially bad sections of ground. A Michigan foot soldier complained that “in places [the swamp] was almost impassible.” In the Second Division, one brigade commander had to assign every man to be “distributed along the [wagon] train,” where they “rendered material assistance in pushing them along.” An Ohio infantryman, who termed the swampy surface “quicksand,” noted that “many teams [were] getting [stuck] fast.” It had rained off and on throughout the morning and as a result, attested a Wisconsin man, “we had to pry and pull whip & shout, to extricate the wagons…sunk to the axles in the soft quicksand.” Along one mucky patch, a New Jersey officer was struck by the sight of forty or fifty wagons “looking like so many stranded ships, stuck to their beds in the mud, with their mules resting quietly.”

For the Twentieth Corps soldiers this day’s big distraction came when they passed through the small town of Springfield, which one Illinois soldier described as “a poor looking distracted, woe begone place.” An officer in a companion regiment recollected “white flags flying at all inhabited houses.” Once they entered the town, a few of the boys discovered the pleasant charms of its female residents. A soldier in the 102nd Illinois had to laugh at the citizens who remained safe and unmolested in their houses, while having to helplessly watch

as the inquisitive Yankees found all their outdoor hiding places. “An almost endless variety of articles have been exhumed,” chuckled the infantryman. “Some are bringing any clothing, others blankets, others fine dishes, silver spoons, etc. One man has just passed us dressed as a lady, only his toilet was rather rudely made.”

For one little girl in the path of Sherman’s men, the impressions of this day stayed with her. The enemy’s approach triggered a variety of responses from her neighbors; some tried to hide their valuables, while others seemed resigned to whatever would happen. “All were in a wild state of expectancy, moving hither and thither, knowing not what was best to do,” she recalled years later. The Yankees at last arrived with the suddenness of a thunderstorm. “In a few minutes the broad grounds were literally alive with soldiers—rushing in all directions like wild Comanche Indians,” she remembered. “Parties searching through the house from garret to cellar, in every niche and corner, through drawers, closets, trunks, wardrobes, and even under beds, taking everything of any value. Outside the house, the burning of fencing and outbuildings, and the firing of guns and pistols, slaying of cows, calves, hogs, pigs, chickens, and turkeys, while others were robbing the smokehouse, dairy, syrup house and store room.”

Right Wing

Assigned to follow the Central of Georgia Railroad tracks and river road along the Ogeechee River’s east bank, the Seventeenth Corps encountered both swamps and roadblocks. A member of the 11th Illinois remembered it as “a very wet swampy country,” while another in the regiment wrote that they “had to build four or five small bridges, and also had to do some corduroy work.” “Stopped often and long while the roads are cleared of trees etc felled by the rebels,” added a man in the 20th Illinois.

The tougher traveling and diminishing prospects of locating adequate forage for the animals led to another culling of the herds. A diarist in the 12th Wisconsin noted the shooting of 100 horses and mules this day; another in the 16th Wisconsin added 200 to the sum, while a third, in the 64th Illinois, estimated the entire number of unfit animals dispatched at “about 2,000.”

The leading elements of the Seventeenth Corps camped around Station No. 3, Guyton, near where Sherman set his headquarters for the night. During the ride from Station No. 4½, Oliver, Major Hitchcock had been both sobered and amused. One of the first sights to meet his gaze this morning was a roadside burial detail setting to rest “some poor fellow’s remains…. Perhaps by some once happy fireside his place is now empty forever, and loving eyes will look vainly for his return.” The diversion was provided at midday, when the General took lunch at the Elkins residence. The matron of the house, “a regular Georgia woman,” admitted to Hitchcock that she took snuff and let her children eat clay.

Mrs. Elkins hoped that Sherman would find Savannah undefended, but he thought otherwise. “McLaws’ division was falling back before us,” he reflected, “and we occasionally picked up a few of his men as prisoners, who insisted that we would meet with strong opposition at Savannah.” When he sent Major General Slocum his movement objectives for the next few days, Sherman added the thought: “We hear that the enemy is fortifying in a semi-circle around and about four miles from Savannah.” Some of the General’s concerns percolated to his staff, so that his principal telegrapher observed today that “indications now point to a fearful & determined battle to make that harbor a base.”

It speaks to the flexibility of Sherman’s troop arrangements that while fully three-fourths of his force did little this day but march and change camps, the remainder executed several offensive missions. Yesterday the Fifteenth Corps had secured one Ogeechee River crossing at Wright’s Bridge and positioned itself near another (Jenks’ Bridge). Today the Fifteenth Corps exploited the first and forced the second.

At Wright’s Bridge, below Guyton, Colonel James A. Williamson took his all-Iowa brigade over the rebuilt span, crossed to the river’s east bank, advanced to the railroad, and turned south. The Union officer was taking no chances. “All the way down the Ogeechee we kept out flankers and skirmishers in front,” recollected a member of the 4th Regiment. This action got under way about midday. Farther south, midwesterners from Brigadier General Elliott W. Rice’s brigade (Brigadier General John M. Corse’s division) mounted a successful crossing at Jenks’ Bridge.

It was no casual operation. A slight enemy force held the opposite

bank, and the old bridge was unusable, necessitating a pontoon. The call went back to Wright’s Bridge for the 1st Missouri Engineers to come forward. The pontoniers arrived at 10:30

A.M

., and their presence triggered the action’s first phase. Under a covering fire of musketry and artillery, the engineers pushed their pontoon boats into the river to ferry several companies of the 2nd Iowa to the east bank, where they engaged the Rebels, then established a security perimeter.

Now the engineers were able to use their canvas boats for the purpose they had been designed; by 1:00

P.M

. the military bridge was carrying traffic. The rest of Rice’s brigade trouped over, with the 2nd Iowa covering the front. One of those soldiers in the advance recalled marching “about ½ mile over 5 or 6 [foot] bridges which the planks had been taken off so that we had to cross on the timbers and then deployed and advanced through the swamp knee deep in water for about 1½ miles when we came onto dry land.” Here the Rebels had concentrated to impede the advance, positioning themselves behind a rail barricade.

The 7th Iowa supported the 2nd, which attacked in open skirmishing order. A soldier in the regiment recollected having to “charge over an open field of several rods in extent. We did not wait for a second volley, but got to the barricade before they could reload and 19 prisoners were taken, and the company hurried after the rest of them.” According to this soldier, both generals Howard and Corse were on hand, the latter applauding them and exclaiming: “Brave boys, brave boys; never saw such brave boys.”