Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere (25 page)

Read Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

“You brought your friends,” Annabelle went on, turning her tiny smile to Morton and Leopold in turn. “How nice of you, to get them mixed up in all of this again. Hello, Leopold.” The cat stiffened. “Hello, Morton. I wondered when I would see you again.”

Keeping her arm carefully hidden behind Morton, Olive groped for the flashlight that was wedged in her pocket. But before she could even wrap her shaking hand around it, the flashlight flew out from between her fingers, rolling past Annabelle’s feet in their little high heels and out into the hallway.

“That isn’t going to work this time,” said Annabelle sweetly, lowering her hand. “I’m better prepared for your tricks. And, obviously, you haven’t come up with anything new.” She laughed, a light, gentle laugh. “In fact, you’ve done almost

exactly

what we wanted you to do. You used the book, estranged your friends, dug up the painting,

brought

us the spectacles. If you had jumped off of the roof last night, it would have been a bit easier, but . . . Oh, well.” Annabelle sighed lightly, as though a batch of cookies she’d been baking had gotten a little too brown. “We can handle it this way too, I suppose.” She took a step closer, her eyes traveling from Olive to Morton and Leopold. “Three birds with one stone, as they say.”

exactly

what we wanted you to do. You used the book, estranged your friends, dug up the painting,

brought

us the spectacles. If you had jumped off of the roof last night, it would have been a bit easier, but . . . Oh, well.” Annabelle sighed lightly, as though a batch of cookies she’d been baking had gotten a little too brown. “We can handle it this way too, I suppose.” She took a step closer, her eyes traveling from Olive to Morton and Leopold. “Three birds with one stone, as they say.”

“It’s

two

birds,” blurted Morton.

two

birds,” blurted Morton.

Annabelle’s smile widened. “Well, aren’t you irritating,” she told Morton, her inflection the same as if she’d said

Well, aren’t you precious

. “I can see why your sister wanted to get rid of you.”

Well, aren’t you precious

. “I can see why your sister wanted to get rid of you.”

Morton hopped out of Olive’s lap. He squared his shoulders, squeezing the blue horse tightly in his arms. “She did not,” he said loudly. “You made her do bad things. Lucy loved us. You

made

her do it.” He stomped his foot, and the fedora on his round head tipped rakishly over one ear.

made

her do it.” He stomped his foot, and the fedora on his round head tipped rakishly over one ear.

“Let’s ask her about that, shall we?” Annabelle, still smiling, made a little sign in the air with one hand. There was the sound of a door slamming, followed by footsteps clicking quickly up the stairs.

“Yes, Annabelle?” panted Mrs. Nivens, hurrying through the bedroom doorway. She halted suddenly, as if she’d hit an invisible wall. Her eyes flicked from Olive, still leaning against the painting, to the large black cat positioned protectively before her, to the small, tufty-haired, trench-coated boy clutching a blue corduroy horse.

“Morton,”

she gasped. Her hands flew up to her chest, clutching handfuls of her neatly ironed blouse. Olive would have worried about Mrs. Nivens’s heart, but she reminded herself that Mrs. Nivens didn’t have one—not anymore.

she gasped. Her hands flew up to her chest, clutching handfuls of her neatly ironed blouse. Olive would have worried about Mrs. Nivens’s heart, but she reminded herself that Mrs. Nivens didn’t have one—not anymore.

“Lucy?” Morton whispered. He stepped closer to her, staring up. A small frown creased his broad white forehead. “You look so . . .

different

.”

different

.”

Mrs. Nivens’s glassy eyes were wide. A smile trembled on her lips, jerking them sideways as she spoke. “And you look exactly the same, Morton.”

Watching her, Olive wondered if Mrs. Nivens was about to cry. But of course she

couldn’t

cry. Not real tears, anyway. Only one thing seemed certain: For the moment, Mrs. Nivens had forgotten about everyone else in the room. As subtly as she could, Olive nudged Leopold with her foot and then nodded toward the hall, where the flashlight lay. Leopold edged slowly toward Morton’s side. Olive tried to shift onto her knees, getting ready to run, if necessary, but Annabelle’s eyes honed in on her, their painted pools wary and bright. Olive froze.

couldn’t

cry. Not real tears, anyway. Only one thing seemed certain: For the moment, Mrs. Nivens had forgotten about everyone else in the room. As subtly as she could, Olive nudged Leopold with her foot and then nodded toward the hall, where the flashlight lay. Leopold edged slowly toward Morton’s side. Olive tried to shift onto her knees, getting ready to run, if necessary, but Annabelle’s eyes honed in on her, their painted pools wary and bright. Olive froze.

“Was it you?” Morton was asking, his voice still not much more than a whisper. “Was it? Did you really ask the Old Man to take me away?”

“I told him not to hurt you,” said Mrs. Nivens, sidestepping the question. “And he didn’t. See?” Mrs. Nivens crouched in front of Morton, bringing their faces level. For a second, Olive could almost picture the Lucinda Nivens of eighty years ago, kneeling down to speak eye to eye with her little brother. “You get to live forever. Just like me.”

Morton shook his head. He shook it harder and harder, until his face became a blur. “No,” he said, stopping. “I’m just

stuck

. I’m stuck being

nine

forever.” He glared up at his sister. “But at least I’m not stuck being an ugly old lady.”

stuck

. I’m stuck being

nine

forever.” He glared up at his sister. “But at least I’m not stuck being an ugly old lady.”

“Morton!” gasped Mrs. Nivens.

“What? Are you going to

tell

on me?” taunted Morton. “It was always

Morton, the bad boy

and

Lucinda, the good girl

. But you were just pretending. You were tricking them.” Morton choked, the anger in his voice suddenly trickling away. “What did he do with them?” he asked softly. “Where are Mama and Papa?”

tell

on me?” taunted Morton. “It was always

Morton, the bad boy

and

Lucinda, the good girl

. But you were just pretending. You were tricking them.” Morton choked, the anger in his voice suddenly trickling away. “What did he do with them?” he asked softly. “Where are Mama and Papa?”

Mrs. Nivens shook her head. “Morton . . .” she began, “. . . I don’t know.”

“Yes you do,” argued Morton. “What did he do to them?”

“He—he put them someplace safe. Like you. He didn’t hurt them. I

asked

him not to hurt them—”

asked

him not to hurt them—”

“You’re so STUPID!” yelled Morton, his body quaking with fury. “Why should

he

do what

you

said? Where are they? WHAT HAPPENED TO THEM?”

he

do what

you

said? Where are they? WHAT HAPPENED TO THEM?”

“Morton, I honestly don’t know. Honestly,” said Mrs. Nivens, a pleading note slipping into her voice. “Annabelle,” she ventured, “do

you

know?”

you

know?”

Annabelle gave a sigh. Leopold took advantage of her momentarily closed eyes to slip closer to the doorway. “Really, Lucinda,” Annabelle said, “you would have to be much less sentimental to even

hope

to become one of us.”

hope

to become one of us.”

“I’m sorry, Annabelle,” said Mrs. Nivens, getting swiftly to her feet and backing away from Morton.

There was a sudden loud yowl as Leopold flew through the air, kicked backward by Annabelle’s high heel. He landed next to Olive, in front of the painting.

“You know I don’t like to fight a lady—” the cat huffed, getting back to his feet and baring his claws.

“Fight me?” Annabelle interrupted him with a laugh. “Once we’ve taken care of these two, I will deal with you, Leopold. Now stand aside.” Annabelle muttered something and made a sweeping motion with her arm.

Dragged by an invisible leash, Leopold slid backward across the floor and smacked into the opposite wall. There he stuck, hissing and growling, as though his fur had been Velcro-ed to the plaster.

“Now, take out the spectacles, Lucinda.”

Obediently, Mrs. Nivens pulled the spectacles out of her skirt pocket. Faint daylight leaking through the lace curtains glinted softly on their lenses. Olive’s heart gave a desperate leap before flopping back into its place again. Even if she could get the spectacles away from Mrs. Nivens, there was no way she could physically overpower both women. She chewed the inside of her cheek so hard she could taste blood.

“What are you going to do?” Mrs. Nivens asked in a very small voice, glancing at Annabelle.

“Only what they did to me,” said Annabelle. “We’re going to put the two of them in this painting. Then we’re going to destroy it before they manage to get out and annoy us further.”

“Destroy it?” Mrs. Nivens repeated.

“Yes,” Annabelle said lightly. “We’re going to burn it.”

Morton let out a squeak and backed quickly toward Olive. She pulled him down beside her, wrapping her arm around his shoulders and pressing her back against the painting to stay as far from Annabelle as possible. She shot a look at Leopold, who was writhing and hissing wildly against the wall.

“You can’t do that,” said Olive, trying to sound angry rather than terrified, and not quite succeeding.

Annabelle’s prettily arched eyebrows went up. “Olive, dear,” she said sweetly, “you got yourself into this.” She turned to Lucinda. “Put on the spectacles.”

Mrs. Nivens hesitated. “Why does

he

have to go in?” she whispered, tilting her head toward Morton, who was huddled tight against Olive’s shoulder. “Couldn’t we just put him back in some other painting?”

he

have to go in?” she whispered, tilting her head toward Morton, who was huddled tight against Olive’s shoulder. “Couldn’t we just put him back in some other painting?”

“No, we couldn’t,” said Annabelle. “So much sentiment, Lucinda. Do you want to be part of our family, or not? Do you want me to teach you, or not?” Her voice was losing its sweetness. “Are you loyal to us . . . or not?”

Mrs. Nivens wavered, glancing at Morton. “But what has he done? It’s all Olive’s fault. Why does Morton have to be punished too?”

“Because

I said so,

” said Annabelle, very low, stepping closer to Mrs. Nivens. They were almost exactly the same height, but something about Annabelle’s voice or her way of moving made her seem twice as large as Mrs. Nivens. “Give me the spectacles, if you’re too weak to do this.” In the next second, she had tugged them out of Mrs. Nivens’s unresisting hand.

I said so,

” said Annabelle, very low, stepping closer to Mrs. Nivens. They were almost exactly the same height, but something about Annabelle’s voice or her way of moving made her seem twice as large as Mrs. Nivens. “Give me the spectacles, if you’re too weak to do this.” In the next second, she had tugged them out of Mrs. Nivens’s unresisting hand.

Annabelle crossed the room so quickly that Olive couldn’t even squirm out of the way. Before she knew it, Annabelle was crouching in front of her, with her brown eyes glowing behind the spectacles’ lenses, and her cold, painted hand pressed against Olive’s chest.

The moment Annabelle touched her, Olive felt the canvas behind her back turn to jelly. Her spine began to sink inward. The cool night breeze of the painted forest slipped through the fabric of her shirt. Beside her, Morton was being shoved backward too, fighting to pull himself upright again.

“Morton!” Olive yelled. “Grab on to the frame!”

Morton’s fingers, lost inside the trench coat sleeves, scrabbled at the heavy gold frame. Olive braced him with one arm and reached out for the frame’s other side, clamping her hand around it. Across the room, Leopold hissed and struggled helplessly.

“Help!” Morton shouted. “Lucy, help!”

But Mrs. Nivens didn’t move. She stood still, several steps behind Annabelle, looking more than ever like something carved out of butter and unable to move on its own.

“Shh,” whispered Annabelle, her lips curved in a sweet little smile. “Let’s not disturb the neighbors.”

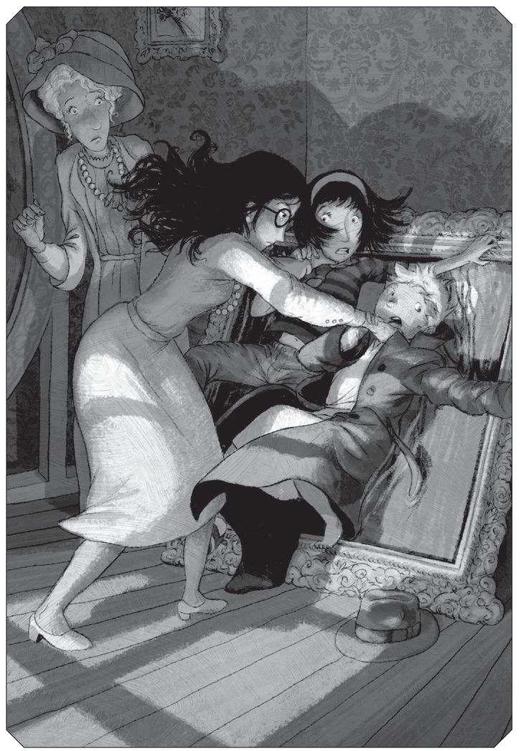

Her cold, strong hands wrapped around Olive’s and Morton’s throats. Both of them let go of the frame, trying to pry her fingers away, and immediately began to tilt backward into the dark and windy forest.

“NO!” Olive choked, thrashing and kicking in an attempt to knock the spectacles off of Annabelle’s smiling face. The muscles in her stomach and her legs were burning with effort, and it was getting harder and harder to breathe. “Harvey! Rutherford! Help!” But Annabelle’s reach was long, and she kept her icy hand clamped tight around Olive’s throat, forcing her into the painting.

“Help!” Olive screamed again, just before the upper half of her body toppled backward. Annabelle gave her a powerful shove, and Olive found herself suddenly hanging upside down inside the painting, with her legs locked around the bottom of the frame as though it were a rung on the monkey bars. Cold air and darkness washed over her. The bony trees hung, upside down, in front of her, beckoning with their bare branches. Just above her, she glimpsed Morton’s terrified face and thrashing arms as Annabelle tried to push him in after her.

“No,” she heard someone say. “You can’t do this to him!”

Annabelle’s face vanished from the frame. Morton reached out, grabbing Olive’s arm, and she managed to swing herself up into sitting position. Holding on to each other, they scrambled over the edge of the frame. Olive felt the forest wind die away as the canvas turned solid behind them.

Mrs. Nivens had grasped Annabelle by the back of the blouse, yanking her toward the center of the bedroom. As Olive and Morton watched, huddling against the side of the frame, Annabelle wheeled around and slapped Mrs. Nivens, hard, on the cheek. Then, holding her by both wrists, Annabelle shoved Mrs. Nivens backward across the floor, toward the painting.

“Climb in,” Annabelle said. “You and your little brother can burn together. It will be nice and cozy.”

“Wait,” said Mrs. Nivens, her voice rising, shrill and breathy. “You said—you promised to teach me, to take me into your family. I’ve served you all this time; I brought you back—”

Annabelle laughed a light, tinkling laugh, like bits of broken crystal falling to a stone floor. “

You,

Lucinda?” She shook her head. “If tonight has shown us anything, it’s that

you

are not the sort of apprentice we need.” Annabelle flicked her wrist, mumbling a few words that Olive couldn’t catch. Floating above the tips of her fingers appeared a small, shimmering ball of fire. “Now, climb in, or I’ll burn your little brother right here.”

You,

Lucinda?” She shook her head. “If tonight has shown us anything, it’s that

you

are not the sort of apprentice we need.” Annabelle flicked her wrist, mumbling a few words that Olive couldn’t catch. Floating above the tips of her fingers appeared a small, shimmering ball of fire. “Now, climb in, or I’ll burn your little brother right here.”

Other books

The Disappearing Dwarf by James P. Blaylock

Millionaire Teacher by Andrew Hallam

Conklin's Foundation (Conklin's Trilogy) by Page, Brooke

Lucid by A.K. Harris

The Runaway by Martina Cole

Epitaph by Mary Doria Russell

Drama 99 FM by Janine A. Morris

Falling Into You by Abrams, Lauren