Stochastic Man (15 page)

Authors: Robert; Silverberg

“Go ahead. Who’ll stop you?”

He lit up, and I joined him. His ebullience was disconcerting and almost frightening. At our other two meetings Carvajal had appeared to be drawing on reservoirs of strength long since overdrawn, but today he seemed speedy, frantic, full of a wild energy obtained from some hideous source: I speculated about mysterious drugs, transfusions of bull’s blood, illicit transplants of organs ripped from unwilling young victims.

He said suddenly, “Tell me, Lew, have you ever had moments of second sight?”

“I think so. Nothing as vivid as what you must experience, of course. But I think many of my hunches are based on flickers of real vision—subliminal flickers that come and go so fast I don’t acknowledge them.”

“Very likely.”

“And dreams,” I said. “Often in dreams I have premonitions and presentiments that turn out to be correct. As though the future is floating toward me, knocking at the gates of my slumbering consciousness.”

“The sleeping mind is much more receptive to things of that sort, yes.”

“But what I perceive in dreams comes to me in symbolic form, a metaphor rather than a movie. Just before Gilmartin was caught I dreamed he was being hauled before a firing squad, for example. As though the right information was reaching me, but not in literal one-to-one terms.”

“No,” Carvajal said. “The message came accurately and literally, but your mind scrambled and coded it, because you were asleep and unable to operate your receptors properly. Only the waking rational mind can process and integrate such messages reliably. But most people who are awake reject the messages altogether, and when they are asleep their minds do mischief to what comes in.”

“You think many people get messages from the future?”

“I think everyone does,” Carvajal said vehemently. “The future isn’t the inaccessible, intangible realm it’s thought to be. But so few admit its existence except as an abstract concept. So few let its messages reach them!” A weird intensity had come into his expression. He lowered his voice and said, “The future isn’t a verbal construct. It’s a place with an existence of its own. Right now, as we sit here, we are also

there, there plus one, there plus two, there plus n

—an infinity of

theres,

all of them at once, both previous to and later than our current position along our time line. Those other positions are neither more nor less ‘real’ than this one. They’re merely in a place that happens not to be the place where the seat of our perceptions is currently located.”

“But occasionally our perceptions—”

“Cross over,” Carvajal said. “Wander into other segments of the time line. Pick up events or moods or scraps of conversation that don’t belong to ‘now.’“

“Do our perceptions wander,” I asked, “or is it the events themselves that are insecurely anchored in their own ‘now’?”

He shrugged. “Does that matter? There’s no way of knowing.”

You don’t care how it works? Your whole life has been shaped by this and you simply don’t—”

“I told you,” Carvajal said, “that I have many theories. So many, indeed, that they tend to cancel one another out. Lew, Lew, do you think

I don’t care? I’ve spent all my life toying to understand my gift, my power, and I can answer any of your questions with a dozen answers, each as plausible as the next. The two-times-lines theory, for example. Have I told you about that?”

“No.”

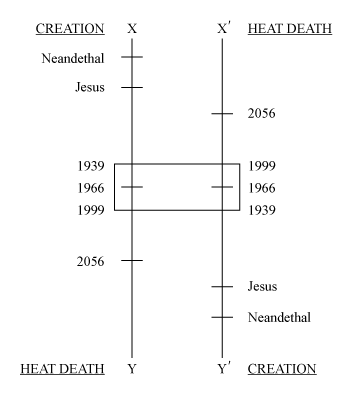

“Well, then.” Coolly he produced a pen and drew two firm lines parellel to each other across the tablecloth. He labeled the ends of one line X and Y, the other X' and Y'. “This line that runs from X to Y is the course of history as we know it. It begins with the creation of the universe at X and ends with thermodynamic equilibrium at Y, all right? And these are some significant dates along its path.” With fussy little strokes he sketched in crossbars, beginning at the side of the table closer to himself and proceeding toward me. “This is the era of Neanderthal man. This is the time of Jesus. This is 1939, the start of World War Two. Also the start of Martin Carvajal, by the way. When were you born? Around 1970?”

“1966.”

“1966. All right. This is you, 1966. And this is the present year, 1999. Let’s say you’re going to live to be ninety. This is the year of your death, then, 2056. So much for line X-Y. Now this other line, X'-Y'—that’s also the course of history in this universe, the very same course of history denoted by the other line.

Only it runs the other way.”

“What?”

“Why not? Suppose there are many universes, each independent of all the others, each containing its unique set of suns and planets on which events occur unique to that universe. An infinity of universes, Lew. Is there any logical reason why time has to flow in the same direction in all of them?”

“Entropy,” I mumbled. “The laws of thermodynamics. Time’s arrow. Cause and effect.”

“I won’t quarrel with any of those ideas. So far as I know they’re all valid within a closed system,” said Carvajal. “But one closed system has no entropic responsibilities relative to another closed system, does it? Time can tick from A to Z in one universe and from Z to A in another, but only an observer outside both universes is going to know that, so long as within each universe the daily flow runs from cause to effect and not the other way. Will you admit the logic of that?”

I shut my eyes a moment. “All right. We have an infinity of universes all separate from one another, and the direction of time-flow in any of them may seem topsyturvy relative to all the others. So?”

“In an infinity of anything, all possible cases exist, yes?”

“Yes. By definition.”

“Then you’ll also agree,” Carvajal said, “that out of that infinity of unconnected universes there may be one that’s identical to ours in all particulars, except only the direction of its flow of time relative to the flow of time here.”

“I’m not sure I grasp—”

“Look,” he said impatiently, pointing to the line that ran across the tablecloth from X' to Y'. “Here’s another universe, side by side with our own. Everything that happens in it is something that also happens in ours, down to the most minute detail. But in this one the creation is at Y’ instead of X and the heat death of the universe is at X' instead of Y. Down here”—he sketched a crossbar across the second line near my end of the table— “is the era of Neanderthal man. Here’s the Crucifixion. Here’s 1939, 1966, 1999, 2056. The same events, the same key dates, but running back to front. That is, they look back to front if you happen to live in this universe and can manage to get a peek into the other one. Over there, naturally, everything seems to be running in the right direction.” Carvajal extended the 1939 and 1999 crossbars on the X-Y line until they intersected the X- Y' line, and did the same for the 1999 and 1939 crossbars on the second line. Then he bracketed both sets of crossbars by connecting their ends, to form a pattern like this:

A waiter passing by glanced at what Carvajal was doing to the tablecloth and, coughing slightly, moved on, saying nothing, keeping his face rigid. Carvajal didn’t seem to notice. He continued, “Let’s suppose, now, that a person is bora in the X to Y universe who is able, God knows why, to see occasionally into the X'-Y' universe. Me. Here I am, going from 1939 to 1999 in X-Y, peeking across now and then into X'-Y' and observing the events of their years 1939 to 1999, which are the same as ours except that they’re flowing by in the reverse order, so at the time of my birth here everything in my entire X-Y lifetime has already happened in X'-Y’. When my consciousness connects with the consciousness of my other self over there, I catch him reminiscing about his past, which coincidentally is my future.”

“Very neat.”

“Yes. The ordinary person confined to a single universe can roam his memory at will, wandering around freely in his own past. But I have access to the memory of someone who’s living in the opposite direction, which allows me to ‘remember’ the future as well as the past. That is, if the two-time-lines theory is correct.”

“And is it?”

“How would I know?” Carvajal asked. “It’s only a plausible operational hypothesis to explain what happens when I

see.

But how could I confirm it?”

I said, after a time, “The things you

see

—do they come to you in reverse chronological order? The future unrolling in a continuous scroll, that sort of thing?”

“No. Never. No more than your memories form a single continuous scroll. I get fitful glimpses, fragments of scenes, sometimes extended passages that have an apparent duration of ten or fifteen minutes or more, but always a random jumble, never any linear sequence, never anything at all consecutive. I learned to find the larger pattern myself, to remember sequences and hook them together in a likely order. It was like learning to read Babylonian poetry by deciphering cuneiform inscriptions on broken, scrambled bricks. Gradually I worked out clues to guide me in my reconstructions of the future: this is how my face will look when I’m forty, when I’m fifty, when I’m sixty, these are clothes I wore from 1965 to 1973, this is the period when I had a mustache, when my hair was dark, oh, a whole host of little references and associations and footnotes, which eventually became so familiar to me that I could

see

any scene, even the most brief, and place it within a matter of weeks or even days. Not easy at first, but second nature by this time.”

“Are you

seeing

right now?”

“No,” he said. “It takes effort to induce the state. It’s rather like & trance.” A wintry look swept his face. “At its most powerful it’s a kind of double vision, one world overlying the other, so that I can’t be entirely sure which world I’m inhabiting and which is die world I

see.

Even after all these years I haven’t fully adjusted to that disorientation, that confusion.” He may have shuddered then. “Usually it’s not so intense. For which I’m grateful.”

“Could you show me what it’s like?”

“Here? Now?”

“If you would.”

He studied me a long moment. He moistened his lips, compressed them, frowned, considered. Then abruptly his expression changed, his eyes becoming glazed and fixed as though he were watching a motion picture from the last row of a huge theater, or perhaps as if he were entering deep meditation. His pupils dilated and the aperture, once widened, remained constant regardless of the fluctuations of light as people walked past our table. His face showed evidence of great strain. His breathing was slow, hoarse, and regular. He sat perfectly still; he seemed altogether absent. A minute, maybe, elapsed; for me it was unen- durably long. Then his fixity shattered like a falling icicle. He relaxed, shoulders slumping forward; color came to his cheeks in a quick pumping burst; his eyes watered and grew dull; he reached with a shaky hand for his water glass and gulped its contents. He said nothing. I dared not speak.

At length Carvajal said, “How long was I gone?”

“Only a few moments. It seemed a much longer time than it actually was.”

“It was half an hour for me. At least.”

“What did you

see?”

He shrugged. “Nothing I haven’t

seen

before. The same scenes recur, you know, five, ten, two dozen times. As they do in memory. But memory alters things. The scenes I

see

never change.”

“Do you want to talk about it?”

“It was nothing,” he said offhandedly. “Something that’s going to happen next spring. You were there. That’s not surprising, is it? We’re going to spend a lot of time together, you and I, in the months to come.”

“What was I doing?”

“Watching.”

“Watching what?”

“Watching me,” Carvajal said. He smiled, and it was a skeletal smile, a terrible bleak smile, a smile like all the smiles he had smiled that first day in Lombroso’s office. All the unexpected buoyancy of twenty minutes ago had gone out of him. I wished I hadn’t asked for the demonstration; I felt as though I’d talked a dying man into dancing a jig. But after a brief interval of embarrassing silence he appeared to recover. He took a swaggering pull at his cigar, he finished his sherry, he sat straight again. “That’s better,” he said. “It can be exhausting sometimes. Suppose we ask for the menu now, eh?”

“Are you really all right?”

“Perfectly.”

“I’m sorry I asked you to—”

“Don’t worry about it,” he said. “It wasn’t as bad as it must have looked to you.”