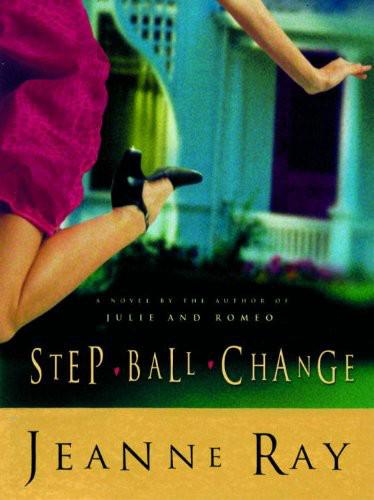

Step-Ball-Change

Also by

Jeanne Ray

J

ULIE AND

R

OMEO

Copyright © 2002 by Rosedog, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Shaye Areheart Books, New York, New York.

Member of the Crown Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc.

SHAYE AREHEART BOOKS is a registered trademark and the

Shaye Areheart Books colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ray, Jeanne.

Step-ball-change : a novel / by Jeanne Ray—1st ed.

1. Married people—Fiction. 2. Triangles (Interpersonal relations)—Fiction.

3. Raleigh (N.C.)—Fiction. 4. Atlanta (Ga.)—Fiction.

5. Rich people—Fiction. 6. Divorce—Fiction.

PS3568.A915 S74 2002

813′.6—dc21 2001053749

eISBN: 978-0-307-81634-4

v3.1

For my mother Eva Wilkinson

Thanks, Mom

Contents

Happiness in marriage is entirely a matter of chance

.

— J

ANE

A

USTEN

,

Pride and Prejudice

When your parachute strap is beginning to snap,

smile a big smile and tap, tap, tap your troubles away

.

— J

ERRY

H

ERMAN

,

Mack and Mabel

chapter one

I

T ALL STARTED ON

T

UESDAY NIGHT

. T

OM AND

I

WERE

having dinner when the phone rang.

Let me stop here for a minute. I want to revel in that sentence.

Tom and I were having dinner

. It almost sounds like this was something that happened regularly. In fact, my husband, who is a public defender, had made a career of eating peanut-butter-cheese crackers from the vending machine in the Raleigh courthouse while he went over the testimony of guys named Spit one more time. I had been teaching adult tap classes in the evenings to young women who didn’t have a date after work and were trying to improve themselves. That was not to say I was never home or Tom was never home, but it was hard to make it home simultaneously, and it was nearly impossible to be home alone. Our two oldest sons, Henry and Charlie, were married and gone, but George, our youngest, was still down the hall while he went to law school. Kay, our daughter, found her way over most nights to review cases with her father. And if none of the children were here, you could count on the fact that Woodrow, our contractor, and a couple of the plaster guys who worked for him would be sitting on the back porch having some fast food in the evening. Originally, Woodrow had come to build a glassed-in porch on the house, what we called a Florida room, but

halfway through the project he discovered that our foundation had shifted, and suddenly the cracks that were deep below the ground were spreading across our walls like ambitious ivy. The Florida room was abandoned in favor of the more pressing problems, and now stood as a naked frame of skinny poles on the side of our house. We had been under construction for six weeks, and I had come to think of the workmen as distant relatives who wanted to leave but had no place else to go.

But tonight the house was dark. When Tom and I called out no one answered back. Woodrow was gone and George was gone and the drop cloths were neatly folded and stacked. To further raise the odds on the rarity of this evening, I had actually bought the ingredients to make a pasta dish with olives and real tuna that I had seen in a magazine. So when I say, “Tom and I were having dinner,” I mean it was hot food, and we were alone together. Tom had been so hopeful as to put on a Stan Getz record, and “Girl from Ipanema” laced the air. The whole evening was a kind of far-fetched coincidence. There was potential-for-romance written all over it.

But there was a second half to that sentence:

The phone rang

.

Tom answered it and for a while after hello, he said nothing. He just listened with a puzzled expression that could mean he’d been snagged either by someone who wanted to steam-clean our carpets or by a very distant cousin whose kid was in jail. Public defenders were modern-day priests in a sense: If someone had done something wrong, they were quick to call Tom and confess. Then he started to say, “Kay? Kay?” and then listened again. He said, “Honey, are you all right? Take a breath. Try to take a breath. Are you all right?”

Words to make any mother put down her fork and jump to her feet. I gestured for him to give me the phone.

“Kay?” Tom said. “Do you think you could talk to your mother? I’m going to put your mother on the phone.” Tom’s voice sounded frightened. He had a better sense of the terrible things that can happen in the world than most people do. “She’s crying,” he said, holding his hand over the mouthpiece. “I can’t tell what she’s saying.”

“Kay?” I said. “Kay-bird?”

From the other end of the line there was a great deal of sobbing and snuffling, and immediately I felt my shoulders drop with relaxation. It was a sobbing and snuffling I knew. I can’t explain how. It was as if I came equipped with the secret decoder ring that made me capable of distinguishing the intent of my daughter’s cries. Even when she was a baby, I could tell from the other side of the house when she was hungry and when she needed changing and when she just wanted to be picked up and brought along for the ride. I could separate the cries of our three sons, too, but the difference was they stopped crying when they hit a certain age and Kay remained weepy by nature. Even now that she was thirty and a lawyer herself, she would find herself tearing up over an article in the newspaper or a commercial for long-distance service and have to excuse herself for a moment to go into another room and pull it together.

This crying, the subtle combination of gasping and a low, mucousy rattle that meant she wasn’t even taking the time to blow her nose, I knew to be a cry over love. I mouthed the word to Tom, “Dumped.” He raised his eyebrows and gave a sage shrug. Although it was a shame to think that such a thing had happened, neither of us was exactly surprised. Portraits of both Trey Bennett’s great-grandfather and his great-great-grandfather hung in what they called the library of the country club. I had seen them over the

years at wedding receptions and other inescapable social obligations. All the firstborn Bennett sons were named Conrad, though the grandfather was called Sergeant and the father was called, even on the most formal of occasions, Sport, and Trey was called Trey, indicating, one would think, that he was the third when in fact he must have been the sixth or seventh. The Bennett family was exhausting and inescapable in Raleigh, huge and recklessly blessed. They all had perfect teeth and Mercedes SUVs. They flew their own planes to their own summer houses and ski chalets. Their name was chipped into the marble of every hospital, art museum, and social register in the tri-city area. From what I could track in the paper over the years, they tended to marry young and reproduce enthusiastically, so Trey Bennett was a bit of an anomaly, being single at thirty-five. He was considered by everyone, especially his mother, to be the very definition of eligible. What he had been doing dating a thirty-year-old public defender who didn’t even know any debutantes, much less been one herself, was a mystery to all of us, and now poor Kay was sobbing, her heart having been skidded across the pavement at top speed yet again.

“Baby,” I said. “Deep breath. Come on now, try to relax.”

Tom sat back down at the table and started to eat the dinner that was already halfway to cold.

“I-baaa,” Kay said. “I-baaa.”

“It’s okay,” I said. I pointed at my plate and Tom slid it over to me. The pasta was getting stiff, but I managed to force a few pieces into a twirl around my fork.

I settled in and listened to Kay cry. Sometimes that’s all a mother can do. Truth be told, Trey had made me a little uncomfortable. Not that he wasn’t nice. He was extraordinarily nice. His manners would have made Cary Grant feel inadequate. But whenever

they stopped by our house, I was always aware that a family dog long since dead had peed on our only Oriental rug and left an irregular stain. When Trey was in the house, I wished I hadn’t come straight from the dance studio in my leotard and warm-ups. I wished I’d showered. The few times he came to dinner, he complimented everything lavishly, but I was always plagued by images of matching serving utensils and Venetian water glasses. After the third time, Tom and I decided it would be less stressful to take them out.