Stars of David (9 page)

“She wrote this article in

The New Yorker

without having seen the show,” Portman says. (Ozick wrote that Portman's characterization of Anne Frank in a

New York Times

interview was “shallowly upbeat.”) “She said the most important line that's been taken out of Anne Frank's diary,

âIn spite of

everything, I still believe people are good at heart,'

is how Anne Frank has been interpreted, when in fact she was miserable and had this awful life that has sort of been distorted to make her a martyr. [Ozick wrote that Frank's story has been âkitschified.'] She quoted me out of context from an interview where I was saying that I wanted to bring âlight' to the character.

“But Anne Frank was a twelve-year-old girl; and when I met with Miep [Miep Gies, Anne Frank's father's secretary] and Bernd Elias, her first cousin who is her only living relative, they both told me that she was this hyperactive girl, happy, always running around, they were always yelling at her to slow down and be quiet because they were in hiding; when Miep would come to the house, she would run up to her and always be asking her questions and touching her. So I had this image in my head of the energetic young girl who obviously is put in the most awful situation and creates this world for herself through her writing. It was important for me not to make it The Death-And-Dread Show because everyone knows that even in the most horrific circumstances, there's some sort of life and some sort of humor.

“Anyway, Ozick said I said Anne Frank âwas happy' or something that sounded moronic. [Portman told the

Times

that Anne Frank's diary is “funny, it's hopeful, and she's a happy person.”] And then she continued to lecture about it, including at my own university, basically portraying me as this moron and my interpretation of the diaries as completely disrespectful to Anne Frank, which was the last thing I would ever do. None of us know what her life was like or who she was; we can only do as much as we can read, study, and imagine. I don't expect not to be criticized because that's what I do, I put myself out there to be criticized, but I thought it was unfair.”

I wonder how personally Portman connected to the character. “Very personally,” she says. “Because my grandparents didn't talk about those years much, especially my grandfather. His younger brother, who was fourteen at the time, was in hiding from the Nazis and couldn't take it one more day and ran out and was shot in the streets. And his parents were killed at Auschwitz. He was the one I'd always related to in the family. He was sort of the quiet, brilliant man who led Pesach and I would always imagine him or his father in these horrifying humiliating conditions. The humiliation is almost harder for me to imagine than the physical pain. To think about such dignified people.”

She was also surprised to discover how timeless and universal were Anne Frank's fixations. “She talked about crushes and sex and genitals and all of these things that I was thinking aboutâand embarrassed to be thinking aboutâwhen I read the diary for the first time at twelve years old. I thought I was weird and crazy, and then you read this diary and it's not some grown-up's book written for kids, like âWhat's Happening to My Body?'; it's another twelve- or thirteen-year-old telling you what they're going through.”

When it comes to Portman's own romantic life, it has obviously been a staple of gossip columns (she's been linked to actors Lukas Haas and Hay-den Christensen, and to rock star Adam Levine), but she says she's not necessarily looking for a Jewish husband. “A priority for me is definitely that I'd like to raise my kids Jewish, but the ultimate thing is just to have someone who is a good person and who is a partner. It's certainly not my priority.” She says her parents don't push her one way or another. “My dad always makes this stupid joke with my new boyfriend, who is not Jewish. He says, âIt's just a simple operation.'” She laughs. “They've always said to me that they mainly want me to be happy and that's the most important thing, but they've also said that if you marry someone with the same religion, it's one less thing to fight about. But according to that argument, I might as well only date vegetarian guys. The term âintermarry' is sort of a racist term. I don't really believe in purity of blood or anything like that; I think that's awful.”

She doesn't think it necessarily takes two Jews to maintain Jewish continuity in a family. “I feel the strength to carry that on myself. It's obviously easier when both parents are in it together, but I don't necessarily think it has to be. I always think that if a guy I date is Jewish, it's a plus, but it's not one of the reasons I would like him.”

Portman says she resists any kind of blind tribalism. “I don't believe in going along with anything without questioning. I think that's the basis of Judaism: questioning and skepticism.” She says that for her, basic humanity comes before faith. “To me, the most important concept in Judaism is that you can break any law of Judaism to save a human life. I think that's the most important thing. Which means to me that humans are more important than Jews are to me. Or than being Jewish is to me.”

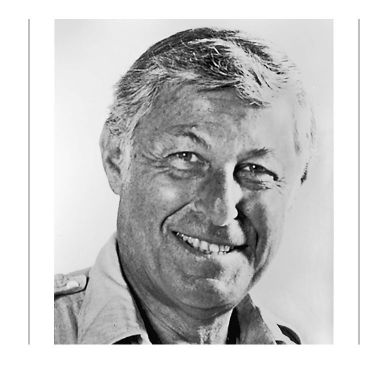

Don Hewitt

TO WORK FOR 60 MINUTES creator and executive producer Don Hewitt, which I did for six years as a producer, was to work alongside an inimitable character who seemed quintessentially Jewish. Don's manic energyâhis hopping up and down about stories that grabbed him, his undisguised dismay at stories that didn't, the way he'd yell “Hi honey!” when he charged by you, or repeat the same joke he'd heard to every person he encountered in the hallway, the way he'd exhort you to get an interview or give you a wink when you “did good”; his Brooklyn lilt, his histrionics, his dated fashion sense, his unflashy routineâmade him feel familial to me despite his eminence within CBS. He was a cheerleading but demanding Jewish uncle.

But in the strict sense, Don couldn't have been less of a Jew. He observed no holidays (one could always find him at work on Yom Kippur), and he demonstrated zero emotional connection to Jewish identity. “I've always felt more American than Jewish,” he says, sitting behind his desk in his trademark camel turtleneck, snug tweed blazerâhandkerchief peeking from the pocket. “Let me put it this way: Am I proud to be Jewish? Not particularly. Am I

happy

to be Jewish? Yes! Because I think somewhere somehow it gave me the impetus to be ambitious. I'm proud of what I did at

60 Minutes

, but I'm not proud of being Jewish. I'm

happy

about it. I think being Jewish is

nifty

. And mostly I'm Jewish by temperament.” What does he mean by that? (I have my own ideas.) “I like Jewish food, I like Jewish humor, I like Jewish people. But I'm more at home with nonbelieving anybody, including nonbelieving Jews. I've always taken to the nonbelievers.”

He grew up in New Rochelle, the child of Frieda, a German Jew, and Ely, a Russian Jew. “I stayed home from school Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, but at Christmas I got Christmas presents. I was confirmed at a Reform temple called Temple Israel mostly because that was the social thing to do in that town. My mother was a little bit snobbish about the people who belonged to the Orthodox or Conservative synagogue. It was not exactly âfeh,' but it approached it.” He chuckles.

His phone rings and he answers it. “I think you have the wrong number.” (Don often picked up his own line.) He continues: “I never felt really discriminated against, but there was always that undertone that you

could

be. I think that steeled you. I think Jews who have made it in America made it to kind of show their gentile neighbors, âWe're made of pretty steely stuff, and nothing is going to hold us down.' I think my being Jewish probably was a catalystâit helped me develop the kind of drive that Jews have to be successful. But I never related it to Torahs or yarmulkes or tallises. I always considered those things to be tribal rites. When I used to go to the movies as a kid and I would see people dancing around a fire with gourds in tribal ceremony, I'd think, âJesus, that's what they do in synagogue!' I used to sit in temple all the time and listen to these Reform rabbisâ” He puts on a Britishy, pretentious accent with great bravado: “â

On this holiest of holies, the Yom Kippur commences

. . .' and I'm thinking, âWhere the heck did you learn to talk like that? Who talks that way?'”

Hewitt, eighty-three, orders lunch for us by shouting to his assistant to call up Teriyaki Boy. “Bev!” he bellows to Beverly. “Can we get some sushi?”

He goes on: “My grandfather changed his name from Hurwitz to Hewitt long before I was born. In fact, we used to kid around in the family because they said my grandfather wanted to change his name to Hurley, which is Irish. My aunt tells this great story of being at my confirmation with all the kids' names printed in the program, and overhearing one woman say, âDonald Shepherd Hewitt? How did

he

get in here?'”

I ask him if there's ever been a time when he turned to some kind of faith. “No. I don't have any faith. As a kid, when it would rain so hard that there'd be a flood, I used to say facetiously, âHow smart can God be?

I

know enough to turn the water off in the shower.

Turn the water off!!

What's the big deal?'

“I used to go out with a Catholic girl when I was a kid. And we used to argue about religion, because I had none. And one day she said to me, âYou've got to admit that the Easter service at St. Patrick's Cathedral is beautiful.' And I said, âI will admit that Easter service at St. Patrick's Cathedral is beautiful, if

you

will admit that Radio City Music Hall does it better.'” He laughs. “It's

theater

. The chanting, the cantors; it's a performance. And I don't fault anybody who gets something out of it. I don't. The only thing I ever prayed for was a parking space.

“Let me put it this way: If there is a God, a supreme being who created the universe, that's got to be a pretty magnificent entity; I can't believe that anyone so great as to have created life could give a damn whether I worship him or not. Wanting to be worshipped is a human failing. I can't ascribe that to a supreme being. If there is one, why would he care whether I paid homage to him? He's bigger than that. Do you think he's sitting around all day, thinking, âDon didn't pray today' ? I think the last time I was in a synagogue was for [violinist] Itzhak Perlman's kid's bar mitzvah.”

Hewitt says his three kids (by his second marriage) weren't raised with religion, but most of their friends happen to be Jews. He chalks that up to childhood summers spent in Fair Harbor, Fire Island. “They just fell in with a bunch of Jewish kids from Fair Harbor,” he says. Would his children call themselves Jewish? “I don't think they call themselves anything.

I

don't call myself anything.”

He concedes that his third and current wife, Marilyn Berger, whom he married in 1979, might be more observant if it weren't for the man she chose. “I have a feeling that if Marilyn were married to a religious Jew, she would be more involved,” Hewitt muses. Marilyn still lights candles for her sistersâthe

yartzeit

candles. I look at them and to me, it's like tribal rites again.”

Does it give him pause at all that the Jewish line might have stopped with him? “No, no. I have to believe that the world would probably be betterâ” He's interrupted by lunch arriving. “Thank you, darling,” he tells another assistant. (Bev's stepped out.) “Did you tip the guy?” When he looks at the tuna rolls, it's clear they've combined our orders in one plastic container. “We'll eat from the same plate,” he announces, pushing the sushi my way so I can reach it. “Here's some napkins.” As he chews and talks, he keeps encouraging me, like a Jewish mother, to eat. “Here, there's more here, honey.”

Back to continuity: “I think it's a better world if everybody's integrated,” he says, mouth full. “There are Jews who get horrified because a Jew marries out of their religion, and a lot of them are very liberal people who think it's great when there are inter

racial

marriages.”

Since Hewitt covered World War II as a London-based war correspondent for

Stars and Stripes

, I wonder how he relates to what happened to Jews during that time. “It's terrible,” he says. “I don't think you have to be Jewish to be horrified at the Holocaust. You don't have to be black to be horrified by lynching.”

He feels that Jewish interests have been hurt by Jews who say their suffering surpasses all others'. “I once said to Steven Spielberg, âYou would do your cause a lot better if you would acknowledge that the Jews weren't the only ones who ever suffered a holocaust. And then he did that movie about the slave ship [

Amistad

]. Which was lousy, but he did it right after we had that conversation. We cannot go on believing that nobody else had

tsuris

but us. There are a lot of people. There are a lot of blacks who say âHolocaust, shmolocaust; we got lynched!' And they're right!”

Does he think he brings any of his Jewishness to his news judgment? “Yeah, but not consciously. I think what I bring Jewish is called

seckel

[a Yiddishism for “brains, savvy”]. Jews have got

seckel

. I think that's what I bring.”

Hewitt's Jewish credentials were harshly called into question when

60

Minutes

did several stories in the seventies and eighties that were perceived as overly sympathetic to the Arab point of view. There was a deluge of protest in 1975, for example, when Mike Wallace reported that Syrian Jews weren't as oppressed as had been previously believed. The criticism from some in the Jewish community culminated in Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg, then president of the American Jewish Congress, requesting a face-to-face meeting with Hewitt and Wallace in their CBS offices. Hewitt says Hertzberg went after him subtly but personally. “The son of a bitch,” Hewitt recalls, “he came over here to see me and he sat in my office and he said, âHewitt . . . Hewitt . . . ; there's got to be a

Horowitz

under there somewhere.'” Hewitt smiles. “I said to myself, âYou son of a bitch; you come here for a peace meeting and you make trouble.'

“Now the other hysteria was when we did the Temple Mount massacre.” He's referring to Wallace's 1990 story recounting the killing and wounding of Palestinians by Israeli soldiers at Jerusalem's sacred Temple Mount. The Anti-Defamation League was up in arms, charging that the broadcast “failed to meet acceptable journalistic standards” and that Wallace “gave the false impression that Israel is engaged in a deliberate cover-up.” ThenâCBS president Larry Tisch, a prominent Jewish figure in New York society, got involved. “Larry went ape about this story,” Hewitt says. “I was portrayed as a self-hating Jew and I said to him, âYou've never met a more self-loving Jew in your life! I don't hate myself! Secondly, if I did, it would not be because I was Jewish.'” But the personal attacks clearly left their mark. “I remembered that for a long time,” Hewitt says.

There were other slights. “I remember going to a cocktail party given for the new chairman of RCAâI can't remember his nameâand when Larry Tisch came in, I said, âHey boss, how are you?' And he said, âDon't you

Hey boss

me,' and he walked away. And I left and got in a taxiâit was at the River Houseâand I came here to CBS and went into David Burke's office [then president of CBS News], and I said, âDavid, I resign.' He said, âWhat do you mean?' I said, âI don't want to work here anymore. I just got cut off at the knees by Tisch because of a story we did.' And Burke calmed it all down . . . But it was a tough time.”

Another snub: “I went to a party once at Werner LeRoy's [the flamboyant restaurateur], and I got attacked by Mort Zuckerman [real estate and publishing magnate] and Barbara Walters, who said, âHow could you do that story at this terrible time in Israel's history?' And I said, âHow about the stories we did at the terrible time in America's history in Vietnam? Were you worried about

that

?' I was shocked. And I said, âI get accused of being a self-hating Jew because I'm critical of Menachem Begin. Nobody ever called me a self-hating American because I was critical of Richard Nixon.' There's a

thing

about Jewishness . . .” He trails off. “Right now the Jews are too big and too smart to cave in to this feeling that we are victims in the Middle East. They're not really victims in the Middle East.”

Hewitt heralds the fact that Abraham Foxman, National Director of the Anti-Defamation League, ultimately wrote him a letter apologizing for the ADL's outcry over the Temple Mount story. “He saidâI'm just paraphrasing hereââNow the verdict is in: It looks like it happened a lot closer to the way you guys said it happened than the government said it happened, and we owe you an apology and I invite you to use this letter any way you want.'”