Still Foolin' 'Em (5 page)

Authors: Billy Crystal

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

During my last season of high school baseball, I was the captain of the team, hit .346, and even belted my first home run. Against a Calhoun High School pitcher who was later drafted by the Houston Astros, I took a high inside fastball and turned on it. It sailed over the fence at the 325-foot sign in left center field. As I approached first base and saw it clear the wall, I yelled, “Oh, baby!” When I rounded third, my coach, Gene Farry, was waiting for me. He shook my hand and whispered, “Don’t say that again.” He was right, but I was just so damned happy.

As Little Orphan Annie—Long Beach High

Swing Show

.

That May, my buddy Neil Chusid introduced me to a young man named Lew Alcindor. Neil and Lew were classmates at Power Memorial Academy, in Manhattan. At over seven feet tall, Lew was the number one high school basketball player in the country and was on his way to UCLA; changing his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, he became one of the NBA’s all-time greats. We got to be friends, and Lew came over quite a lot and loved our family’s connections to the world of jazz and its African American musicians.

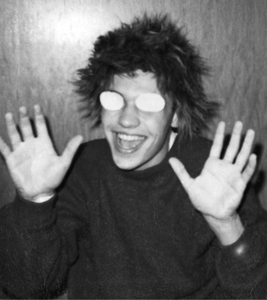

One beautiful spring day, Lew, Neil, and I decided to play some hoops at the local basketball courts in Long Beach. We walked on the boardwalk toward the center of town. Lew was wearing a UCLA T-shirt, a panama hat, and round red John Lennon sunglasses. He looked at me and said, “You’re not cool enough—wear these.” He gave me his red sunglasses and Neil the hat. We arrived at the famous courts at Central School. Larry Brown, now a Hall of Fame basketball coach, had made these courts his home when he’d attended Long Beach High. College and high school players from all over came to Central School on Saturdays to play against one another. The games were in full swing as the three of us sauntered onto the courts: five-foot-eight Neil in his wide-brimmed hat, trying to look “bad”; five-foot-seven me with my red glasses, trying to walk like I was six-five; and the most famous seven-foot-two high school athlete in America. The players just stared at us as I uttered, “We have next.” We didn’t lose a game until we got hungry and Lew said, “That’s enough—thanks, guys.” Neil put on his hat, I put on my red sunglasses, and we walked out the way we had come in.

In June I was handed my diploma. After an anxious summer saying good-bye to my friends and family and all I had ever known, I got on a plane and headed to Marshall University, in Huntington, West Virginia.

Sitting alone on the plane as it flew south was a strange feeling. Not unlike how I feel at sixty-five. How did this happen so soon? I had never been away to camp, had rarely even slept over at a friend’s house, and now I was on my way to my first year of college. After a harrowing landing at the Huntington airport (the runway was just over the lip of a mountain), I arrived at the Hotel Prichard, which would be my dormitory. The school had taken two floors of the hotel because of a lack of dorm space. My roommate wasn’t in yet and our bunk beds weren’t even assembled, so that first night I slept on a mattress on the floor. After my collect call home to say I had made it, words I barely got out because of the lump in my throat, I walked into town to look around and get a bite to eat at the White Pantry, a nearby burger joint. I was wearing a T-shirt, and my Star of David necklace peeked over it. I ordered a cheeseburger, and the counterman said they were closed, which they weren’t; the place was packed. He pointed to the sign on the wall that said,

WE RESERVE THE RIGHT TO REFUSE SERVICE TO ANYONE.

He then motioned to my Star of David, and I stood up and walked out.

* * *

I got a job as a DJ on WMUL, the campus radio station, and had two shows: one of my own, called

Just Jazz,

and another called

Nightlife,

which I did with a partner named Tom Tanner. We’d be on late at night in Huntington, and after a while people started listening. It was a way for me to perform and be funny, and it was just like I was home doing bits on our tape recorder with my brothers.

High school graduation, June 1965. I think this was taken by Lew Alcindor.

I was hoping to be the second baseman for the Thundering Herd, but the school had canceled the freshman baseball program, so that dream would have to wait until my sophomore year. I was very shy, didn’t really date anybody, and even taught a Sunday school theater class at the local synagogue. My roommate, Mike Hughes, was a great guy; we were a solid pair even though he was in his mid-twenties and I was only seventeen. We made up some phony proof of age so I could get a beer now and then. One day, I was talking to some of the guys in the dorm about Lew Alcindor, and they doubted that I knew him. I bet a bunch of them five bucks each. So I wrote a letter to Lew care of UCLA, and in a short time I got a letter back, which earned me a lot of dorm cred and seventy-five dollars.

“You are listening to

Just Jazz

here on WMUL—the voice of Marshall University. I’m Billy Crystal.”

Then I told Mike that I could sneeze at will. I have a chemical reaction to dark chocolate that can cause me to sneeze uncontrollably. Up until then, my record was fifty sneezes before my nose bled. Mike thought this could be great fun. So he got a group of guys together in the rec room and they all threw five bucks into a hat, and I ate a large bar of dark chocolate. I sat in the middle of the jammed room with everybody starring at me. Within five minutes, someone in the crowd said, “Hey, his ears are getting red,” which to me meant “Gentleman, start your engines.” The bet was fifty sneezes or better.

Achoo!

came the first. “One,” said Mike, who was holding the pot.

Achoo!

“Two,” said Mike. As the count grew, so did the amount of people in the room, all calling out the number as I sneezed away. I passed thirty-five easily, and guys threw more money into the hat. Forty-eight, forty-nine, fifty sneezes! Still not done but exhausted, somehow I worked my way up to sixty-four before a trickle of blood hit my upper lip. I made $225 and a few new friends.

I came home that summer and went to work as a counselor for my old teacher Chuck Polin at a day camp he ran at the Malibu Beach Club. One day while I was playing catch on the beach with a friend, this girl walked by. I followed her, and we started talking and then dating. I was in love, and I knew that if I went back to Marshall we’d never make it. Long-distance relationships rarely work out. I didn’t want to let that happen. I transferred to Nassau Community College, only twenty minutes from Long Beach.

It’s the best decision I ever made.

Count to Ten

As we face the challenges of getting older, some people want the comfort of knowing that there is a God watching out for them. People say it is a given that as you get older, you turn to religion. Personally, the aging friends I know have turned to the Holy Trinity: Advil, bourbon, and Prozac. Finding a relationship with God (if you believe in one) is littered with speed bumps. Now, I’d love to believe that there is a God watching out for us, but I can’t. How would he explain things? “God, why did you take my father when I was fifteen?” “Did I? Oh, yeah, I was getting a root canal that day … my bad.”

“What about Vietnam? World War II, Hiroshima, the tsunami in the Philippines?”

“Uh, migraine, I had a migraine. Plus, Vietnam’s not my fault—even I can’t control the CIA.”

“Hurricane Sandy?”

“It was supposed to miss the East Coast by two hundred miles. I left the word ‘miss’ out of my e-mail to Mother Nature.”

Can we have all these awful moments in our lives and believe that God had a hand in them? Think about it: when some ballplayers hit a home run and step on home plate, they immediately point to the sky, yet when they make an error or strike out, they don’t point anywhere. Didn’t the same God watch over them? Most people who are religious can be divided into four groups: the fanatics (the ones who want to kill everyone who is not them); the true believers (those who accept on faith that what science and common sense tell them is a bit far-fetched; I can’t specify who fits this category, but let’s just say that I’m not quite ready to go with the idea that seventy-five million years ago Xenu brought billions of his people to Earth, stacked them around volcanoes, and killed them using nuclear weapons); the spiritual (those who use their Good Book and teachings as a way to connect with something deeper than themselves); and the cultural (those who identify less with God and more with which deli has the best corned beef).

But as we age and feel that our time is dwindling, we need something because we’re terrified. Terrified that this is it. Hoping that this God who has screwed up over and over will come to us and make it all better. We’re Charlie Brown and we want to believe, we need to believe, that this one time Lucy won’t yank the football away. The problem is that just as we want to become closer to God and have something to put our faith in, our life experiences have taught us to be disillusioned with organized religion. Especially if you are a former altar boy.

All religions have disillusioned followers. My personal disillusionment began at my “Count to ten” moment at my Bar Mitzvah. To add insult to injury, they kept telling me this was the day I would become a man, and that didn’t happen until I was seventeen.

Don’t get me wrong—I think all the basic tenets of my religion are great: fairness, education, respect, kindness. But let’s face it: our holidays can’t help but add to the disillusionment, because they lag far behind. Take New Year’s celebrations.

My favorite photo: March 25, 1961, my Bar Mitzvah reception. Jazz great Henry “Red” Allen performed. He was a guest who got up and jammed. Not many Bar Mitzvahs turn into jam sessions.

With the Chinese New Year, there are dragons, parades, firecrackers. With New Year’s in America, there are big parties, the ball drops in Times Square, you get drunk, tell someone you love them, and throw up on their shoes. With the Jewish New Year, we fast, we can’t turn on the lights, we confess our sins. Happy New Year! What a party! A bunch of guilty, hungry people sitting in the dark.