Stars of David (34 page)

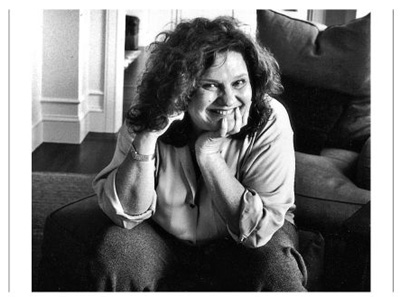

Wendy Wasserstein

WENDY WASSERSTEIN PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1997 BY JILL KREMENTZ

“THE ONLY CONTACT I HAD with people who were not Jews was on the Coney Island bus.” Playwright Wendy Wasserstein is talking to me in her crowded neighborhood Starbucks on the Upper West Side. “There were girls in parochial school uniforms who had plaid skirts rolled up, and I thought they were fantastic. They looked great.”

Wasserstein, the Pulitzer Prizeâwinning author of

The Heidi Chronicles

and

The Sisters Rosensweig

, is a graduate not just of Mount Holyoke College, but Brooklyn's Yeshiva of Flatbush. “For Bruce and me,” she's referring to her brother, Bruce Wasserstein, head of the investment bank Lazard LLC, “the yeshiva looms large. Even my brother, who is not prone to exaggeration or hyperbole like I am, tells me that he still has nightmares about the Kitchen Ladies at the Yeshiva Flatbush.” The Kitchen Ladies, she says, were dissemblers. “As you know, keeping kosher means you can't have milk with meat; so we used to have mock hamburgers, mock frankfurters. I may be eight years old, but I'm smart and I

know

that's not a hamburger and I

know

it's not a hot dog;

don't tell me that it is

.”

She says that, at the age of fifty-five, she still encounters fellow yeshiva alumni around New York City. “The estate lawyer my parents use at Simpson, Thatcher went to the yeshiva. When I was at Holyoke, I would meet people who went nearby to Yale who I remembered from yeshiva who had changed their names. I won't give you their exact names but, for example, suddenly you'd meet a guy at a dance and his name was something like Stanley Stone, and you'd think, âWait a minute; aren't you Shmuel Starkhas?'”

Her childhood alma mater is now called Joel Braverman High Schoolânamed after a rabbi who haunted Wasserstein as a child. “I can remember from second grade, Joel Braverman coming around on Sunday morningsâterrifyingâsaying,

âDid you go to shul yesterday?'

And I hadn't gone because my mother made me go to the Judy Taylor School of the Dance every Saturday instead. And I begged her, I said, âPlease, if you're going to send me to this yeshiva, let me at least go to temple!' I really thought burning bushes were going to come through the window to punish me; I thought the whole family was going to blow up. But she made me go to dancing school instead. My mother had me lying in second grade to that man. Maybe if I had gone to temple I would have become a nice doctor like the rest of the graduates.”

Her mother wasn't religious but harped on Jewish pride. “I remember my mother knocking on the television when someone came on and saying, âHe's one of us.' She told me Barry Goldwater was one of us, and I thought, âNo, he's not.' But she thought his name was Goldwasser and that he was from a department store.”

Wasserstein's father, Morris, a textile manufacturer, made regular contributions to Israel, and Wasserstein remembers being told that the quarters and pennies she sent there would get her name on a tree. Despite her youth, she was skeptical. “Even then I thought, âThere isn't my name on a tree somewhere. There just isn't.'”

But she did absorb her parents' lesson that true altruism was anonymous. “It wasn't about saying, âI want my name on a plaque'; it had nothing to do with that. In fact, we knew there were pish-pish people out thereâor as my mother would say, âthe hoo-hah people,' but we were not them. Definitely not them.”

The “pish-pish” people still seem to piss her off: She's eager to remind them that all Jews are equal in the eyes of an anti-Semite. “The ones who pretend they're Episcopalians because they're chicer than you are, because they're classyâthe fanciest Jews whose children are named âBrooke'âto those people, I want to say, âListen, honey: When push comes to shove, you're Jewish and so am I, and that's the bottom line, kid.'”

When there's a Jew in the eye of a scandal, she doesn't wince for The Jews. “With Monica Lewinsky, there was a part of me that thought, âFinally! A chubby Jewish girl is looked at as a sex object!'”

How much Jewishness would she say is in her work? A critic in London once implied there's too much.

The Heidi Chronicles

was called “too New York,” Wasserstein told the

London Times

,

“The only thing âtoo New

York' about Heidi is maybe my last name.”

But Wasserstein is unquestionably held up as a quintessential Jewish voice in the American theater. In her early play,

Uncommon Women and

Others

, the main character, Holly Kaplan, was the only Jew in her clique at WASP-heavy Mount Holyoke. The main character in

Isn't It Romantic

, Janie Blumberg, rejects the Jewish doctor her parents want her to marry. And Wasserstein has described the three siblings in

The Sisters Rosensweig

as “a self-loathing Jew, a practicing Jew, and a wandering Jew.”

Wasserstein acknowledges that her characters are products of her childhood. “You know, after my friend [playwright] Martin Sherman saw

The

Sisters Rosensweig

, he said, âThis is about people you knew when you were eight years old!' And I thought, âHe's correct! Like the character of Merv, the faux-furrier, for instance: I actually don't hang out with a lot of furriers, but my father was in the garment business, and that guy and the world of that guy, the warmth of that guy, the decency of him, comes from a different time to me.”

I ask if she associates Jews with that kind of warmth or feels an intuitive connection with other Jews. “It depends,” she responds. “When I'm around people who clearly think, âI'm Jewier than you are because I separate the milk from the meat and I have a better sukkah than you,' I can't bear that.” Wasserstein refers to the makeshift outdoor shelter constructed in honor of Sukkot, a harvest holiday. “On the other hand, yes, I do think there's a warmth, there's an irony, and there's that ability in some waysâ in the good tribal wayâto look at others as family. So there's an inclusiveness. I sent my daughter to the Y for a reason.” The 92nd Street Y nursery school, which her daughter, Lucy Jane, attends at the time we talk, offers a kind of preparatory Jewish education. “I thought Lucy might as well know this heritage, and later she can choose whatever.'” Wasserstein gave birth when she was forty-eight and is raising Lucy Jane as a single mother.

She's also upholding the family tradition of “taking in a show.” “Not all religions or societies actually have the respect for the arts that the Jewish culture does,” she says, sipping her hot drink. “On Saturdays, my parents would take me to the theater. That's what you did. And my parents gave me dancing lessons. And these were not pretentious people in any way, it was just their values.”

Those values also included marriage at a young age, which Wasserstein has defied every year she's stayed single. Wasserstein told the

Los Angeles

Jewish Journal

that “I am a walking

shanda

”âa disgraceâand that, when she graduated from Holyoke and the Yale School of Drama without a marriage prospect, her parents called her on the phone to sing “Sunrise, Sunset.”

How important is her Jewishness? “I guess it does define my character,” she says. “I'm not a religious Jew, but my sister died recently, and you do, at those times, look for spiritual love. My daughter was born premature and was in the NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] at Mount Sinai. When Lucy was in the hospital, I called all my Catholic friends, all my New Age friends, I went to Temple Emanu-El, I just thought, âWendy, you've just got to hit all the bases here.' I called Chris Durang [a fellow playwright whom she met at Yale Drama School]âhe's in touch with all the New Age craziesâand I said, âCall them. Get the crystals buried in the ground, whatever they do, just tell them to help.'”

While Lucy's first days felt so precarious, did being Jewish matter? “Well, yes it did because I was at

Mount Sinai Hospital

during the

High Holy

Days

. I had Jane Rosenthal [who runs a film company with Robert DeNiro] bringing me her mother's brisket in the hospital room. So in some ways yes, because that was a Jewish hospital and it was the Jewish New Year and there was my friend Jane with brisket.”

Lucy survived and thrived and Wasserstein has carted her to Broadway shows ever since. I ask if she's talked to Lucy about being Jewish. “I've brought it up,” she says with a nod. “We celebrate everythingâHanukkah, Christmas, Valentine's Day. Just recently, we celebrated the cleaning lady getting married.”

She has no problem celebrating Christmas even though her family never did (“We went to Miami instead”), but then she recoils when I ask if she gets a tree. “That I couldn't do, no,” she says with a shudder. “I would think flying hams would come into my house if a tree was there.”

One of Wasserstein's most successful plays,

The Sisters Rosensweig

, features perhaps her most overtly Jewish characters. Sara, the oldestâ originally played by Jane Alexanderâis living in London (as Wasserstein did for a while) and downplays her Jewishness; the middle sister, Gorgeous Teitelbaumâplayed originally by Madeline Kahnâis a gregarious president of the Jewish Sisterhood in Newton, Massachusetts, who lusts after Ferragamo shoes and constantly quotes her temple rabbi; and Pfeni, played by Frances McDormand, is a single, socially conscious travel writer. When the oldest sister, Sara, rebuffs the advances of Merv Kantâthe visiting Jewish furrier from Brooklynâhe challenges her:

MERV: I don't understand what's so wrong with you, Sara. I like you.

SARA: Your world is very different from mine.

MERV: No, it's not. I changed my name from Kantlowitz, and my daughter, the Israeli captain, went to St. Paul's. And where did you come from, Sara?

SARA: Don't proselytize me, Merv.

MERV: Sara, you're an American Jewish woman living in London, working for a Chinese Hong Kong bank, and taking weekends at a Polish resort with a daughter who's running off to Lithuania!

SARA: And who are you? My knight in shining armor? The furrier who came to dinner. Why won't you give up, Merv? I'm a cold, bitter woman who's turned her back on her family, her religion, and her country! And I held so much in. I harbored so much guilt that it all made me ill and capsized in my ovaries. Isn't that the way the old assimilated story goes?

Wasserstein says

Rosensweig

played very differently in Israel than it did in New York. “It was performed in Hebrew, and I actually remembered enough Hebrew that I could tell it wasn't such a great production,” she says. “Because the central issue in the

Sisters Rosensweig

was about identity, and in Israel they

know

they're Jewish.”

She does worry about Israel and whether “the world really cares” that it survives. “I think that part of the world believes that if we could just move the country to Iceland or Pluto, it would be a lot easier. Or to Martha's Vineyard. That would be really nice because all the Jews would be happy and a lot of them have homes there because they're pretending that they're actually Episcopalian, so it would work out nicely. And Bill Clinton could come and play golf and everyone could shop.”

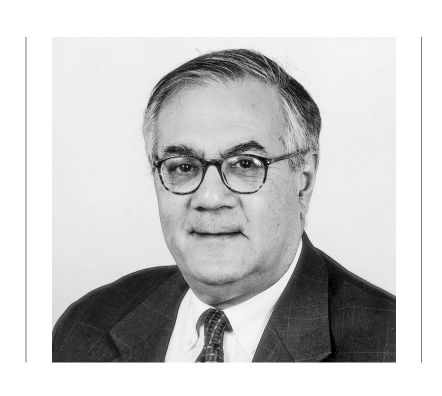

Barney Frank

BARNEY FRANK, who has represented Massachusetts in the U.S. House of Representatives since 1981, told the

New York Times

back in 1996 that he's never been in the majority: “I'm a left-handed, gay Jew.”

We meet over his large desk in his congressional office with its cranberry-colored carpeting. “Being Jewish made me feel like an outsider,” Frank says, “but so did being gay. In my case, remember, you can't really separate out the two; and in fact, by being gay, it made me even more of an outsider, because I was an outsider even among Jews. But I think it left me better prepared to be a minority than a lot of people. I was used to it.”

At sixty-five, Frank has a bit of a paunch and a little more salt in his salt-and-pepper hair, but he still retains his trademark machine gun delivery and doesn't spend a lot of time on questions he deems unworthy of reflection.

For instance, how has he reconciled Judaism and being gay? “There's nothing to reconcile,” Frank shoots back. “They are both facts of my life. What's to reconcile?” Well, for example, the fact that he's a homosexual and that the Torahâin Leviticusâcalls homosexuality an “abhorrence.” “Well, I don't keep kosher. I eat lobster. I eat shrimp. They're all in Leviticus. I don't have a strong theological sense. I do not observe Shabbat. I don't sit around worrying about how I reconcile driving on Saturday afternoon.”

Frank grew up in a “very Jewish” family that was loosely observant. “If I were ever eating bacon when my grandmother came, out of respect, we would put it away.”

His parents talked to him about identity. “My father, especially, was wary of Christian society,” says Frank. “I was born in 1940, so I can remember in 1947, 1948, we had a little box for the Jewish National Fund and a âBoycott Britain' bumper sticker on the car.”

Frank associates altruism and tolerance with his Jewish upbringing. “My father had a truck stop, and it was the only one in the forties and fifties where blacks were allowed to sleep overnight. I was very proud of that.”

Today, Frank doesn't fast on Yom Kippur, but he doesn't go to the office either. “On Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I will not go out of the house, because I think that reflects badly. So even if I don't go to temple, I will not do anything that would undercut the ability of other Jews to be totally observant. So my schedulers know that on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I will not be doing anything.”

He doesn't celebrate Christmas. “Actually I go to a Hanukkah party every year run by Cokie Roberts.” (Roberts is a senior news analyst for NPR and used to cohost ABC News' Sunday morning show.) “Cokie, who is herself very Catholicâhas a husband, Stephen Roberts, who is Jewish,” Frank explains. “And she invites all her Jewish friends. Talk about intermarriage: For years, the only all-Jewish couple at Cokie's Hanukkah party would be me and Herbâmy ex-lover.”

I ask if he gravitates socially toward other Jews. “I do. Not consciously, but a disproportionate number of my friends are Jewish. Obviously there are connections based on common backgrounds. Now that's less so with my gay friends. But with friends my own age, more of them are Jewish.”

Does the same go for his romantic relationships? “It's not been a factor,” Frank replies. “I've had two relationshipsâone for eleven years with a Jewish man and I'm now dating a Columbian who's Catholic.”

His siblings married non-Jews, but they're raising their children to be Jewish. “I'm glad that they are,” says Frank, whose only personal effects in his office are photographs of his nieces and nephews and a handwritten sign from one of them: “UNCLE BARNEY'S DESK”âwith the S's written backward. “My brother's divorced. He just remarried a woman whose parents are Orthodox, and my mother was told about the dress code for the wedding: no cleavage and no pants suits. She said, âAt ninety, it's very flattering to be told not to be sexy.' The invitation also said the men will dance with men, the women dance with women. I showed it to my boyfriend and said, âSee, you've got to dance with me or the rabbi will be upset.'”

When the congressman is in synagogue for a wedding or for the High Holy Days, he does feel some emotional tug: “It happens anytime I put on a tallis and yarmulke.” He reads Hebrew but doesn't understand it. “Last time I was in IsraelâI think I was with Gay Israelisâone of them told me that I read Hebrew with a Yiddish accent.” He picks up an Israeli newspaper. “Look at this.” He shows me. “It's a big article about me being gay. I can read it, but I don't know what it says.” He zeroes in on one sentence. “I can read this: It says, âDick Cheney,

abba

'âthat means âfather'ââ

shel

'â that means âof'ââlesbian.'” He smiles.

I ask if Frank has ever drawn on his religion when he was in trouble. I'm obviously thinking of the low point in his career, in 1990, when he was censured by Congress for paying a male prostitute for sex and helping him get thirty-three parking tickets dismissed. “No,” Frank answers. “I think Judaism is important and that it does not survive without a strong religious component, but personally I'm just not religious. To the extent that I am consciously in charge of myself, I'm very rational. My view is that you've got to

think

your way through things.”

When he mulled the notion of a political career decades ago, he believed his ethnicity would prevent him from having one. “I thought being Jewish would keep me from being elected,” he says. “When I was growing up, there were very few Jews in elective office. Today, I've seen political anti-Semitism largely crumble. Being Jewish is just not a factor anymore.”

Frank once said that he didn't reveal his sexuality when he was first elected to Congress (he came out publicly in 1987), but he couldn't hide his religion. “I outed myself with a bar mitzvah,” he told the

Washington

Post

in 1998. “It was too late to be in the closet as a Jew.”

I have to ask about the time his colleague Representative Dick Armey from Texas called him “Barney Fag”âallegedly thanks to a slip of the tongue: Does Frank agree with

New York Times

writer Frank Rich's comment at the time that had the slur been “Barney Kike,” there would have been more of an outcry? “Of course,” Frank answers. “I think it's a paradox in America: Anti-Semitism, I think, is pretty much verboten; only crazy people are anti-Semitic. So yes, calling someone âkike' would be totally destructive. With regard to race and homophobia, it's an interesting thing: I think the country is, in fact, more racist than it is homophobic, but that we are

officially

anti-racist. I think the average American is not anti-gay but thinks he's supposed to be; and he's probably more racist than he's willing to admit.”

Our conversation takes place just as Senator Joe Lieberman is poised to launch his candidacy for 2004, and I'm curious to know Frank's feelings about the way Lieberman dealt with his Jewishness in the last campaign. “Basically very well,” Frank replies, but then goes on to criticize him. “I disagree with the suggestion that being religious makes you better in some ways than othersâand that sometimes creeps in. There's a kind of triumphalism, but it's not specific to Joe's Judaism; you had it in Carter, you have it in Bush. But in general, I thought Joe handled it very well. I was very pleased when Al nominated him; I thought it was good for Gore, good for the Jews, good for America.”

So Frank never thought Lieberman was overdoing his devoutness? “I have spoken to him generally about using religion as a vote-getter. I think that's a mistake. I don't think religiosity should be a basis for getting votes.”

Is America ready for a Jewish president? “No,” Frank says. “The presidency is unique. I think we've gotten rid of anti-Semitism everywhere but the presidency. You know, for all of the to-do over John Kennedy, he's still the only non-Protestant to be president of the United States. The presidency is sui generisâfor blacks, for gays, for Jews, for women. And that will always be the case.”

I still don't have a clear picture of where Frank's Jewish identity falls on the spectrum. “Oh, it's very important,” he says. “Empirically it's very important. When I'm asked what I care about in politics, the moral values that I'm looking for are alleviating poverty, fighting discrimination, and protecting freedom of expression. And I think being Jewish has a lot to do with all of those.”

So if ritual is absent, how would he characterize what being Jewish is about? “It's the common history of having been discriminated against, having relatives who were killed in the Holocaust. It's the experience of being unfairly treated because of who you are. That's one of the reasons that I think Jews are as supportive on gay rights as they are. Being Jewish is also about the tradition of intellectual activityâthe life of the mind. Appreciation of food. By the way, I have a great story about that: I was in Berkeley, California, with my college roommate, who lives there now. And he's Jewish, and we went out to a restaurant for lunch, and the waitress came over and said, âDo you want to know the specials?' We said, âYes, we do.' She said, âWell, the special soup is puree of beets with crème fraîche.'” Frank chuckles. “You know what that soup was?”

Borscht?

“Yes! With sour cream!” He laughs. “I said to my friend, âCharlie, that's

borscht with sour cream

!' Being Jewish is about shared experience, but it's also survival in the face of oppression, commitment to the enlightenment of the intellect,” and of course it's communion over a bowl of beet soup.

Or a plate of mandelbread. Apparently, it's one of the congressman's favorites, and when the organization PFLAGâParents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gaysâasked Frank's mother to contribute to their cook-book, she e-mailed them her recipe for mandelbread, a Jewish dessert that resembles biscotti. Elsie Frank did more than bake for her son: She made speeches on his behalf when he was running for office and was corralled into making a campaign ad in 1982, in which she said:

“How do I know he'll

protect Social Security? Because I'm his mother.”