Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere (3 page)

Read Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

“Harvey?” she called, under her breath. But there was no cat to be seen on Mrs. Nivens’s perfect lawn, or in her flowerbeds, or in the branches of her neatly pruned trees.

Olive skulked across Mrs. Nivens’s yard, where tall shrubs and a fence divided the lawn from the alley. Mrs. Nivens, clipping coupons in her living room, noticed a pale blur moving through her hydrangeas, but reached the window too late to see anything but a telltale tremor from the borderline of Mrs. Dewey’s birch trees next door.

Olive crouched in the knot of papery birch trunks, looking around for the next clue. If mystery books had taught her anything (and they had taught Olive much of what she knew), there was always another clue to find, if the detective knew how to look. And, as it happened, the next clue was hanging right in front of Olive’s face.

A long green tail, with blotches of many-colored fur peeping through, twitched in the leaves above her. Olive looked up. Perched in the branches was the rest of a green-painted cat.

“Harvey!” Olive exclaimed. “What are you doing?”

The cat glanced over his shoulder. “Shh,” he hissed. “Don’t blow my cover. Call me by my code name: Agent 1-800.”

Olive lowered her voice. “What’s going on, Agent 1-800?”

“Climb up, and I’ll give you a quick briefing.”

Olive pulled herself onto the lowest branch of the birch tree. Harvey moved aside to give her room and left a few more streaks of green on the tree’s white bark.

“It’s going to take forever to get that paint out of your fur,” Olive whispered.

“Camouflage was necessary,” Harvey replied in an accent that was faintly British, turning his streaky green face toward Mrs. Dewey’s backyard. “Sometimes a secret agent must do unpleasant things in the line of duty.” He ran one paw across his nose, smearing away a drip of paint. “Here’s the info. Top secret. Classified. For your ears only.”

“Understood,” whispered Olive.

“A foreign element has infiltrated the home territory.”

Olive thought of the table of elements that hung in the science classroom at her last school. Were any of them foreign? She supposed a lot of them came from other countries. “What do you mean?” she asked. “Like Lithuanium?”

“Like

this,

” said Harvey, pushing aside a leafy branch so that Olive could peek through.

this,

” said Harvey, pushing aside a leafy branch so that Olive could peek through.

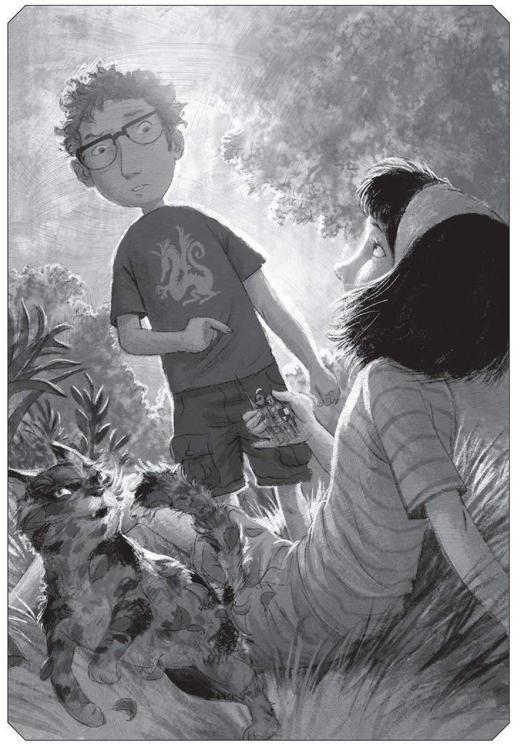

Below them, in Mrs. Dewey’s shady backyard, a boy sat at a wooden picnic table. Both the picnic table and the boy looked rather tired and dirty. The boy was smallish, thin, and long-limbed, with dark brown hair that curled and stuck up in various directions. He wore wire-frame glasses and a gray T-shirt with a picture of a dragon on the front of it. He was painting a model castle with a miniature brush, and frowning a little, the way people frown when they’re trying to thread a needle.

“Who is that?” Olive asked.

“That’s the foreign element. The infiltrator. The

spy

.”

spy

.”

The boy put down the first paintbrush and picked up an even tinier one. He dabbed carefully at the edge of the castle. Olive noticed that both the boy and the picnic table were spattered with dots of paint, but the castle was immaculate.

“What makes you think he’s a spy, Agent 1-800?” she whispered into the cat’s ear.

“Just look at him!” hissed Harvey. “The devious smile. The shifty eyes.”

Olive leaned forward, trying to get a better look at the boy. And, at that moment, the boy realized he was being watched. He stopped dabbing at the castle. Slowly he looked up into the green-gold leaves of the birch tree, where Olive and Harvey sat, staring straight back at him.

“Rutherford!” hooted a voice.

Mrs. Dewey’s round body, looking extra snowmanlike in a snug white sundress, came trotting quickly across the lawn.

“Rutherford Dewey,” Mrs. Dewey huffed, “just look what you’re doing to my picnic table! And to your shirt!” Mrs. Dewey tugged the tiny paintbrush out of the boy’s hand. “What did I tell you about spreading newspapers on the table? Now go rinse your shirt before the paint sets in.”

The boy took one last, silent look at the tree. His eyes met Olive’s. For what seemed like a long time, they stared at each other, each trying not to be the one who blinked. Then Mrs. Dewey grabbed the boy by the shoulder and hustled him toward the house.

Harvey let out a breath. “That was close, Olive,” he said. “Next time, you’d better paint yourself before going undercover.”

3

H

ARVEY, STILL GREEN and forbidden to come inside until he wasn’t, spent the night on the porch steps. The next morning he was nowhere to be found.

ARVEY, STILL GREEN and forbidden to come inside until he wasn’t, spent the night on the porch steps. The next morning he was nowhere to be found.

Olive knew he was probably hiding nearby, postponing a bath for as long as possible, so she lay on the back porch trying to read a Sherlock Holmes book while Horatio dozed on a windowsill and Leopold patrolled the basement. She would rather have been exploring than reading, but once again, both nongreen cats had made excuses when she asked them to take her Elsewhere.

She didn’t like having to ask them in the first place. Olive was the type of girl who would rather climb a teetering stack of chairs up to a high shelf than ask for help, perhaps because she had a lot more practice at falling down than she did at talking to people. Back when she had the spectacles, she could go wherever she wanted, whenever she wanted, without having to ask anyone’s permission. Now she had to beg three moody cats for the favor. It made her whole body itch just to think about it.

It was another humid, lazy day. Linden Street was soaked with sun, its green lawns sparkling and gardens blooming. Behind the big stone house, however, the yard was dim and murky. Towering trees cast a net of shadows over the jumbled garden. In one far corner, near the compost heap, a patch of bare dirt marked the spot where Olive had buried the painting of the forest, with a howling Annabelle McMartin still trapped inside. It looked like a fresh grave. And no matter where Olive moved to try to find a patch of light, the shadow of the house seemed to follow her. Once or twice, she nodded off in the sun and woke up in the humid shade, with her face stuck to the book’s pages.

She was just peeling her cheek off of

A Study in Scarlet

for the third time when she noticed a flurry of movement across the backyard. She crawled to the edge of the porch. At the back of the lawn, deep in the overgrown dogwood shrubs, a branch rustled.

A Study in Scarlet

for the third time when she noticed a flurry of movement across the backyard. She crawled to the edge of the porch. At the back of the lawn, deep in the overgrown dogwood shrubs, a branch rustled.

Olive left her book on the steps and tiptoed across the grass.

“What do you have to say for yourselves now?” a voice hissed from the dogwoods—a voice with a faintly British accent. Olive crouched down next to the shrubs.

“So, you refuse to talk, do you?” she heard Harvey say. “Well, we have ways of encouraging you. Perhaps we will chip your lovely paint—like this!” There was a little

tink

sound of a claw hitting metal. “Still not talking? Oh, you’re a stubborn bunch, aren’t you? But we have a few more tricks up our sleeves—”

tink

sound of a claw hitting metal. “Still not talking? Oh, you’re a stubborn bunch, aren’t you? But we have a few more tricks up our sleeves—”

“Aha!” shouted Olive, thrusting the dogwood branches apart with both arms. “Found you!”

“Gah!” shouted Harvey, so startled that he toppled over backward.

“What on earth are you doing, Harvey?”

“

Agent 1-800!

” the cat spluttered, struggling back to his feet. His paint-splotched fur had dried so that it stuck up in some directions and was smooshed flat in others. Little leaves and twigs clung to it like Christmas ornaments. “I was interrogating these enemy spies, but they refuse to give up their secrets.” Harvey turned back to his captives with a burning glare.

Agent 1-800!

” the cat spluttered, struggling back to his feet. His paint-splotched fur had dried so that it stuck up in some directions and was smooshed flat in others. Little leaves and twigs clung to it like Christmas ornaments. “I was interrogating these enemy spies, but they refuse to give up their secrets.” Harvey turned back to his captives with a burning glare.

Olive followed Harvey’s eyes. Among the dogwood twigs stood a row of little metal figurines. They were models of knights, some on horseback, others holding raised swords. The models had been carefully painted, right down to the teeniest details. Harvey was right about one thing: They weren’t talking.

“Where did you get these?” Olive asked, although she already had a pretty good idea.

“They were captured on enemy territory,” said Harvey. He inched closer to Olive, his eyes wide. “Who knows what dangerous secrets they are keeping?”

Olive looked down at the figurines. They stared back at her innocently.

“Excuse me,” said a voice.

Now it was Olive’s turn to topple over backward. Harvey leaped out of the dogwoods and caromed toward the branches of a nearby maple tree.

Olive looked up. Beside her stood the boy from Mrs. Dewey’s backyard. He was slightly cleaner than yesterday, but he still looked as if he’d been hustled out of bed a few hours too early. His brown hair stuck up in confused, curly tufts. He was wearing a different T-shirt. This one had a dragon on it too.

“I think your cat took my models,” said the boy in a rapid, slightly nasal voice.

“I guess . . . I mean . . . you mean these?” Olive scooped up the figurines and held them out to the boy between her fingertips, being careful not to actually touch him. “Sorry.”

“I’m an expert on the Middle Ages,” the boy blurted. “Well, on the Middle Ages in Western Europe, primarily Britain and France. I’m a semi-expert on dinosaurs. My favorite right now is the plesiosaur. I used to like the brachiosaurus—that was the largest of the sauropods—but now I’m more interested in aquatic dinosaurs. Have you ever heard of the coelacanth?”

Those were the words the boy said. He said them so quickly, they sounded more like this to Olive: “Iusedtolikethebrakiosoristhatwasthelargestofthesoreopods–butnowI’mmoreinterestedinaquaticdinosaurshaveyoueverheardofthesealocanth?”

“The seal what?” said Olive.

“Coelacanth,” the boy repeated. He jiggled back and forth on his feet while he spoke. “A living fossil. A coelacanth was caught by a fisherman near South Africa in 1938, when everybody thought they’d been extinct for millions of years. I have a theory that there are lots of other surviving species of dinosaurs, still living deep in the ocean, and we just haven’t found them yet.”

“Okay,” said Olive very slowly.

“What about you?” said the boy. “What are your interests?” Behind their smudgy lenses, his wide brown eyes blinked at Olive expectantly.

Olive thought fast. She liked to read scary stories while eating Tang straight from the can. She liked to collect bottles from kinds of pop no one had tasted in forty years. She liked to decorate smooth rocks with fingernail polish. But all of these things sounded strange, somehow, when she said them aloud. So, instead, because the boy was still staring straight down at her, she said, “My house used to be owned by witches.”

Immediately, she couldn’t believe she had said those words. Aloud. Out of all the words in the world. If the universe had had a rewind button, Olive would have definitely pushed it. In fact, she would really, really have liked to rewind past the point when the boy had said “excuse me” and she had fallen over onto her behind.

The boy straightened his smudgy glasses. “Interesting,” he said. “What kind of witches?”

“What kind?”

“White witches, green witches, dark witches . . .”

“Dark,” said Olive with certainty.

“How did you find out about them? Were there record books or journals? Did you have an expert occultist examine the house?”

“No . . .” said Olive. “They left all their stuff here.”

The boy stopped jiggling. He looked hard at Olive, and his eyes were large and very dark brown. “Interesting,” he said again, but more quietly. “Have you found their grimoire?”

“Grimoire?” Olive repeated.

“Their book of spells.”

Olive blinked. “No.”

“You should look for it,” said the boy. “Every witch has one. It might provide some very important information.”

“Maybe,” said Olive, feeling a bit angry that she hadn’t thought of this before.

Meanwhile, the voice in her brain was shouting,

OF COURSE!

If she knew the McMartins’ spells, maybe she could find a new way into Elsewhere! Maybe she could even make her own magic spectacles. Maybe there would be some hint about how to help Morton. Olive’s heart began to pound.

OF COURSE!

If she knew the McMartins’ spells, maybe she could find a new way into Elsewhere! Maybe she could even make her own magic spectacles. Maybe there would be some hint about how to help Morton. Olive’s heart began to pound.

The boy held up a knight figurine, turning it in the patchy sunlight. “This one seems to be chipped,” he said. “I’d better go repair it.” Abruptly, he turned and headed toward the lilac hedge. Then he stopped and looked back at Olive. “My name is Rutherford,” he said.

Other books

Warshawski 01 - Indemnity Only by Paretsky, Sara

Katie and the Mustang, Book 4 by Kathleen Duey

Mistletoe Menage by Molly Ann Wishlade

Beach Winds by Greene, Grace

A Planet for Rent by Yoss

All I Want by Erica Ridley

The Naked Prince by Sally MacKenzie

The Pakistan Conspiracy, A Novel Of Espionage by Francesca Salerno

Crystal Horizon: A Short Prequel to Crystal Deception by Doug J. Cooper

Tiger's Lily by Cheyenne Meadows