Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours (14 page)

Read Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours Online

Authors: Marc Nager,Clint Nelsen,Franck Nouyrigat

Why is it so important to entrepreneurs to move

fast

? Startup Weekend imposes strict time constraints because there are time constraints in the real world, too. People have day jobs, families, or both. They can't take an infinite amount of time with an idea. You don't want your great idea to be outdated—or accomplished by someone else—by the time you decide to do something about it.

It is not necessarily that speed will equal success; however, moving more quickly

will

let you get to success faster. You need to recognize when you are succeeding and when you are failing. That is, the more ideas you try as an entrepreneur—different products, audiences, monetization strategies, site designs, and so on—the more you will learn. People fail multiple times each weekend, and that's okay.

For example, we once heard a pitch on a Friday night for something called Hoy Hoy, a site that would help people in developing countries use an SMS (text) system and electronic banking to pay each other. In areas where there are few banks and people don't have access to a lot of paper currency (or it's dangerous to carry around too much), this system would give people another option.

By the time we caught up with them on Saturday afternoon, the team's ideas had undergone two more iterations. First, they decided to work instead on the idea of a group savings account. For example, let's say that you and your roommates wanted to save up for a television or a trip. This would be a way to do it. They discussed this idea for a while, trying to determine how the money would be managed. Would one person get to be in control of the money and act as a sort of administrator, or would everyone be in control of their own money? What if someone wasn't meeting a savings goal? Would they be able to default for a month or borrow money against what they had already submitted? Wouldn't too many disputes about money result? The idea seemed to be growing more complicated.

The next version of their plan was for a site to which people were saving for a group trip, contributed equally, and could only take out their own money. But again, the question arose: Who would pay for this service? This continued to plague the group throughout the course of the weekend. On Sunday, one of the mentors who frequently attends Startup Weekend dropped by and started listening to the team, and immediately recognized a successful market strategy. A friend of hers who runs a travel website had often complained to her that he had no way of figuring out people's intentions when they came to his site. Were they daydreaming about a honeymoon in Hawaii with a husband they had yet to meet? Or were they planning a trip to Denver next week and pricing different options?

When the mentor heard about this team's plan, she immediately grasped the potential. A group of people saving for a trip together and actively putting money aside would be the perfect audience for travel websites. Even if some people backed out or some trips didn't happen, at least you would have a good idea of people's intentions. You could figure out where they wanted to go, how many people were traveling, when they planned to leave, what their budget was—all extremely valuable data. In addition to surveying people at Startup Weekend about whether they would use such a site to plan a trip, the team members also called travel company employees to ask if they would be interested in advertising to the site's users, or actually attaching the site to their own product.

Finding out whether there is a market for your product is a vital part of Startup Weekend; it's something we call

idea validation

. This theory of how to start a business has been around for a long time. Decades ago, it was called

bootstrapping

. Now, it's referred to as developing an

agile

or

customer development

model. We talk more about all of these terms in the next chapter—but whatever you call it, the most important thing to understand about this approach is that it is

not

a traditional business plan.

Instead of forming an elaborate strategy of what the entire product will look like, who the consumers will be, and how much money it's projected to make three years down the line, we recommend starting small and working with the information you can get immediately. For example: Who will want this product tomorrow? We always warn people in their Sunday presentations against predicting some ludicrous amount of revenue five years down the line. No hockey-stick growth curves allowed! There are generally no real justifications for their assumptions, and investors are not particularly interested in these projections anyway. They simply want to see the problem, the solution, and how you will ultimately find and satisfy your customers with your product.

A good place to start is with your immediate circle of friends. Throughout the event, you'll see team members wandering around, asking other people whether they can offer opinions on a product. The aforementioned group that was interested in helping men shop for women found a few females and asked them what kind of gifts they like. They then asked men what kind of help they needed when shopping for the women in their lives.

It's so easy these days to send out a survey to a larger group as well. It's as simple as finding a few relevant questions to ask and posting them on your Facebook page. The Internet-TV application team asked people if they would like to watch TV with their friends in different locations. Some groups announce their product online for potential users to test, or to encourage people to sign up for it when it becomes ready for testing. It's important to get the market's pulse as quickly as possible.

The Three Main Criteria

By Sunday morning, energy levels start to flag. Tension builds on some teams as members have to make tough decisions about how to guarantee that they have a viable presentation to give by 5 PM. If there is ever a time for the team leader to assert him- or herself, this is it. Boulder Startup Weekend participant Dave Angulo says that he wouldn't compare the team leader role to that of CEO so much as one of “project manager.” He says the important part is “organizing people, understanding where the roadblocks are, making sure you can clear those roadblocks so everyone can keep moving.”

It is actually surprising how seldom we see teams argue over who should be the team leader. Usually, one team per weekend might have a couple of alpha entrepreneurs who both want to take charge, and we occasionally have to intervene. But for the most part, everyone there simply wants to work hard. A lot of them come from environments where they have to deal with a lot of bureaucracy and so they don't relish the idea of organizing other people so much as generating a real product.

Still, it is possible to tell on Sunday night the teams who worked well together—which leaders were overbearing and micromanaging, and which ones let things spin a little out of control. Over the course of doing hundreds of these events, we have tried to focus less on how shiny the pitch decks are on Sunday night, and instead concentrate on what people have made and how they've worked as a team. As Dan Rockwell of Big Kitty Labs told us, “Startup Weekend is focused on action. They care less about the bar chart with thousands of potential dollars and more on other questions like—did you get along with your team?” If you can't figure out how to work well within a team, you could have an idea as great as the next Groupon, and it will crash and burn because you can't get over your ego.

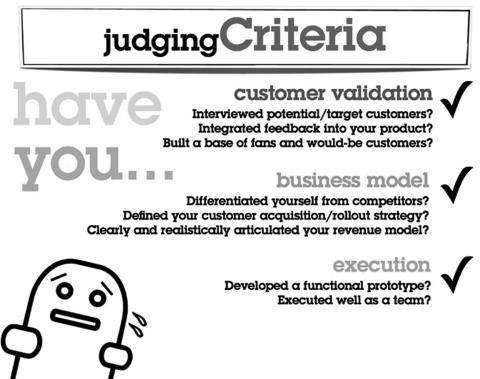

At each Startup Weekend, we try to bring together at least three judges who are experienced in the field of entrepreneurship—either successful startup founders or investors. We ask them to judge the Sunday presentations using three main criteria:

1.

Customer Validation:

Did you interview potential or target customers? Did you integrate that feedback into your products? Have you built a base of fans and would-be customers?

2.

Business Model:

Did you differentiate yourself from your competitors? Did you define your customer acquisition and rollout strategies? Did you clearly and realistically articulate your revenue model?

3.

Execution:

Did you develop a functional prototype? Did you execute it well as a team?

We discuss the first one further in the next chapter on customer development and lean/agile strategies for launching a startup. We do expect teams to show evidence that they have gotten some information from potential customers about what they want.

We should say with regard to criterion 2 that you don't need to go through every other company out there with a similar mission and explain the difference. There may be a number of them. Sometimes judges or members of the audience will ask questions to make sure that you are aware that some of your major competitors do exist. At that point, you can show that you know the market. You have only five minutes during the presentation. (At some Startup Weekends, presentations are even shorter because of the number of teams presenting.) So, you want to spend as much time as possible focusing on your own product.

As we mentioned before, the execution will depend very much on the product. We like participants to have a functioning prototype; however, we realize that this isn't possible in all circumstances. But we do want to come as close as possible to the actual experience users will have with your product. Screenshots of your web page will help, of course. But we still want you to walk us through the

experience

in your presentation.

Even though judges are trying to decide whether you worked well as a team, they do not want to see every one of your team members giving the presentation. Having seven people pass the microphone back and forth wastes time, and looks a lot like a first-grade play. So choose the one or two people with the best stage presence to talk to the audience and the judges. Of course, you want to be sure that they thank the rest of the team in their presentation. (Some people even include a slide in their pitch deck with pictures of their team or at least everyone's name.) When the judges pose questions that the presenter can't answer, they should see if someone else on the team can help.

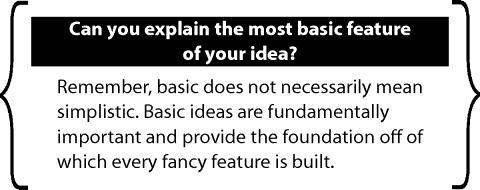

Now that you know the judging criteria, consider what questions you should be answering with your presentation. The following are some questions that Dan at Big Kitty Labs asks about all of his team's prototypes, which are vital questions for Startup Weekend, too:

- What is it?

- Why do I need it?

- What does it do?

- Who uses it?

- How does it make money?

- How does it provide value?

- Who'd write a story about it?

- How does it work?

- What does it rely on?

- What's it like (experience-wise)?

- Where do the data come from?

- What are the barriers, black boxes, and questions you have no idea how to answer yet?