Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere (12 page)

Read Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

Back on the tabletop, Harvey lay on his back, kicking weakly at the air. “Strike, man, strike!” he croaked.

Keeping the spellbook under her arm so that both her hands were free, Olive pried the remaining hand from Harvey’s neck and flung it down on the scrapbook. The hand stilled. It ran its fingertips over the scrapbook’s worn pages. The left hand, which had clambered up the table leg, poked at the scrapbook from the other side.

Olive turned back to the spellbook. It was still safe under her arm, its cover gleaming as softly as silk. “Get us out, Harvey,” Olive ordered.

Harvey gave his head a dizzy shake, waited for Olive to grasp his tail, and stumbled back out into the attic.

Safely outside the painting, Olive glanced up at the easel. Inside the canvas, both long, bony hands had curled around the open scrapbook in the very position they had held before. She pressed the heavy spellbook tight to her chest. Her heart pounded against its cover like a fist knocking on a door.

“All right, Sir Walter,” she whispered to the cat panting on the floor beside her. “Now let’s get out of here.”

11

I

N THE CORNER of the attic, the little candle had sputtered down to a nub. Olive hurried across the floor to pick it up. By its light, she got her first good look at the McMartins’ book of spells.

N THE CORNER of the attic, the little candle had sputtered down to a nub. Olive hurried across the floor to pick it up. By its light, she got her first good look at the McMartins’ book of spells.

Its leather cover was worn to rich amber. It was covered with bumps and dimples in places, but was as smooth as glass in others—perhaps where hundreds of years of hands had rubbed it. Ancient embossing flickered here and there on its surface, like fine threads sewn into the leather. Olive was so enthralled that she almost stepped on Harvey, who was waiting for her at the top of the stairs.

“Hey, Olive,” he said, sidling out of the way, “before we leave, would you . . . would you cover up that painting again?”

Olive glanced back up at the unfinished canvas. The slick sheen of the paint rippled in the candlelight. Aldous’s disembodied hands clutched the scrapbook. She hurried to smooth the dusty cloth back into place. The painting disappeared like a stage between a pair of closing curtains.

Harvey didn’t speak as they padded down the stairs and back out through the painted arch. He was silent in the pink room, silent in the hallway, and silent in the bathroom, where Olive stopped to leave the dying candle, freeing both hands to clasp the book against her body.

Even when they got back to Olive’s bedroom, Harvey didn’t say a thing. In the doorway, he made an odd little throat-clearing sound before darting off down the hall, but Olive was too preoccupied with the book to notice. She had the McMartins’ spellbook in her hands. Every other thought simply floated away, like bits of fuzz in front of an electric fan.

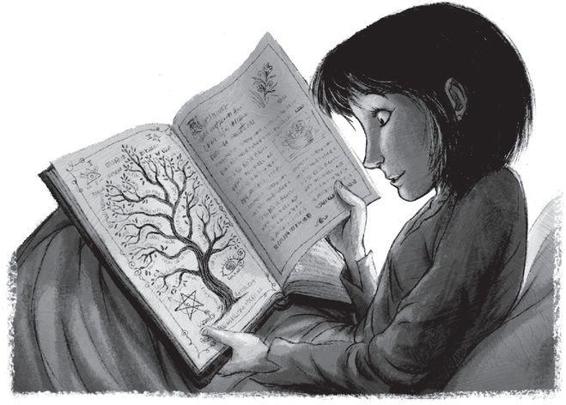

She slid into her bed, flicked on the tiny reading lamp, and tilted the book up against her knees. It was heavy and almost as wide as Olive’s body, but it nestled comfortably in her lap. Horatio and Leopold never nestled that way. Harvey was more likely to joust with a mailbox than to curl up in her lap, even if it meant giving himself a minor concussion in the process.

Gently, Olive stroked the worn leather cover, and the book seemed to glisten under her fingertips. Then, as she watched, the glinting spots carved into the leather shifted into a familiar shape—a shape so worn and so ornate with its swirls and curlicues and spots of flaking gold that she hadn’t recognized it before. It was the letter

M

.

M

.

Olive wiggled her toes beneath the sheets. She felt as if she were about to unwrap a pile of birthday presents, but with the excitement multiplied by a hundred. There wouldn’t be any lumpy sweaters, confusingly complicated calculators, or math games with names like Let’s Have Sum Fun! inside of

this

surprise.

this

surprise.

She took a deep breath, making the moment last. Then she lifted the cover and opened the book.

On the thick yellow frontispiece was a sketch of a tall, nearly leafless tree, done in strokes of dark blue ink. The tree’s trunk was thick and crooked, dividing into a tangle of branches and twigs, all joining and bending and forking. Olive had to squint to see it, but on each branch and twig, a name was written in tiny, pointed letters. Most of them were names she had never seen before:

Athdar McMartin, Ansley McMartin, Aillil McMartin

. But near the top, in the very center of the tree, Olive found a name she recognized:

Aldous McMartin

. This name branched off toward

Albert McMartin,

and then to

Annabelle McMartin.

The branch from Annabelle went nowhere. It trailed away between the blue leaves at the very top of the page, dwindling into a line so thin that it finally became invisible.

Athdar McMartin, Ansley McMartin, Aillil McMartin

. But near the top, in the very center of the tree, Olive found a name she recognized:

Aldous McMartin

. This name branched off toward

Albert McMartin,

and then to

Annabelle McMartin.

The branch from Annabelle went nowhere. It trailed away between the blue leaves at the very top of the page, dwindling into a line so thin that it finally became invisible.

Olive wriggled deeper into her pillows and carefully turned the page.

Sleeping spell

. The word

spell

sent a happy little shock down to her toes. Olive skimmed the thick yellow paper. There were lots of words she didn’t recognize—

valerian

and

boneset

and

witchnail

—but most of the words were things she knew or sort of knew, like

chamomile

and

nightshade

. Even when the words were familiar, like

cup

or

water

or

bird’s wing,

the delicate, thorny calligraphy transformed them into something mysterious and completely new.

. The word

spell

sent a happy little shock down to her toes. Olive skimmed the thick yellow paper. There were lots of words she didn’t recognize—

valerian

and

boneset

and

witchnail

—but most of the words were things she knew or sort of knew, like

chamomile

and

nightshade

. Even when the words were familiar, like

cup

or

water

or

bird’s wing,

the delicate, thorny calligraphy transformed them into something mysterious and completely new.

The whole first portion of the book seemed to be about sleeping. There were spells to bring sweet dreams and spells to send nightmares and spells to make sleepwalkers fetch things for you. Reading about sleep was making her sleepy. Olive settled down onto her back, holding the book up above her and flipping to the next section. Here were spells that looked more like recipes: potions for winning hearts and erasing memories, a cake that made everyone who ate it angry at each other.

Olive read on, fighting the tiredness that kept threatening to slam her eyelids down.

To Attract Paper Cuts. To Give a Headache. To Cause Uncomfortable Flatulence.

(Olive had to look up that last word in her dictionary.)

To Bring on a Fever. To Break a Bone.

The instructions were getting more and more complicated, full of ingredients she didn’t recognize or couldn’t imagine gathering—like frogs’ tongues. Where would a person get frogs’ tongues? Olive knew that some people ate frogs’

legs

, but she’d never seen frogs’ tongues in a grocery store . . .

To Attract Paper Cuts. To Give a Headache. To Cause Uncomfortable Flatulence.

(Olive had to look up that last word in her dictionary.)

To Bring on a Fever. To Break a Bone.

The instructions were getting more and more complicated, full of ingredients she didn’t recognize or couldn’t imagine gathering—like frogs’ tongues. Where would a person get frogs’ tongues? Olive knew that some people ate frogs’

legs

, but she’d never seen frogs’ tongues in a grocery store . . .

Wait a minute,

said a distant, nudging voice from the very back corner of Olive’s mind. Wasn’t there something she was supposed to be looking for? Olive peeled her eyes away from the book for a moment, glancing around the room. The sky beyond the window was lightening very softly, like deep purple cloth after years of washing. It could have been either dawn or twilight. It looked like the sky in Morton’s world.

said a distant, nudging voice from the very back corner of Olive’s mind. Wasn’t there something she was supposed to be looking for? Olive peeled her eyes away from the book for a moment, glancing around the room. The sky beyond the window was lightening very softly, like deep purple cloth after years of washing. It could have been either dawn or twilight. It looked like the sky in Morton’s world.

Morton.

Olive jerked upright. That was it. She was going to find a way to help Morton. Her eyes fell back on the book. But there were so many more pages to go, so many more interesting spells to read . . . There would be plenty of time to think about Morton. She would get to it later.

Olive jerked upright. That was it. She was going to find a way to help Morton. Her eyes fell back on the book. But there were so many more pages to go, so many more interesting spells to read . . . There would be plenty of time to think about Morton. She would get to it later.

Olive nestled her head against the pillow and raised the heavy book again. If only she didn’t feel so sleepy . . .

Her eyelashes were tugging at her eyelids like a hundred little curtain-pulls. Her arms began to sag. The book slid down, gently, heavily, and came to rest on Olive’s rib cage. She breathed in its dusty smell. It smelled like the floor of an antique shop, like ballet slippers hidden in a drawer for years, and like something sharper, like rust or cinnamon. Perhaps like fingerprints left five hundred years ago, in Scotland, in a house that had been turned to ash.

When she fell asleep, it was with the light still on and the open book forming a little roof above her heart. For the rest of the night she wandered through dreams full of trees and clutching hands and blowing paper. In the longest, clearest dream, she was part of the ground—in the ground, or beneath the ground—with a tree growing up out of her heart, its heavy trunk reaching from her toward the sky.

Olive slept and slept and slept. On her chest, the book rose and fell with each breath.

12

S

OMETHING WAS MAKING a thumping sound. Olive nestled deeper into the pillows and squinched her eyes shut. “No thank you,” she mumbled. “I don’t need a refill.”

OMETHING WAS MAKING a thumping sound. Olive nestled deeper into the pillows and squinched her eyes shut. “No thank you,” she mumbled. “I don’t need a refill.”

But the thing kept thumping. Slowly, Olive opened her eyes, and the hamburger and Coke she’d been enjoying dwindled away into her own rumpled bedspread. The book was still open on her chest, her room was drenched with bright yellow sunlight, she was very, very hungry, and a huge bumblebee was thumping its face stubbornly against her window.

Olive glanced at the alarm clock:

12:31

, said the red digits. She had never slept so late in her whole life, not even when she’d been delirious with a fever of 104 and thought that her toes had all traded places. No wonder she was hungry.

12:31

, said the red digits. She had never slept so late in her whole life, not even when she’d been delirious with a fever of 104 and thought that her toes had all traded places. No wonder she was hungry.

Dressed in fairly clean shorts and a T-shirt and carrying the spellbook in both arms, Olive stumbled out into the upstairs hall. “Mom?” she called. “Dad?” But the big house was quiet.

She jogged down the stairs, the heavy book thumping against her hip, and craned around the corner toward the shiny carved squares of the library’s double doors. “Hello! Anybody home?” Her voice rang against the walls and faded away.

In the kitchen, a note in her mother’s handwriting hung on the refrigerator door.

“Good morning, dear,” read the note. “Gone to campus. Back between 4:06 and 4:09, depending on traffic and other variables. Help yourself to 1/6 of the leftover lasagna for lunch. Love, Mom and Dad.”

Olive decided she’d prefer a big bowl of Sugar Puffy Kitten Bits to figuring out how much one-sixth of the lasagna was. She placed the spellbook on the counter in front of her, poured a heaping bowl of cereal, and sat down on one of the high stools. For a second, she was tempted to offer the book a bite of cereal—but that was silly, of course.

Olive often read while she ate (or ate while she read, as reading was the thing that usually continued both before and after). But this morning, even as hungry as she was, her cereal got pretty soggy. Whenever she tried to turn her attention to her increasingly un-puffy Kitten Bits, the book seemed to tug her back, urging her to read one more word, one more line, one more page. And soon she came to a group of spells that almost made her forget about breakfast entirely.

To Conjure a Familiar,

said the first.

said the first.

Olive skimmed the list of ingredients. It was a horrible spell, involving human blood and a cat’s eye, and something that came out of a toad’s stomach. When all the ingredients were combined, boiled together on a fire of elder branches under the thinnest crescent moon, a creature would appear, called up from another world to serve its master. Forever.

Her eyes scanned the spell again. So this was how the McMartins had taken possession of Horatio, Leopold, and Harvey. She imagined some long-dead McMartin—perhaps it was Athdar or Aillil, or someone even farther down the trunk of that blue-inked family tree—standing over the red glow of a fire somewhere in the craggy Scottish hills. Olive bumped the cereal bowl aside and pulled the book closer.

To Control Your Familiar,

read the next spell.

To Punish Your Familiar.

And, after that:

To Summon Your Familiar.

read the next spell.

To Punish Your Familiar.

And, after that:

To Summon Your Familiar.

The words fit into Olive’s mind like a key into an invisible lock. She could almost hear the tick of the bolt pulling back, the gears starting to turn. If she got this spell to work, she might finally be able to explore whatever lay beneath the basement’s trapdoor. Leopold wouldn’t stand guard over it for no reason; there

had

to be something there, something important, something that would reveal new secrets about the house, the McMartins, or Elsewhere itself. She could use this spell to get Leopold out of the way.

had

to be something there, something important, something that would reveal new secrets about the house, the McMartins, or Elsewhere itself. She could use this spell to get Leopold out of the way.

Without taking her eyes off the book, Olive scooped up a spoonful of cereal and chewed distractedly. The steps in the process looked fairly simple; she didn’t have to bury anything for six months and dig it up by the light of a full moon (that was one of the instructions she’d seen on another page), and she didn’t have to do anything that might accidentally light the house on fire. The spell only required white chalk, milk, “a trace of your familiar: fur or feather, hide or hair,” and several unusual plants. Olive had milk and chalk, she could get the fur . . . and she knew where to look for unusual plants.

Other books

Finger Prints by Barbara Delinsky

Second Thyme Around by Katie Fforde

Death Day by Shaun Hutson

Remote by Cortez, Donn

Winterbay by J. Barton Mitchell

Murder on Ice by Ted Wood

Sight Reading by Daphne Kalotay

Land of Love and Drowning: A Novel by Tiphanie Yanique

The Glass Village by Ellery Queen

B009QTK5QA EBOK by Shelby, Jeff