Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (10 page)

Read Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America Online

Authors: Harvey Klehr;John Earl Haynes;Alexander Vassiliev

Later the same day judge Eady gave his verdict on "qualified privilege," and the defendant succeeded here too. The judge also decided that

the contents of John Lowenthal's allegations in the article and in his re view posted on Amazon.com were similar, and there was no need to have

a trial of my case against Amazon; this meant I had lost that case as well.

(I didn't dwell here on my case against Amazon because it based its defense mostly on the 1996 Communications Decency Act, claiming the

act gave Amazon immunity from prosecution, and the discussions we had

were mostly on technical and legal matters.)

When I got back home, I couldn't look my wife Elena in the eye. She

was very tired of my literary adventures, which had started ten years before. I felt absolutely devastated. Our son, Ken, was unusually quiet in his

room. I didn't follow the reaction to the trial on the Web; I couldn't stand

seeing the name of Alger Hiss, even a different name starting with "A"

and "H." Much later I tried to find on the Web site of The Nation any

mention of the trial since its reporter had been present every day in the

courtroom. There was nothing. I learned that in September 2003 John

Lowenthal died of cancer. I was sure I was through with espionage history. But in 2005 I got interested in Wikipedia and went to its site to check

how accurate it was. And I decided to have a look at the article about ...

Alger Hiss!

There were some external links at the end of the article, and one of

them led to John Haynes's Web site. I knew John and his co-author, Harvey Klehr, by reputation, and I clicked on the link. I had a look at some

pages at his site, and suddenly I saw my handwriting: it was Anatoly

Gorsky's list, a copy of which I had presented as evidence during the trial;

somehow it had reached John. And there were some comments by David

Lowenthal, John Lowenthal's brother, questioning the accuracy of the

list. The Alger Hiss cult was still at it! I wrote to John Haynes, correcting

David Lowenthal's fantasies about my work at the SVR press bureau. And

that's how this book project started. John and Harvey were excited to

learn that I now had my original notebooks and convinced that they offered an opportunity to go well beyond what Allen and I had done in The

Haunted Wood in telling the story of Soviet espionage in the United

States.

I know this book will cause new discussions about Hiss, and I don't

want to be pulled into them. Alger Hiss is a religion, and there is no point

in arguing with people about their religious beliefs. My life is too short,

and it certainly didn't get longer after two years of litigation against Frank

Cass and Amazon.com. I've told my story, and I don't give a damn about

Alger Hiss. Never did.

Case Closed

lexander Vassiliev's notebooks quote KGB reports and cables

lexander Vassiliev's notebooks quote KGB reports and cables

from the mid-1930s to 1950 that document KGB knowledge of

and contacts with Alger Hiss and unequivocally identify Hiss as

a long-term espionage source of the KGB's sister agency, GRU,

Soviet military intelligence. Hiss is identified by his real name as well as

by cover names, "Jurist," "Ales," and "Leonard." The material fully corroborates the testimony and accounts of Whittaker Chambers, Hede

Massing, Noel Field, and others, while offering new details about Hiss's

relationship with Soviet intelligence.

No individual is a more potent symbol of American collaboration with

Soviet intelligence than Alger Hiss. From the moment of his confrontation with Whittaker Chambers in 1948, Hiss became the central figure in

a debate that has divided Americans for decades. On the one side stood

those who saw him as the archetype of a generation of young, collegeeducated people radicalized by the Depression, drawn to Washington during the heady days of the New Deal, and ultimately converted to communism. Intoxicated by their new ideology, they cooperated with Soviet

intelligence agencies and eventually betrayed liberalism's commitment

to political democracy and aided Stalin's totalitarian state. On the other

side are those who regarded Hiss as an innocent victim of anti-Communist paranoia, a New Deal idealist maliciously framed by right-wing

provocateurs backed by the reactionary wing of the Republican Party and

malign elements of the FBI who were eager to discredit liberalism and

taint the New Deal and the Democratic Party with treason.'

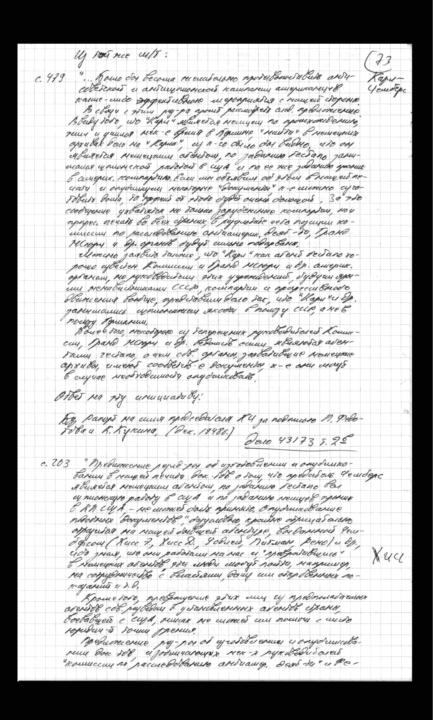

A 1948 KGB headquarters memo IistingAlger Hiss as one of "our former agents" who were betrayed by Whittaker Chambers in testimony to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Courtesy of Alexander

Vassiliev.

The Hiss-Chambers case riveted the nation as it moved from the halls

of Congress to the federal courtroom, where Hiss was convicted of perjury for lying about providing government secrets to Chambers, a selfconfessed Soviet agent handler. Not only was Hiss a seeming model of the

New Deal establishment-elite prep school, Johns Hopkins University,

Harvard Law School, protege of Felix Frankfurter, law clerk to Oliver

Wendell Holmes, and president of the Carnegie Foundation for International Peace-but he also had occupied important posts in the government, rising from an obscure lawyer for the Agricultural Adjustment

Administration (AAA) to become a senior diplomat, director of the State

Department's Office of Special Political Affairs, attending the 1945 threepower Yalta Conference as an adviser to President Roosevelt, and presiding at the founding conference of the United Nations. In addition to

these achievements, he was an elegant, handsome, charming, and distinguished-looking man.

That so obvious an exemplar of the reigning American liberal establishment might have been a Soviet spy in the 193os and may have continued to serve Soviet interests into the 1940s seemed incredible. Nevertheless, the evidence demonstrating that Hiss had long been living a

lie was substantial. Many people could discount Whittaker Chambers's

testimony about his relationship with Hiss as delusional or a provocation,

but they could not so easily dismiss the documents he produced. When

he broke with Soviet intelligence in 1938, Chambers kept materials given

to him by Hiss. Some were summaries or quoted extracts of State Department documents written in Hiss's hand or typed on a Hiss family

typewriter while others were photographs of State Department documents with Hiss's office stamp and his handwritten initials. In addition,

government investigators uncovered documentary evidence supporting

claims made by Chambers about the used car Hiss secretly donated to the

Communist Party and financial transactions between him and Hiss. Chambers's account of their friendship much more closely matched the

documented facts than Hiss's story of a short-lived, distant relationship.

Supporting witnesses also testified to Chambers's activities as the courier

and supervisor of a network of Soviet sources.

Following Hiss's conviction in 1950 his supporters began a campaign

that continues to this day to assert his innocence. Over the years they

have generated many theories to account for the evidence that convicted

him, ranging from an FBI conspiracy to a plot engineered by a sexually

spurned homosexual (Chambers). Despite massive evidence to the contrary, some have maintained that not only is there no convincing evidence

that Hiss was a spy, but also that Chambers was a fantasist who invented

his own work for the Soviets. In the 199os, one Hiss defender, his lawyer,

John Lowenthal, briefly persuaded former Soviet Army general and military historian Dmitri Volkogonov to claim that a search of Russian

archives had found no evidence to support the charge that Hiss had been

a Soviet agent or that Chambers himself had been one. Faced with skepticism and questions about how he could make such sweeping statements

in light of the contrary evidence, Volkogonov quickly retracted his statements, noting that he had been allowed to see only KGB material selected for him by agency officials and had not asked for information from

Soviet military intelligence files, despite the fact that Chambers and, presumably, Hiss had worked for the GRU. Volkogonov told the New York

Times, "The Ministry of Defense also has an intelligence service, which

is totally different.... I only looked through what the KGB had ... [but]

the attorney, Lowenthal, pushed me hard to say things of which I was not

fully convinced."2

Although Soviet intelligence archives themselves remained largely

closed to research after the 1991 collapse of the USSR, other Soviet-era

archives were opened. Files from the archives of the Comintern supported key elements of Chambers's story about the existence of a covert

American Communist Party apparatus headed by Josef Peters. Decrypted

World War II KGB cables from the National Security Agency's Venona

project corroborated Chambers's identification of mid-level government

officials as secret Communists and Soviet spies. Few of the cables the

Venona project decoded were from GRU, but one 1945 KGB cable reported contact with a GRU source, cover-named "Ales," whom American

security officers judged was "probably Alger Hiss." Finally, Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev's The Haunted Wood (1999) cited specific

KGB archival documents that explicitly named Hiss as a Soviet agent.

After a brief period of silence and confusion, Hiss's defenders regrouped and went on a counteroffensive. A new Web site dedicated to the

proposition that he had been framed emerged, hosted at New York University. Critics attacked The Haunted Wood on the grounds that only the

authors had access to its underlying documentation, parsed the Venona

project's "Ales" message, and offered elaborate and convoluted interpretations of why "Ales" might not be Hiss that were published in prestigious academic journals and promoted by left-wing journals of opinion

such as The Nation.

The earliest references to Hiss in the documents in Vassiliev's notebooks

recount a mid-1930s imbroglio involving Hiss, two KGB State Department sources (Laurence Duggan and Noel Field, discussed in chapter 4

below), and KGB operative Hede Massing. The situation developed as

follows. Duggan joined the U.S. State Department in 1930, rose rapidly,

and became head of the Latin American Division in 1935. Alerted to his

Communist sympathies by party contacts, Peter Gutzeit, head of the

KGB's legal station, reported in October 1934 that he had met with Duggan and was impressed with his willingness to assist the Soviet cause.

While the Latin American Division was not of major interest to the Soviets, Gutzeit noted that through Duggan the KGB could "`gain access to

Field-an analyst in the Euro. division of the State Department with

whom D. [Duggan] is on friendly terms,"' and Europe was Moscow's

chief intelligence target.3

Noel Field, born in 1904, had spent much of his childhood in Europe

but returned to the United States to attend Harvard. He joined the Department of State as a foreign service officer in 1926, became radicalized

in the late 192os, and began to read CPUSA literature and associate with

party members. His increasingly left-wing inclinations were known in the

State Department and blocked his hopes for a foreign diplomatic post. In

frustration, he shifted from its diplomatic service to its professional and

scientific service, whose staff focused on technical foreign relations issues. Field became a specialist in American interaction with the League

of Nations.