Stonehenge a New Understanding (48 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

The Medieval period shows up at Stonehenge in a decapitated burial and two human teeth, two dates from charcoal (AD 720–990), and other Medieval finds. This may have been the time when Stonehenge acquired

its name: “Stone Hangings” could mean a place of execution. It is possible that early churches built in the area used stones from Stonehenge. Amesbury Abbey dates back to a Benedictine foundation in AD 979 and the church at Durrington was probably built by AD 1150.

4

Excavations along the Stonehenge avenue and on the Cursus have identified cart tracks, probably from this period and later, leading from Stonehenge toward Amesbury and Durrington.

There is also plenty of debris from the early modern period of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, represented by six radiocarbon dates and by quantities of broken pottery, glass, and other artifacts. This was the period in which the earliest recorded excavations were carried out. Behind one of the trilithons (Stones 53–54), a slight rise in the ground is probably the remnants of the Duke of Buckingham’s spoil heap of 1620, though without excavation we cannot rule out the possibility that a prehistoric mound stood here.

Stone-robbing probably also continued until the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century the area next to Stonehenge was turned into a racecourse and the monument itself seems to have been a handy spot for race-goers to dispose of empty bottles and other rubbish.

20

__________

Stonehenge is, in various ways, unique. Its dressed stonework, its lintels and the remarkable distances traveled by sarsens and bluestones (even people who support the glacial-erratics hypothesis have to agree that these have come at least forty miles) are all aspects that make this a very unusual monument for Late Neolithic Britain. This might justify one considering it as a solitary edifice in splendid isolation but, to misquote John Donne, no monument is an island, entire of itself.

In the context of the surrounding landscape, the Stonehenge Riverside Project has attempted to show how Stonehenge was part of a long-lived and large complex of monuments, settlements, and landforms. We must also examine how it compares with monuments built elsewhere in Britain, to see what light these may shed on its nature and purpose.

As an example of such a comparison we can look briefly at a distinctive piece of modern architecture, the “Gherkin” (or 30 St. Mary Axe) in central London. We know that this was not beamed down from outer space or built at the command of an alien master race (bankers are, apparently, human), because we know who designed it and how. We also know what preceded it, what were the fashions of the time, and the financial and technological limits for such a building project. Yet the Gherkin stands out because of its curvilinear shape, contrasting strikingly with the standard rectilinear architecture of the City.

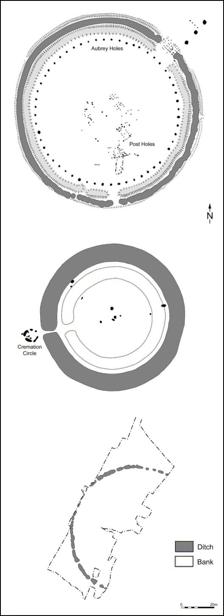

Stonehenge (in its Stage 1; top), Llandegai Henge A (middle) and Flagstones (bottom) had many features in common, including burials and large stones.

To understand why Norman Foster designed this unique structure, we need to see what influenced him. We don’t have access to his private imagination, but we do have various examples worldwide of other

buildings (Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, say, which opened in 1997) that mark the emergence of a new architectural fashion. Innovation is a constant process of comparison and contrast, reworking tradition with novelty, and expanding the resources and technology to turn dream into reality.

The earliest phase of Stonehenge, with its circular enclosure, cremation burials, and standing stones, is actually just one example of a type of monument—a cremation enclosure—that we know well from different parts of Britain. Stonehenge is, in fact, quite late in the fashion for this particular type of structure. Those who accept that the bluestones were fetched from west Wales (rather than moved to Somerset by glaciers) may not be entirely surprised to learn that Stonehenge’s closest comparison was built perhaps a century earlier, in north Wales, 140 miles from Preseli. Outside the town of Bangor, and now covered by an industrial estate, was one of Britain’s other two stonehenges.

Here at Llandegai (also written as Llandygai) were two henge enclosures, known as Henge A and Henge B.

1

The earlier of these, Henge A, was excavated in advance of development in 1966–1967: We have to write about Llandegai in the past tense now because it has all disappeared under concrete, and survives only in the excavation records. Like Stonehenge, Henge A at Llandegai was circular and also had a ditch external to its bank. At 90 meters in diameter, this henge enclosure was only slightly smaller than Stonehenge. Its ditch, however, was both wider and deeper—10 meters wide and three meters deep—and its bank was a colossal seven meters wide.

The interior of Henge A produced very few traces of Neolithic activity, although it was re-used many centuries later. The henge’s entrance faced west-southwest (though not toward the midwinter solstice sunset) and, against the inside of the bank opposite this entrance, there was a cremation burial, probably of a woman. Next to her ashes someone placed a rhyolite slab for polishing stone axes, and a cobble of crystallized tuff, probably as grave goods. Geologists cannot tell for certain from where either of these stones came, but they did travel some distance to end up here; the ax polisher is either from just west of Preseli or from the Lake District. Another pit on the west side of the henge interior

contained no burial, just a complete and unused polished ax from the Langdale quarry in the Lake District. Curiously, the bank covered a shallow pit containing Early Mesolithic pine charcoal dating to 7000 BC: Was this just a tree hole of a lightning-struck tree, or a man-made fire-pit, as it is described by the excavators?

There was a smaller ditched circle, just nine meters across, immediately in front of the entrance to Henge A. It was cut by five causeways, and all five of its ditch segments contained cremated human bones and quantities of charcoal, some of which may have come from burned planks. The burials were those of at least five adults (one of them a woman), a child, an infant, and a newborn baby. Some of these remains came from small pits inside and around the circular ditch.

A large block of hornfels (a metamorphic rock) lay within one of the cremation circle’s ditches, pushed over from a standing position. This was evidently the stump of a broken-off standing stone, but was not recognized as such by the excavators. We don’t know if more stones had been removed intact from the ditch circle without leaving evidence of their former presence.

This small circle was very similar in size to Bluestonehenge. Together with the larger henge, the site at Llandegai contained all the major elements found at Stonehenge and Bluestonehenge, just in a different pattern and without bluestones. Seven radiocarbon dates show that this proto-Stonehenge dated to somewhere within the period 3300–2900 BC, having been started before 3000 BC.

The other prototype for Stonehenge lies closer to Salisbury Plain, underneath the house of a famous Wessex author. Thomas Hardy lived in a large house named Max Gate on the eastern outskirts of Dorchester, the county town he made famous under the fictional name of Casterbridge. During building works on the house, workmen found a human burial. Although Hardy reported this discovery in the local archaeological journal, he would have had no idea that he was living on top of Wessex’s other Stonehenge.

2

Named after the other house that stood on its site, Flagstones, this henge was not found until 1987 when Wessex Archaeology excavated its western half in advance of a new bypass road.

3

Today, half of Flagstonehenge has been destroyed by the bypass and the rest is under

Max Gate’s garden. It is a bit sad that our other two stonehenges have been largely destroyed.

Flagstones’s ditch, with its gang-dug segments and diameter of 100 meters, was almost identical to that of Stonehenge. A cremated adult, an adult’s leg bone, and the incomplete skeletons of three children were found in the ditch, most of them covered by stone slabs in the same fashion as the burial found at Thomas Hardy’s house. The slabs were of sarsen and local sandstone, presumably part of a setting of standing stones that might have been demolished shortly after the ditch was dug. Fragments of sarsen, sandstone, and limestone in the fill of the ditch hinted at other stones having been broken up or taken away. Three cremation burials were found inside the henge enclosure, but none have been dated.

There is one other tie-up with Stonehenge. Thomas Hardy’s neighbors in Wareham House, just northwest of Max Gate, found a small circular pottery disc in their garden.

4

This is an incense burner, almost identical to the one accompanying one of Stonehenge’s cremation burials. They are the only two of this type ever found in Britain.

The Flagstones henge ditch was dug in the period 3300–3000 BC. Whether it had an inner bank and external counterscarp like Stonehenge or an outer bank like other henges is difficult to say, since nothing survives above ground. Flagstones had one thing that Stonehenge does not: Using flint flakes, someone in the Neolithic carved pictures into the vertical chalk sides of its ditch segments in four separate places. This art was very basic: concentric circles, a meander motif, criss-cross lines, and parallel lines—exactly the same motifs as were used on chalk plaques and Grooved Ware pottery. Unlike the peoples of other parts of Europe, Britain’s Neolithic artists seem to have been very restricted in what they could portray.

Flagstones lies at the heart of a Neolithic ritual landscape, surrounded by remains of burial mounds and three large monuments. To the east lies the henge enclosure of Mount Pleasant, with a timber circle and a newly discovered avenue leading northward to the River Frome.

5

To the west is a large pit circle at Maumbury Rings, re-used as a Roman amphitheatre.

6

To the northwest at Greyhound Yard, under

Dorchester’s Roman town center, archaeologists discovered a line of holes for Neolithic timber posts that formed a large enclosure.

7

Stonehenge, Llandegai A and Flagstones are at the top of the scale for burial enclosures in terms of size and grandeur. Archaeologists have found another sixteen such sites in other parts of Britain. Most are now destroyed, having been found in advance of development, but enough evidence was recovered for us to know that they were in use around the same time as Stonehenge.

One group of burial sites, rivaling Stonehenge in terms of numbers of cremations, lies north of Stonehenge on the River Thames at the other Dorchester. Sitting in and around a cursus, the Dorchester-on-Thames complex of circular monuments includes six pit circles and a ditched circular enclosure, all with cremations.

8

It was here that Richard Atkinson cut his archaeological teeth in the 1940s, excavating some of these pit circles before working at Stonehenge. About 170 cremations were found in these seven small cemeteries. Although none of the cremations have ever been radiocarbon-dated, long bone skewer pins and a broken stone macehead among the grave goods are identical to similar items found with burials at Stonehenge.

Since Atkinson’s discoveries at Dorchester-on-Thames, more Neolithic cremation cemetery enclosures have been found in midland England. A pit circle within a small henge ditch at Barford in Warwickshire contained cremated bones.

9

At West Stow in Suffolk, archaeologists digging a Saxon village also found a Neolithic cremation circle with a central burial and forty-nine cremations.

10

Just recently, seven cremation burials dating to 3300–3000 BC were found in two circular enclosures beneath Imperial College’s sports ground in the Colne valley, west of London.

11

Nearby at Horton, the skeleton of a woman, dating to around 2700 BC, lay buried next to a similar enclosure.

Within Wessex, there are another two Neolithic enclosures with burials. Farmer and archaeologist Martin Green found a curious circle of fourteen pits enclosing a large central hole at Monkton Up Wimborne on Cranborne Chase in Dorset.

12

In the edge of this hole, a woman and three children had been buried in a communal grave around 3300 BC. From their DNA it seems that the woman was probably the mother of one of the children, a girl. The other children were brother and sister but

unrelated to the woman with whom they were buried. Isotope analysis of tooth enamel shows that the mother grew up about forty miles away on the Mendip Hills, moved to Cranborne Chase, returned to Mendip where she gave birth to her daughter, and then returned again to the area of Dorset where all four met an untimely death. Martin Green also found a small pit-circle henge on his farm. Known as Wyke Down, it has

cremation deposits around its entrance, dating to around 2700 BC, as well as Grooved Ware pottery and a stone ax of rhyolite from just west of Preseli.

13