Steampunk: Poe (4 page)

Authors: Zdenko Basic

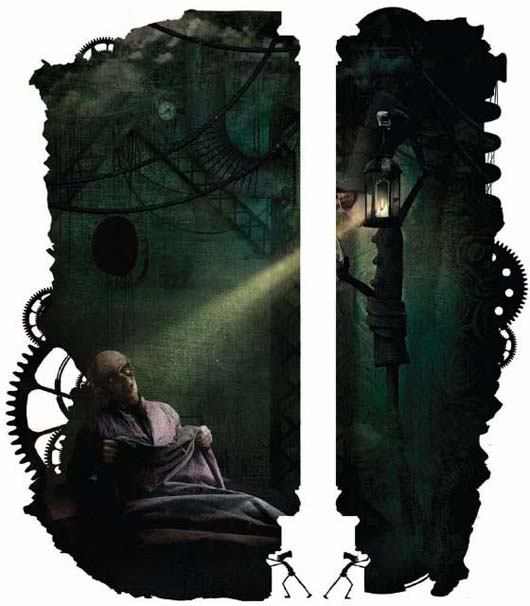

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence. First of all I dismembered the corpse. I cut off the head and the arms and the legs.

I then took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly, so cunningly, that no human eyeânot even

his

âcould have detected any thing wrong. There was nothing to wash outâno stain of any kindâno blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that. A tub had caught allâha! ha!

When I had made an end of these labors, it was four o'clockâstill dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart,âfor what had I

now

to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbor during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises.

I smiled,âfor

what

had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them searchâsearch

well

. I led them, at length, to

his

chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them

here

to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim.

The officers were satisfied. My

manner

had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat, and while I answered cheerily, they chatted familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears; but still they sat and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct:âit continued and became more distinct: I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling; but it continued and gained definitivenessâuntil, at length, I found that the noise was

not

within my ears.

No doubt I now grew

very

pale;âbut I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increasedâand what could I do? It was

a low, dull, quick soundâmuch such a sound as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton

. I gasped for breathâand yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quicklyâmore vehemently; but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations, but the noise steadily increased. Why

would

they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observation of the menâbut the noise steadily increased. Oh God! what

could

I do? I foamedâI ravedâI swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louderâlouderâ

louder!

And still the men chatted pleasantly, and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God!âno, no! They heard!âthey suspected!âthey

knew!

âthey were making a mockery of my horror!âthis I thought, and this I think. But any thing was better than this agony! Any thing was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die!âand nowâagain!âhark! louder! louder! louder!

louder!â

“Villains!” I shrieked, “dissemble no more! I admit the deed!âtear up the planks!âhere, here!âit is the beating of his hideous heart!”

Son cÅur est un luth suspendu;

Sitôt qu'on le touche il résonne

.

âD

E

B

ÃRANGER

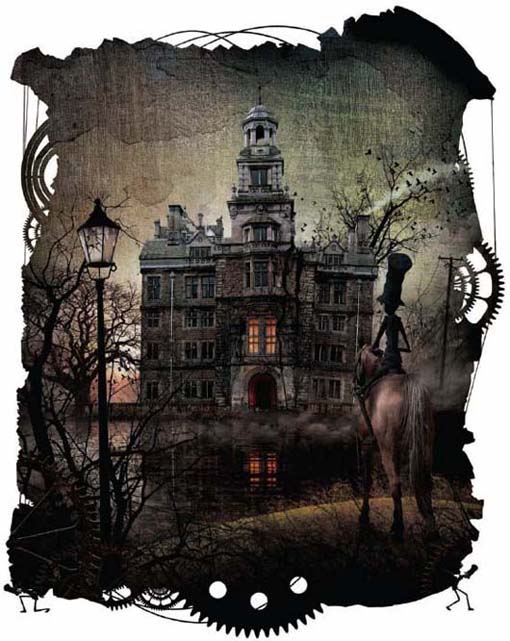

D

URING the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country, and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher. I know not how it wasâbut, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. I looked upon the scene before meâupon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domainâupon the bleak wallsâupon the vacant eye-like windowsâupon a few rank sedgesâand upon a few white trunks of decayed treesâwith an utter depression of soul which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveller upon opiumâthe bitter lapse into every-day lifeâthe hideous dropping off of the veil. There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heartâan unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime. What was itâI paused to thinkâwhat was it that so unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher? It was a mystery all insoluble; nor could I grapple with the shadowy fancies that crowded upon me as I pondered. I was forced to fall back upon the unsatisfactory conclusion, that while, beyond doubt, there

are

combinations of very simple natural objects which have the power of thus affecting us, still the analysis of this power lies among considerations beyond our depth. It was possible, I reflected, that a mere different arrangement of the particulars of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps to annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression; and, acting upon this idea, I reined my horse to the precipitous brink of a black and lurid tarn that lay in unruffled lustre by the dwelling, and gazed downâbut with a shudder even more thrilling than beforeâupon the remodelled and inverted images of the gray sedge, and the ghastly tree-stems, and the vacant and eye-like windows.

Nevertheless, in this mansion of gloom I now proposed to myself a sojourn of some weeks. Its proprietor, Roderick Usher, had been one of my boon companions in boyhood; but many years had elapsed since our last meeting. A letter, however, had lately reached me in a distant part of the countryâa letter from himâwhich, in its wildly importunate nature, had admitted of no other than a personal reply. The MS. gave evidence of nervous agitation. The writer spoke of acute bodily illnessâof a mental disorder which oppressed himâand of an earnest desire to see me, as his best and indeed his only personal friend, with a view of attempting, by the cheerfulness of my society, some alleviation of his malady. It was the manner in which all this, and much more, was saidâit was the apparent

heart

that went with his requestâwhich allowed me no room for hesitation; and I accordingly obeyed forthwith what I still considered a very singular summons.

Although, as boys, we had been even intimate associates, yet I really knew little of my friend. His reserve had been always excessive and habitual. I was aware, however, that his very ancient family had been noted, time out of mind, for a peculiar sensibility of temperament, displaying itself, through long ages, in many works of exalted art, and manifested, of late, in repeated deeds of munificent yet unobtrusive charity, as well as in a passionate devotion to the intricacies, perhaps even more than to the orthodox and easily recognizable beauties, of musical science. I had learned, too, the very remarkable fact, that the stem of the Usher race, all time-honored as it was, had put forth, at no period, any enduring branch; in other words, that the entire family lay in the direct line of descent, and had always, with very trifling and very temporary variation, so lain. It was this deficiency, I considered, while running over in thought the perfect keeping of the character of the premises with the accredited character of the people, and while speculating upon the possible influence which the one, in the long lapse of centuries, might have exercised upon the otherâit was this deficiency, perhaps, of collateral issue, and the consequent undeviating transmission, from sire to son, of the patrimony with the name, which had, at length, so identified the two as to merge the original title of the estate in the quaint and equivocal appellation of the “House of Usher”âan appellation which seemed to include, in the minds of the peasantry who used it, both the family and the family mansion.

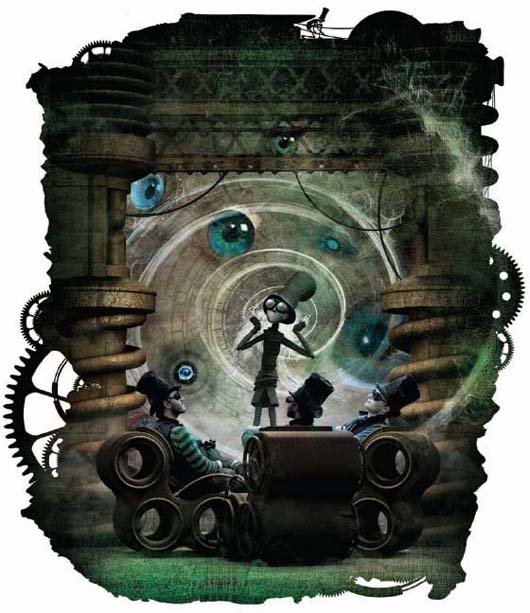

I have said that the sole effect of my somewhat childish experimentâthat of looking down within the tarnâhad been to deepen the first singular impression. There can be no doubt that the consciousness of the rapid increase of my superstitionâfor why should I not so term it?âserved mainly to accelerate the increase itself. Such, I have long known, is the paradoxical law of all sentiments having terror as a basis. And it might have been for this reason only, that, when I again uplifted my eyes to the house itself, from its image in the pool, there grew in my mind a strange fancyâa fancy so ridiculous, indeed, that I but mention it to show the vivid force of the sensations which oppressed me. I had so worked upon my imagination as really to believe that about the whole mansion and domain there hung an atmosphere peculiar to themselves and their immediate vicinityâan atmosphere which had no affinity with the air of heaven, but which had reeked up from the decayed trees, and the gray wall, and the silent tarnâa pestilent and mystic vapor, dull, sluggish, faintly discernible, and leaden-hued.

Shaking off from my spirit what

must

have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building. Its principal feature seemed to be that of an excessive antiquity. The discoloration of ages had been great. Minute fungi overspread the whole exterior, hanging in a fine tangled web-work from the eaves. Yet all this was apart from any extraordinary dilapidation. No portion of the masonry had fallen; and there appeared to be a wild inconsistency between its still perfect adaptation of parts, and the crumbling condition of the individual stones. In this there was much that reminded me of the specious totality of old wood-work which has rotted for long years in some neglected vault, with no disturbance from the breath of the external air. Beyond this indication of extensive decay, however, the fabric gave little token of instability. Perhaps the eye of a scrutinizing observer might have discovered a barely perceptible fissure, which, extending from the roof of the building in front, made its way down the wall in a zigzag direction, until it became lost in the sullen waters of the tarn.