Spain (14 page)

Authors: Jan Morris

It is especially in the interior of Spain that the faith still rings true, for though Christianity is more ebullient in the south, the stern landscapes of the tableland are like sounding-boards for the spirit. Here, though your voice often falls flat upon a dry soil, or is whisked away by the bitter wind, ideas seem to echo and expand, visions form in the great distances, and man, all alone in the emptiness, seems only the agent of some much greater Power. No wonder the Spaniards, at once oppressed and elevated by the character of the place, have built upon this plateau some of the grandest of all human artifacts, the cities of the centre. They are grand not so much as collections of treasures, or gatherings of people, but as things in their own right: all different, all indeed unique, all instantly recognizable for their own savour and design, but all touched by this same resonance of setting, and thus, one feels, by something nobler still. Let us visit four of them now, and see how powerfully this combination of variety and inner cohesion contributes to the presence of Spain.

Salamanca, on the western edge of the

meseta

, is made of sandstone. One does not often specify the raw material of a city, but Spain likes to be explicit: Santiago is granite, Salamanca is

sandstone. She is the calmest of the famous cities of the tableland, set more tranquilly than most beside the River Tormes, insulated by age and culture against the fierce intensity of the country. Salamanca is above all a university cityââMother of the Virtues, the Sciences, and the Arts'âand though her scholarship has long been shrivelled, her colleges decimated in war or emasculated by autocracy, still she has the special poise that marks a place both learned and long admired.

You approach her, if you come the right way, by foot across a fine Roman bridge, and this in itself is a kind of sedative. The bridge is old, stout, and weather-beaten; the river below is wide and steady; groves of larches and poplars line the banks; and if you pause for a moment at the alcove in the middle, you will find that life around you seems wonderfully simple and assured, as though the big trucks pounding along the ring road are only some transient phenomenon from another civilization. In the thicket immediately below the bridge, perhaps, a solitary student is deep in his book at a trestle table, supported by a bottle of pop from the shanty-café along the path, and inspired by flamenco music from the radio beneath his chair. Downstream the bourgeoisie washes its cars in the river water. Across the river a small boy canters around on a pony. A mill-wheel turns at the weir upstream; sheep graze the fields beyond; in the shallows an elderly beachcomber is prodding the mud with a stick.

Raise your eyes only a little, and there above you, scarcely a stone's throw away, stand the two cathedrals of Salamancaâso close is the Spanish country to the Spanish town, so free from peevish suburbs are these old cities of the interior. It is rather like entering Oxford, say, in the Middle Ages. The city is the heart and the brain of its surrounding countryside, so dominant that the olive trees themselves seem to incline their fruit towards its market, and the mules and asses pace instinctively in its direction. Yet the physical break is instant, and complete. One side of the river is the country, the other side is the city, and there is no straggle to blur the distinction.

Almost immediately, too, the meaning of Salamanca becomes apparent, and you seem to know by the very cut or stance of the

place chat this is a city of scholars. Here is the old courtyard of the university, where generations of students have written their names in flowery red ochre; and here are bookshops, those rarities of contemporary Spain, heavily disguised with magazine racks and picture postcards, but still recognizably university shops; and here is the great mediaeval lecture-room of Luis de León, still precisely as he knew it, still bare and cold and dedicated, with his canopied chair just as it was when, reappearing in it after four years in the cells of the Inquisition, he began his lecture with the words â

Dicebamus

hesterna

die

â¦'ââAs we were saying yesterday â¦'

Salamanca University was founded in the thirteenth century, and for four hundred years was one of the power-houses of European thought. Columbus's schemes of exploration were submitted to the judgement of its professors. The Council of Trent was a product of its thinking. The concept of international law was virtually its invention. The first universities of the New World, in Mexico and Peru, were based upon its statutes. It was while serving as Professor of Greek at Salamanca that Miguel de Unamuno, driven out of his mind by the atrocities of the Spanish Civil War, rushed into the street one day shouting curses on his country, later to die of grief.

Around this institution, over the centuries, a noble group of buildings arose, and stands there still in golden splendour. The gorgeous plateresque façade of the Patio de las Escuelas, with its dizzy elaborations, its busts of Ferdinand and Isabel, and its lofty inscriptionââThe King and Queen to the University and the University to the King and Queen'âis a reminder of the importance of this place to the State, the Crown and the Church throughout the grand epoch of Spanish history. The New Cathedral, pompous and commanding, was opened in 1560 to express the grandeur of a university that then boasted twenty-four constituent colleges, six thousand students, and sixty professors of unsurpassed eminence. One of the most delightful buildings in Spain is the House of the Shells, built at the end of the fifteenth century for a well-known Salamanca sage, and covered all over with chiselled scallops. And nothing in Europe better expresses a kind of academic festiveness than the celebrated Plaza Mayor, the drawing-

room of Salamanca: its arcaded square is gracefully symmetrical, its colours are gay without being frivolous, its manner is distinguished without being highbrow, and among the medallions of famous Spaniards that decorate its façade there have been left, with a proper donnish foresight, plenty of spaces for heroes yet to come.

It is a lovely city, but like many lovely Spanish things, it is sad. Its glories are dormant. Its university, once the third in Europe, is now classed as the seventh in Spain, and seems to have no life in it. Few outrageous student rebels sprawl in the cafés of the Plaza Mayor, no dazzling philosophical theories are emerging from these libraries and lecture-rooms. Expect no fire from Salamanca. The Inquisition dampened her first, and in our own time Franco's narrow notions fatally circumscribed her. The genius of this tableland is not friendly to liberty of thought: and just as Spain herself is only now headily experimenting with the freedom of ideas, so it will be a long time, I fear, before Salamanca rejoins the roster of Europe's intellectual vanguard.

There is sadness too in Avila, though of a different kind. This is a soldier's city, cap-Ã -pie, and when you approach it from the west over the rolling plateau almost all you see is its famous wall: a mile and a half of castellated granite, with eighty-eight round towers and ten forbidding gates. It looks brand new, so perfect is its preservation, and seems less like an inanimate rampart than a bivouac of men-at-arms, their helmeted front surveying the meseta, their plated rear guarding some glowing treasure within. It looks like an encampment of Crusaders on the flank of an Eastern hill: a city in laager, four thousand feet up and very chilly, with the smoke rising up behind the walls where the field kitchens are at work.

But inside those watchful ranks, no treasure exists. Avila is like an aged nut, whose shell is hard and shiny still, but whose kernel has long since shrivelled. Her main gate is by the mottled cathedral, whose apse protrudes into the wall itself, and around whose courtyard a dozen comical lionsâthe only light relief in Avilaâhold up an iron chain, their rumps protruding bawdily over the

columns that support them. At first the shell feels full enough, as you wander among the mesh of mediaeval streets inside, through the arcades of the central plaza, and down the hill past the barracks; but presently the streets seem to peter out, the passers-by are scarcer, there are no more shops, the churches tend to stand alone in piles of rubble, and the little city becomes a kind of wasteland, like a bomb-site within the walls, several centuries after the explosion.

Avila was always a mystic city, but this wasted presence gives her a gone-away feeling. The snow-capped sierra stares down at her, the plain around seems always to be looking in her direction, the little River Adaja runs hopefully past her walls; but when you knock ather gate, there is nobody homeâand even those knights-at-arms turn out to be made of stone, and are floodlit on festival days. The life of the city has escaped the ramparts, and settled among the shops and cafés of the modern town outside; and from there, sitting with an omelette at a restaurant table, or wandering among the country buses, you may look up at the Gate of Alcazar and the city walls, and think how false, indeed how slightly ludicrous, a defensive posture can look when there is nothing at all to defend.

So emaciated does the old part of Avila feel today that sometimes it is difficult to imagine how virile she must have been in her palmy days. Was it really here that St. Theresa was born, that most robust of mystics, whose very visions were adventure stories, who jogged all over Spain in a mule wagon, and who did not even scruple to answer back Our Lord? (âThat's how I treat My friends,' she once heard a divine voice remark, when she was complaining about a flooded river crossing, and unperturbed she retorted: âYes, and that's why You have so few!') Was it really in this pale outpost of tourism that young Prince Juan, only son of the Catholic Monarchs, was trained to rule the earth's greatest empireâonly to die before his parents, and thus pass the crown to the house of Austria, to Philip II and his successors of the Escorial? Was it really in Avila, this city without a bookshop, that the great Bishop Alfonso de Madrigal, the Solomon of his time, wrote his three sheets of profound prose every day of his

lifeâto be immortalized in the end by an alabaster figure in the cathedral that shows him halfway through his second page of the day? Was it here in Avila that the martyr St. Vincent, having stamped upon an altar of Jupiter, was beheaded on a rock with his two loyal sisters?

It all feels so remote, so long ago, so out of character: in the Civil War, the last great historical event in which Spain played a part, Avila fell bloodlessly to the Nationalists, and never there-after heard a shot fired in anger. For me she is like a superb plaster cast of a city, all hollow. There is only one place in Avila in which the pungency of the past really seems to linger, and that is the crypt of the Church of San Vicente, just outside the walls on the eastern side. Here you may see the very rock on which that family of martyrs died, and beside it in the wall there is a small sinister hole. On October 27, 303, St. Vincent was executed, and his body was thrown to the dogs who prowled and yapped about the rock. A passing Jew paused to make fun of the corpse, but instantly there flew out of that small hole in the rock face an angry serpent, which threw itself upon the Hebrew and frightened him away. This episode was gratefully remembered by the Christians. For several centuries it was the custom of the people of Avila, when they wished to take an oath, to crowd down the steps of the crypt of San Vicente, and place their hands in that orifice as they swore; and to this day it is easy to see them down there in the dark, beside that rough old rockâawestruck peasant faces, queer hats and thonged sandals, a smell of must, earth, and garlic, a friar to supervise the solemnities and the slow words of the oath echoing among the shadows.

The Jew was so glad to escape with his life that it was he who built the church upstairs, and an inscription beside his tomb in the west transept tells the tale. As for the serpent, when Bishop Vilches took a false oath at the hole in 1456, out it popped again and stung him.

A world away is Segovia, and yet she stands only forty miles to the north-east, in the lee of the same mountains. If Avila is only a shell, Segovia is all kernel: she feels the most complete and close-

knit of the Castilian cities, as though all her organs are well nourished, and nothing is atrophied. The gastronomic speciality of Avila is a little sweet cake made by nuns; but the speciality of Segovia is roast suckling pig, swimming in fat and fit for conquerors.

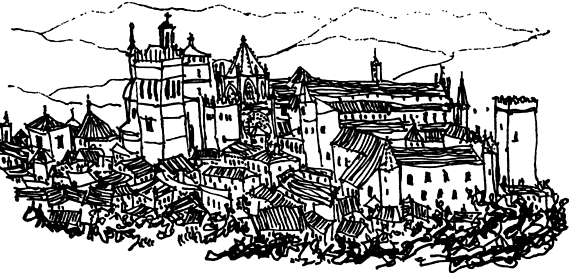

Segovia is the most beautifully organized of cities. She is a planner's dream. She lies along an elongated rocky knoll, with the sparse little River Clamores on the south side, and the more affluent Eresma to the north, and to get the hang of her you should first walk up to the little Calvary which stands, lonely and suggestive, on a hillock beside the Avila road. From there you can see the whole city in silhouette, and grasp its equilibrium. Very early in the morning is the best time, for then, when the sun rises over the plateau, and the city is suddenly illuminated in red, it loses two of its three dimensions, and looks like a marvellous cut-out across the valley. In the centre stands the tall tower of the cathedral, the last of the Gothic fanes of Spain. To the left there rise the romantic pinnacles of the Alcazar, most of it a nineteenth-century structure in the Rhineland manner, all turrets, conical towers, and troubadour windows, properly poised above a precipice (down which a fourteenth-century nanny, when she inadvertently dropped the baby, instantly threw herself too). And at the other end, forming a tremendous muscular foil to this fantasy, there strides across a declivity the great Roman aqueduct of Segovia, looking from this distance so powerful and ageless that it might actually be a strut to hold the hill up. Between these three bold cornerpostsâfortress, church, and aqueductâSegovia has filled herself in with a tight, steep, higgledy-piggledy network of streets, sprinkled with lesser towers, relieved by many squares, and bounded by a city wall which is often blended with houses too, and looks, from your brightening Calvary, rather like the flank of a great ship. She seems, indeed, to sail across her landscape. She looks like a fine old clipper ship, there in the morning sun, full-rigged, full-blown, ship-shape and Bristol-fashion.