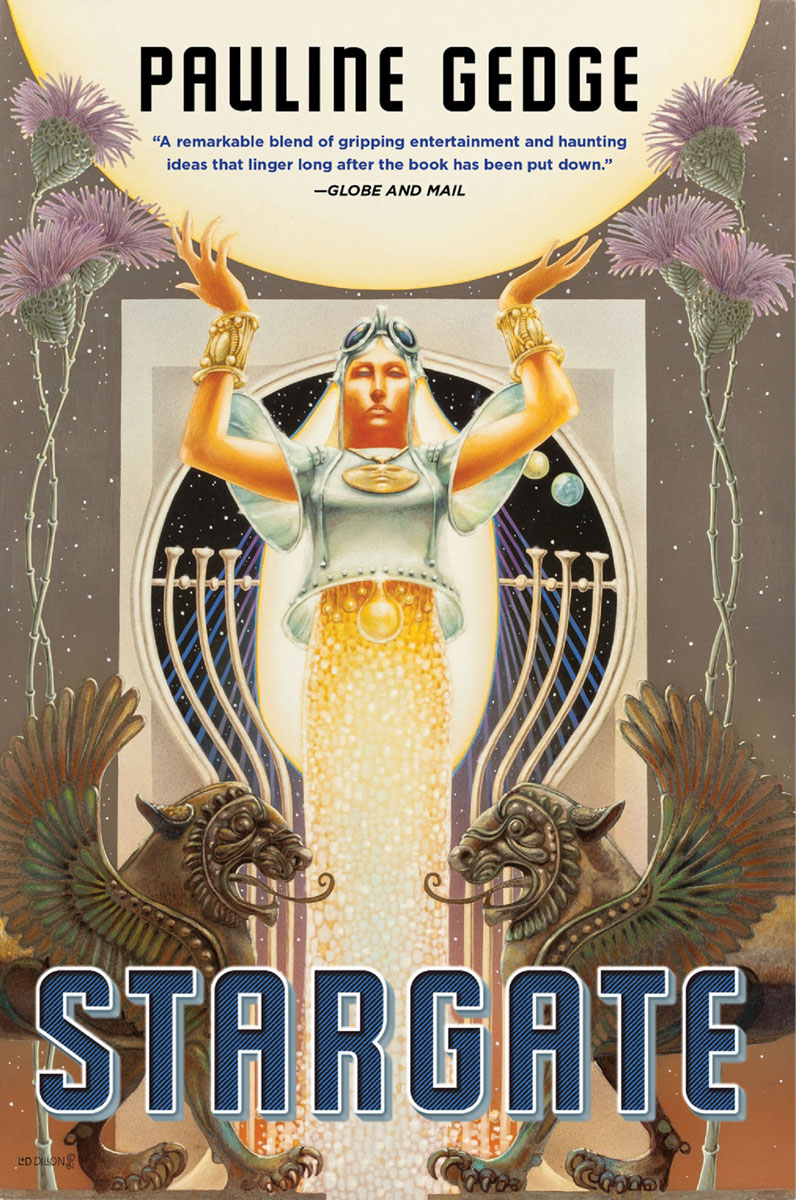

Stargate

Authors: Pauline Gedge

A

LSO BY

P

AULINE

G

EDGE

Child of the Morning

The Eagle and the Raven

The Twelfth Transforming

Scroll of Saqqara (Mirage)

The Covenant

House of Dreams (Lady of Reeds)

House of Illusions

Lords of the Two Lands trilogy:

The Hippopotamus Marsh

The Oasis

The Horus Road

The King's Man trilogy:

The Twice Born

Seer of Egypt

The King's Man

Copyright © 1982 by Pauline Gedge

All rights reserved

Published in 2016 by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-508-4

Cover design: Jonathan Hahn

Cover artwork: © Leo and Diane Dillon

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For

Elisabeth, my sister and my friend.

With love.

Thank you, M.R.S.

1

Ixelion stepped under the archway of his Gate, the box clutched tightly in his hand, and the guards with their silver wands and stiff capes of scales greeted him with soft, deferential voices. He smiled at them briefly and absently, passing them to walk quickly along the causeway, lit now by the fire that welled up through his pale skin and conjured reflections on the mottled surface of the river that flowed through the tunnel. Ixel the fair, he thought with a burgeoning relief. Ixel the pure. There is no water in the All like the waters here on my world. I feel as though I have been away on a long journey fraught with terrible dangers and have come home exhausted and changed, but of course that cannot be. You change. I do not. To right and left the rock tunnel curved, throwing back to him the constant low rumble of the flowing water, and as he paced he brushed the familiar wall carvings which invited his fingers to move along them with the same slow, majestic weight of the river itself. He bent and saw his likeness fragmented by the water. He held out a hand in a gesture of reassurance, spreading his fingers to see the delicate, opalescent webbing between them, and then went on until he came to the mouth of the tunnel, where the river foamed out to spread like gray twisted tresses laid upon the flower-burdened earth. Here he sat for a moment, wetting his feet, closing his eyes and inhaling the damp coolness. She thrust it at me, he thought. I did not want to take it. With a shudder of distaste Ixelion opened his eyes and looked down at the pale-blue wood of the box, and its tiny runnels of gold winked back at him his own fire. Not now, he thought, rising. Now I simply wish to go home.

He skirted the massive, motionless forest from out of whose wet trunks and dripping leaves the ever-present mist seeped. He soon could see the pinnacles of his palace, reaching up to be lost in the grayness of the heavy sky. As he came to the ramp over which another river poured he met a group of his people emerging from the forest, nets full of flowers slung over their shoulders. When they saw him, they ran to him, calling with their light, high voices, and he was quickly surrounded by cool, naked bodies and questioning eyes.

“Sun-lord! It is the sun-lord. Ixelion has come back!”

He stood still while they reached to touch him, unconsciously cradling the box in both arms so that they might not brush against it.

“You have been gone for many years, sun-lord,” one of them said when they had all drawn back a little and regarded him. “Look. My son has left the water!”

Ixelion bent and put his hand on the boy's shoulder. “And have you given up chasing the fish entirely,” he asked gravely, “now that you have hung up your tail?”

The boy laughed. “No, sun-lord. The fish gather on the beach outside my house every morning. They would be disappointed if I did not chase them away again.”

“The sun has sulked since you went away,” a woman remarked. “We have not seen his face once.”

Ixelion talked to them a moment longer and made his farewells, and immediately they picked up their nets and left him. He went up the ramp, crossed his terrace, and entered the green dimness of his hall. Water from the room's many fountains splashed into pools that opened one into another and finally spilled out through the doorway, echoing loudly in the ceiling, where mist hung. Through the passageways more water swirled, ankle deep, cool and pale. He crossed his hall, passing under the waterfall that sprinkled down through the balustrades of balconies high above, mounted stairs, and came out at last in a room with one wall open entirely to the roof of the forest and the ocean beyond. The river that ran down the hill on which the palace was built had been diverted in order that it might fill the great square pool that formed most of the floor of the room. It poured down the wall, troubling the otherwise placid surface of the pool, and spilled out on the other side to cascade through the gap in the floor to the hall below. Ixelion paused. There was no sound in all his vast house but the voice of water, dripping, splashing, running, dancing with itself, singing to itself as it moved from spire to floor and so out to meander through the forest. He walked around the pool and stood at the window, so wide that many spans of his arms could not measure it. The sky met the forest, mingled with it, and filtered to the earth as fog. The air was still. No wind ever trembled in the marshes or riffled the oceans of Ixel, and the sun had never shone full on the crystal domes the people lived in or heated their white skins.

“I am back, my brother, I am home,” he said softly to his sun, and for a moment a faint gleam of diffused gold bathed him, pushing down through the gentle rain that had begun to fall, but then the mist closed in again, and Ixelion left the window.

In one corner of the room was a chest made from the pastelled pink, blue, and mauve shells that littered Ixel's beaches. He went to it and raised the lid, placing the box that Falia had forced upon him carefully inside. Tonight I will turn the pages of Fallan's history, he promised himself, caressing the warm, dry haeli wood, his finger tracing its gold veins. Tonight I will go to Falia. And will you also look upon the thing that is forbidden? some other voice in his mind prompted gently. He closed the chest quickly. Going to the pool, he plunged in, swimming from one end to the other and back again, letting the cool, slippery greenness fill his mouth and slide like a loving hand over his skin. He could not forget how Fallan's soil had cringed away from him, the alien, the one who was whole and did not belong in a place of dying and fracture. Falia's touch had sullied him, and he wanted to wash the decay from his body, but Ixel's clear water could not flush the pictures from his mind. At last he left the pool, descended to his hall, and went out under the rain.

He made his way into the forest, his feet sinking into the sopping undergrowth. He shook back his heavy wet hair and raised his face so that the broad, drooping leaves could brush it. As he walked he plucked flowers for Sillix, stars and diamonds, ellipses and crescents and circles that spun from root to petal, spears and threads that wove in and out, flowers like eyes and flowers scaled like fish, all scentless and colorless yet possessing in their multiplicity of shape an unexcelled beauty. They grew everywhere: on the trunks of the trees, on the ground, in the bosoms of the rivers, where they clung, drowned, to the mud and stone of the beds. Ixelion knew that Sillix had no need of flowers, but it was a politeness, a gesture he would welcome.

He came out of the forest and walked along the ocean, its beach the only place where nothing grew, stepping over crabs and streamers of black seaweed. Out of the translucent crystal domes lining the beach the people came, the children running to hold his hand, the adults waving and greeting him, their round, pupilless eyes bright.

“Sun-lord!” they called. “Ixel has no soul when you are gone. Welcome home! Did you see a Messenger while you traveled? One came for Grenix, and Lanix has also taken his last journey through the Gate. Has the Worldmaker made anything new?” They were as avid for news as ever, and though he called answers to them as he passed their doors, the last question he ignored. The Worldmaker would never again make anything new. He now raged and roared through the universe, bellowing his hatred for all that he had made, flinging his malevolence against the worlds still shining with his first light, and sucking strength from those he had gathered under his fiery black wings. But he will not take Ixel! Ixelion thought fervently as he left the beach and approached Sillix's doorway. Never! Not my gentle, curious people. Only by my death. He stopped on the threshold, stunned. My death? How can I have come to consider such a thing? I cannot die until my sun and I burn away together at the end of time. Suddenly he felt the box of haeli wood in his hands again and with a cry dropped it, but then he looked down and saw that the flowers he had picked lay scattered over his feet. Bending, he gathered them up, and Sillix appeared, bowing gravely.

“So you have returned, sun-lord.” He smiled. “That is very good. Enter.”

Ixelion preceded him and then turned, laying the flowers in his arms. “I did not bring you a gift from another world this time, Sillix,” he said. “I have not been in places where there is happiness.”

Sillix's brow furrowed. “Are there places without laughter, Ixelion? How strange that the Worldmaker should have made beings that do not laugh. I thank you for the flowers. The gift of your presence would have been enough. Please sit.”

Sillix's home was one room made of green-tinted crystal that had been hewn out of the rock on Lix and polished to the smoothness of glass. Just outside the doorway was a small fire pit where Sillix cooked his fish and seaweed. A row of windows ran around the dome close to the ground, and within, under the windows, a circular seat, so that the occupant of the house could sit wherever he would and always be able to look out upon ocean, river, or forest. Mist blurred the upper reaches of the dome. There was no bed, for the people of Ixel slept under the surface of ocean or river, where they were born and where they spent the first ten years of their long lives.

Ixelion sat on the window seat, but Sillix folded his long legs and sank to the floor, tucking his webbed feet beneath him, his eyes on his lord. There was something different about Ixelion. The sea-green hair dewed with moisture still lay waving on the thin shoulders. The long, delicate body still filled the room with a faint golden light. The eyes still brimmed with the essences of sun, water, and living things. Sillix could not put a name to what he felt emanating from Ixelion, and in the end he mentally shrugged. It has been three years, he thought. I have not seen him in all that time, and of course there has been some change in myself. He can never change. He has sat in this house with all my elders, every one of them since the Worldmaker caused the people of Ixel to be, and he was here alone even before that, master of the waters. Ixelion sensed the quick scrutiny and smiled.

“Are the fish plentiful, Sillix? Do the rivers stay clean and the forests grow?”