Still Foolin' 'Em (33 page)

Authors: Billy Crystal

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

But I’m still thinking double. The ump is thinking, Foul ball. I had made contact with a major league fastball. Okay, 1 and 1. Ball inside, 2 and 1, and another ball and it’s 3 and 1. I’m this close to getting to first base, just like at my prom. I look over, and Derek Jeter is in the on-deck circle yelling, “Swing, swing!”

The windup, the pitch. It’s a cutter. The nastiest cutter I’ve seen since my bris. But I swing and miss. The first time I’ve swung and missed in two days at Tampa. Now it’s 3 and 2. The crowd stands up. This is my only shot, my only at bat. Ever. Maholm winds, I look to the release point, and there it is: eighty-nine miles per hour, a cut fastball, the same pitch he threw to that obstructer of justice Barry Bonds. I swing over it. Strike three. I’m out of there.

I head back to the bench, but before I do, I check with the ump: “Strike?” He shakes his head no: low and inside. I’m so mad I missed it, and also mad I didn’t take the pitch, that I almost don’t hear the crowd standing and cheering. The guys are giving me high fives. Girardi hugs me, then Kevin Long, the great hitting coach, and then Jorge. Then, for the first time in baseball history, they stop the game and give the batter a ball for striking out. A-Rod hands it to me, saying, “Great at bat!” My teammates greet me as if I’ve just hit a home run. Mariano Rivera hugs me, and others keep saying the same thing:

“Six pitches, man, you saw six pitches!”

I sit with Yogi Berra and Ron Guidry for a few innings, and if that isn’t cool enough, I’m asked to come up to Mr. Steinbrenner’s office. In full uniform I walk into the boss’s lair. He gives me a big hug and then says with a straight face that I’ve been traded for Jerry Seinfeld. I thank him over and over again for a chance to be a Yankee, and he says he loved it and, most importantly, the fans loved it. That’s what it’s really all about.

* * *

Once the game is over and I’ve done my press, the clubhouse attendants hand me my uniform as a gift. Before I leave, I ask who was pulling those locker room pranks on me before the game.

“LaTroy Hawkins,” I’m told.

“What can I do to get back at him?”

“You want me to shit in his shoes?” someone asks.

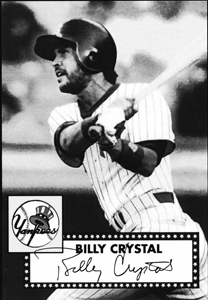

“No, but thanks—maybe something more clever,” I suggest. One of the attendants then says he has an idea. LaTroy has just gotten a pair of new dress shoes, so let’s screw them to the wall of his locker. How he thinks of that so quickly, I have no idea. He returns with a drill, and we take LaTroy’s brand-new $700 shoes and screw them to the back wall of his locker. Janice made fun baseball cards of me as a present, and I put one in each shoe, with a note saying, “Don’t fuck with my stuff.” I leave wishing I were coming back the next day.

I’ve had some great moments in my career, but nothing compares to the fact that I can say, “I was the leadoff man for the New York Yankees.” I realize, of course, that this was a once-in-a-lifetime event. But I say to all of you, as my mom said to me: Do something special on your birthday. Whatever you do, celebrate the fact that you’re here, and that people love you and you love them. We only do this once.

Let Him Go

My first memory is of being in a cemetery. I guess I was three years old, not aware of where I was, because I was playing leapfrog on various headstones as my family and the rest of the mourners were saying the Jewish prayer for the dead for my aunt Rose. Rose was a tiny wrinkled Russian woman with one arm several inches longer than the other. My dad claimed it was because she played trombone. She was so Russian-looking that you had the feeling you could twist her head off and another, smaller version of her would be inside. Anyway, I was just jumping away, carefree, on the flat chiseled granite markers when my father gently grabbed me by the back of the neck and said, “Don’t do that.” Thus began my relationship with my dad and death.

Growing up, I was always around the old, the sick, and the complaining. My relatives were very matter-of-fact about death: That’s it, and that’s all. “When I go, you can have my sweaters for half price.” Although my relatives were a joyous group, a low-hanging fog always seemed to surround them, and one by one they disappeared into it. My father led the parade by dying suddenly when I was just fifteen years old.

I missed him terribly for most of my life, always regretting never having had the chance to be face-to-face again, so I could say I was sorry about our last heated encounter. When I became a father and then a grandfather, there was always an empty pocket in my soul. Every time I’ve had a personal moment of joy—like my wedding, or the births of my daughters, their weddings, the births of my four grandchildren, or successes in my career—I’ve wished I could have shared it with him. This search for my father always becomes tangled with the vines of my own aging. We never had a chance to grow older together.

After my father’s death, his brother Berns, my uncle, took on an important role in my life. He always knew how to talk to me. Maybe it was the artist in him that understood that my jokes were my sketches, and my monologues were my paintings. He knew how to praise and how to form a criticism (which is more difficult). As time went on, life started to catch up to him—or, more accurately, death started to. It became clear that this giant was getting shorter every day. Normal functions were being robbed from him, yet he never complained, except to say, “The golden years are brass.”

After he collapsed at Jenny’s wedding brunch, he made me his medical proxy, which meant that at some point in his inevitable demise I would be the one to say, “No more, that’s enough.” Somehow, I never thought that day would come. But in August 2008, I got an urgent phone call from his doctor in New York, who told me that Berns had had what appeared to be a stroke, and death was imminent.

“What do you want to do if we get into that area where a decision is needed whether to resuscitate him or not?” he asked me.

I suddenly felt angry at my uncle. I knew he’d given me this power because he loved and trusted me, but I really didn’t want it. “It’s tough playing God,” his doctor said.

“It’s tougher playing nephew,” I responded weakly.

Berns was in a semicomatose state for weeks, a humbling and insulting journey for this vibrant warrior. I felt a strong urge to say to him, “Uncle, maybe it’s time to stop fighting,” but then I would get scared and mad at myself. Some days, there were flickers of hope, which I clung to, the way a little child hangs on to the first dime he is given. You squeeze it as hard as you can, so no one can take it away. But I was now sixty years old, so far from the carefree child in a cemetery jumping on headstones—stones that now bore the names of all my uncles and aunts, grandparents, my dad, and now my mother, as well.

Growing older with Berns was one of the great gifts in my life. I wasn’t ready to say, “No more, that’s enough.”

One night, alone and exhausted by the consuming worry about Berns, I fell asleep early. Janice was visiting her parents, who were nervously preparing for a most delicate surgery on my father-in-law. It seemed that impending doom was everywhere. I awoke startled, in the dark, feeling scared and suddenly very cold, which was strange, because it was August and I don’t use the air-conditioning. I felt someone next to me, standing alongside the bed. I was frozen with fear, and as cold as I was, I was also sweating profusely. I turned slowly and fearfully, thinking it was some sort of home invader. In the dark, I saw a shadowy figure that appeared to be wearing a long black coat, with a cowl covering its head. I didn’t have the courage to look at its face, though I could sense that it had one. It didn’t speak, but I felt a message being transmitted into my head: “Let him go.… It’s time.” These words were repeated several times before I sensed that the presence had left. The room was warm again. I looked at the clock; it was three-ten in the morning.

My heart was beating through my soaked T-shirt. I flipped on the light and walked around the house, splashed some water on my face, toweled off. I gazed out the window at the night and its stars, and I knew what had happened. My father had come to me, to tell me it was okay to let Berns go. I had seen those shows where people swear they’ve been visited from the “other side,” and I’d never believed them. Now I did.

Performing

700 Sundays

had given me some sense of peace and closure. The last scene in the show has me meeting my father in heaven, and he forgives me. After each performance, I would feel so enriched, so grateful for the chance to act this out. But that was a play; this was so real. It sounds crazy, but I really believed he had come. I stayed up until Janice returned the next day.

“It was the air conditioner,” she said, looking at me as if I had three heads.

“No, I didn’t have it on.” I felt like Richard Dreyfuss in

Close Encounters.

I also told a few friends what had happened. Some nodded and listened patiently; others, I got the feeling, thought I had imagined it or simply made it up, considering the circumstances. I must have sounded like those people in the trailer park who swear that a spaceship landed and a little green man emerged and asked them for change for a twenty. But I never questioned the experience.

Unnerved by the encounter, to say the least, I received a call just as I landed in New York. I was there to attend the final game at old Yankee Stadium. ESPN had requested that I commentate for an inning during this final broadcast. Since Dad had introduced me to it in 1956, the park had become a sanctuary for me. If ballparks can be called cathedrals, then this was my synagogue. The phone call was from the doctor, who told me Berns might not last the night. One of those evil “hospital infections” had found an easy target. I entered his hospital room with terrible fear.

I wasn’t there when either of my parents died, and I’d been angry at them for not waiting for me. But God doesn’t have to wait for anyone, does he? I held Berns’s hand and whispered the punch line of a dirty joke he had told me when I was a kid; it was our way of saying hello. “An eagle swallows a mouse whole and is flying up to the clouds when the mouse crawls out of the eagle’s asshole and says, ‘Eagle, how high are we?’ The eagle says, ‘Five thousand feet.’ A few minutes later, the mouse again asks, ‘Eagle, how high are we?’ ‘Ten thousand feet,’ says the eagle. One last time the mouse pops his head out and asks, ‘Eagle, how high are we?’ The eagle says, ‘Twenty thousand feet,’ and the mouse says, ‘You ain’t shitting me, are you?’” So that’s what I whispered in his ear: “You ain’t shitting me, are you?”

He moved his head slightly, sensing where I was, and a huge diamond of a tear rolled down his exhausted face and onto his gown, the stain spreading. “Don’t cry, Uncle, you’re going to get better,” I said. I think he wasn’t crying for himself; he was crying for me. I left hours later, sure I wouldn’t see him again.

I slept in my clothes, alongside the phone. It rang at nine the next morning. “Come, Billy,” his aide told me. “The fever broke and he’s very alert.”

I raced over. “You ain’t shitting me, are you?” He opened both eyes, something he hadn’t been able to do for weeks, and smiled. I held his hand, and he immediately started to fail. The nurse rushed in and told me to keep talking to him, for he was passing away. I was still holding his hand, and if God was going to take him, it would be one hell of a tug-of-war. I began panicking. The nurse calmed me down and told me to talk him through it.

“It’s okay to go.… I love you,” I said.

“He waited for you,” the nurse whispered, listening to his failing heart.

Miraculously, Berns held on, and the episode ended. I was terrified and exhausted. It was like being on a raft in the ocean and a shark takes a bite out of it and swims off, but it’s only a matter of time before he returns for more. My brother Joel arrived, and we sat by the foot of our beloved uncle’s bed. Berns was alert, though his agonal breathing sounded ominous, and we could hear the dreaded rattle. He did manage to get a huge laugh out of everyone when a young resident asked him how he was feeling. Uncle Berns never said a word; he opened both eyes—again, something he hadn’t done for a month—and, in a perfect Oliver Hardy moment, stared at the resident as if to say, “You are a moron.”

His daughter, Dorothy, arrived, and my daughter Lindsay and her fiancé, Howie, as well. Berns labored again, and then it happened so quickly. The doctor told us once again that he was failing. We gathered around Berns, I held his right hand, and we all told him good-bye and encouraged him to go. He loved to sing “I Got Shoes,” an old spiritual that ends with “When I get to heaven, gonna put on my shoes, and walk all over God’s heaven.” I saw him trying so hard to stay alive, but his body was making the transition, and I found myself saying into his ear, “Put on your shoes.”

He made a slight motion of his head to me, there was a hint of resignation, a glimmer of a smile, and he stopped breathing. He was gone.

No one had ever died in front of me. It’s not pleasant, but it was what I’d always wanted in my thoughts of my parents’ deaths. They were there when I came into this world; I should have been there when they left it. I had been through the experience now with the last link to my father. It was fitting, I thought, that on the day Yankee Stadium expired, my uncle, the brother of my father, who taught me to love that place, would also expire. Also, as was revealed that night, the new stadium would open on April 16, my father’s one hundredth birthday. The next day, I had one last good-bye at the funeral home before Berns was sent on his way to be cremated, per his wishes. He hadn’t wanted a funeral—to be laid out, as he said, looking “like the last pastry on the cart.”