Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (32 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

A

AMELANCHOLY FATE

Lutine

was originally a 26-gun frigate of the French Royal Navy, launched in Toulon in 1779 as

La Lutine

. Some years later, during the French Revolution, she was one of a dozen ships delivered to Admiral Hood

by

loyalists to prevent their use by Bonaparte, and in 1793 the vessel was commissioned into the Royal Navy under the name of HMS

Lutine

.

She was mainly used for convoy escort work, piloting larger transports through the treacherous waters off the coast of Holland. In October 1799 she was tasked to carry over £1 million in gold bullion and coin from England to Germany. The bullion was intended to fund German banks threatened with a stock market crash, the coin to pay troops fighting in Holland.

Lutine

left English waters in the early morning of 9 October 1799 under the command of Captain Lancelot Skynner. Later that day she encountered a heavy northwesterly gale off the Dutch coast and struck on a sandbank. With a fierce tide coming in it was impossible for local boats to go to her aid, and by daybreak the next morning

Lutine

was smashed to pieces. Out of some 240 crew aboard, just one survived.

The loss of the ship was reported to the Admiralty by the commander of the local British squadron: ‘It is with extreme pain that I have to state to you the melancholy fate of HMS

Lutine

…’

The cargo was insured by Lloyd’s underwriters, who paid the claim in full, but ownership of the treasure that went down with the ship was disputed between the Dutch and the English. Several attempts over the years were made to retrieve some of the treasure, but much remains in Neptune’s Realm.

The ship’s bell, recovered in 1858, took on a unique role and has hung in four successive Lloyd’s Underwriting Rooms. For many years whenever a vessel became overdue underwriters involved in insuring the vessel would ask a specialist broker to reinsure some of their liability in the light of the possibility of the ship becoming a total loss. When reliable information about the vessel became available, the bell was rung once for bad news – such as total loss – or twice for a safe arrival or positive sighting. This ensured that all brokers and underwriters with an interest in the risk became aware of the news simultaneously

.

The ringing of the Lutine Bell is now restricted principally to ceremonial occasions.

HMS

HMSLutine.

S

O NEAR, YET SO FAR

Early on the morning of 23 November 1797 the Royal Navy frigate HMS

Tribune

made landfall in the approaches to the harbour at Halifax, Nova Scotia. She was part of a convoy escort for merchant vessels from England bound for Canada but had become separated from the other ships in heavy weather out in the Atlantic. Her captain proposed that they wait until a pilot could come aboard, but the master assured him that this was not necessary as he knew the harbour well.

Not long afterwards soldiers of the 7th Fusiliers stationed at York Redoubt watched with disbelief as

Tribune

careered on to Thrumcap Shoal less than 2 km from the harbour mouth. From their position on top of the high bluffs they relayed

Tribune

’s distress signals to the dockyard. Boats put out from the harbour to go to the assistance of the stranded vessel, but strong winds forced them back.

In an effort to lighten the ship, her starboard guns were manhandled over the side. That evening

Tribune

floated off the shoal but she had lost her rudder and there was 2 m of water in the hold. The pumps were worked furiously, and at first they seemed to be succeeding, but as the storm worsened the sea flooded in. The raging winds drove the ship inexorably towards the craggy shore on the other side of the harbour, then suddenly she lurched and sank in shallow water just off the entrance to Herring Cove.

Nearly 250 sailors found themselves struggling in the icy waves. Those

who

tried to swim to shore were smashed against the rocks. Eventually around 100 survivors managed to climb into the rigging, which protruded above the waves, but as night wore on many fell off through exhaustion and were swept away in the frigid waters.

All night people on shore at Herring Cove kept a grim vigil by the light of bonfires. They were so close to the wreck that they could hear the hopeless cries of the weakening survivors, but could no nothing.

The following morning a 13-year-old boy named Joe Cracker set out from the shore in a small skiff and with great courage and skill managed to bring it to the wreck and take off two men. His example inspired others, and shortly afterwards the rest were rescued, but just 12 out of 250 of the ship’s company had survived.

Edward, Duke of Kent, then resident in Halifax, personally thanked Cracker for his courage and asked him to name a reward. The boy requested a pair of warm corduroy breeches.

The location of the tragic sinking was named Tribune Head. A plaque at the headland at Herring Cove reads: ‘In memory of the heroism of Joe Cracker the fisher lad of 13 years who was the first to rescue survivors from the wreck of HMS

Tribune

.’

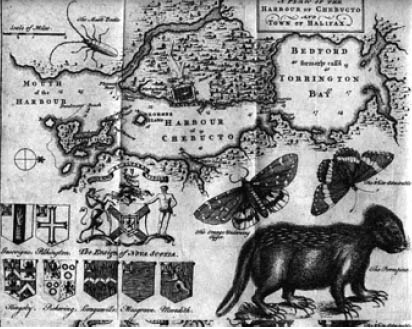

Eighteenth-century map of Chebucto Harbour and Halifax

Eighteenth-century map of Chebucto Harbour and Halifax.

T

HE FUNERAL THAT BURIED A FLEET

In 1566 in the Baltic Sea a fleet of the Swedish navy met a fleet of ships from Denmark and Lübeck in a battle during which a Danish commander was killed by a cannonball. A storm was brewing and, as was the custom, the opposing forces ceased fire and went their separate ways. The Swedish fleet disappeared into the Stockholm archipelago and the Danish-Lübeck forces formed a funeral procession and set course for the nearest Danish territory, the island of Gotland. The Lübeckians had wanted to go initially to Danzig, where their battle-scarred ships could be repaired, but the Danes insisted that the dead must be buried first.

Arriving off the Gotland port of Visby, Jens Truidson, the Danish Vice-Admiral commanding the fleet, was advised by harbour authorities not to anchor in the roadstead as it was a foul ground, and in anything other than a flat calm there was a great risk of anchors dragging. But the admiral, determined on honouring their dead, ignored the warning and ordered his 39 ships to anchor. They then began the gruesome business of ferrying the dead ashore.

The following day a burial service was held in Visby Cathedral, and the squadron prepared to leave the next morning. The weather was calm initially, but then the sky went a strange colour and the sea seemed to shimmer beneath the ships. That night Visby was hit by a terrible storm that lasted for six hours. Anchors were ripped from the seabed and cables snapped. The unwieldy ships of the Danish-Lübeck fleet collided with each other or were dashed to pieces on the jagged shoreline as they tried to sail away.

At daybreak the beach was covered with debris and dead bodies. More than one-third of the fleet was gone: 15 ships had sunk and the storm had claimed between 5,000 and 7,000 lives. (To put this into perspective, the population of Stockholm at the time was 9,000.) Among the dead were Admiral Truidson and his wife, two other admirals and the mayor of Lübeck; their remains were buried in Visby Cathedral. It was a hot summer and the people of Visby, fearing an epidemic could break out, hastily buried the rest of the dead in mass graves.

A Lübecker of 1540

A Lübecker of 1540.

BROUGHT UP SHORT – forced to a standstill by a sudden reversal of fortune.

DERIVATION

: a vessel under way was said to be brought up short if she was forced to shudder to an emergency stop by dropping her anchors, for example on unexpectedly sighting a coast looming through a thick fog.

A

ADOCKYARD’S NIGHTMARE

With so many combustibles around, fire was an ever-present danger in a dockyard. In 1774 Portsmouth dockyard, Britain’s biggest at that time, had already suffered two serious conflagrations in living memory.

In the late afternoon of 7 December fire broke out in the rope house. All but two of the workers had left the building by then, but once the alarm was raised hundreds of men quickly arrived on the scene, well aware that should a fire take hold there would be huge destruction. In addition to all the hemp, timbers, workshops and tools there were five ships in dry dock for repairs and a number of warships on slips in various stages of construction. Fortunately, although the rope house was destroyed, the fire was contained.

Initially the blaze was thought to have been an accident, but the evidence pointed to arson and a hunt began for the perpetrator. Suspicion fell on a man who was known as John the Painter, and an advertisement was placed in newspapers offering a reward for his apprehension.

Somewhat of a social misfit, John the Painter’s real name was James Hill, alias Hinde, alias Aitken. He had previously fled overseas to the American colonies to avoid arrest for a number of crimes. There he had consorted with political revolutionaries and come up with the wild plan of setting fire to England’s dockyards.

On 10 March 1775 a shackled Hill was transported to the dockyard, the scene of his crime. A public gallows had been erected around the mizzenmast of HMS

Arethusa

. Before he died, Hill apologised for his actions and exhorted the authorities to exercise ‘great care and strict vigilance’ at the dockyards in future. A crowd of 20,000 watched his execution, and then the lifeless body was placed in a gibbet and rowed across the harbour entrance to Blockhouse Point and suspended there for all to see.