Stories of Faith and Courage From World War II (47 page)

Read Stories of Faith and Courage From World War II Online

Authors: Larkin Spivey

Tags: #Religion, #Biblical Biography, #General, #Spiritual & Religion

Soon after, Shumway’s life was changed forever by an exploding anti-tank mine. Advancing through the hedgerows of Normandy, he was only a yard behind a tank when it blew up. The horrendous explosion riddled him with shrapnel and thrust him into darkness. Over the following days he had to accept the fact that he was permanently blind.

The young officer spent the next two years in hospitals and rehabilitation centers, recovering from his wounds and adapting to his blindness. His progress was amazing. In 1946 he was hired by the state of Maryland as a rehabilitation counselor for the blind. He soon began visiting factories to show managers and blind workers that they could do many tasks previously thought impossible for a blind person. He became one of the most successful counselors in the nation at placing the sightless in industrial jobs. He also gradually worked up the confidence and courage to propose to his college sweetheart, Sarah Bagley. He told her, “If you’ll sort the socks and read the mail, I can do the rest.”

345

Sarah consented, and they were happily married. Shumway summed up the peaks and valleys of his life and explained the powerful source of his motivation: “I felt that my heavenly Father had blessed me and spared my life for a reason.”

346

For I tell you the truth, many prophets and righteous men longed to see what you see but did not see it, and to hear what you hear but did not hear it.

—Matthew 13:17

An Unexpected Benefit

Combat conditions had a way of dissolving denominational differences. Chaplains found themselves ministering to the men and women around them regardless of their religious affiliation or even non-affiliation. One Catholic chaplain with the 93

rd

Division found 98 percent of his troops Protestant and still worked tirelessly to provide religious support to every man. A Baptist chaplain and a Catholic chaplain worked together with the Marines going into Tarawa, and both became popular with the troops of each other’s faith. A war correspondent observed them in action and commented, “Denominational distinctions did not mean much to men about to offer up their lives.”

347

The military chaplains of World War II practiced an ecumenism born of necessity. From their combat experiences many of these chaplains also found a deeper personal faith that tended to further blur denominational differences. This cooperative spirit was a blessing to millions of men and women in uniform and would eventually bless the nation as well. Inevitably, these chaplains returned home to bring better understanding between the faiths. One historian described the phenomenon:

The American and Allied sense and hope for a better future included a perhaps unexpected benefit as chaplains returned after the war to their churches, schools, and communities. The nature of their service in combat stripped away many of the traditional icons and trappings; the faith of many chaplains was deepened by this return to the basics. There was also a significant growth in ecumenical spirit and understanding. At the battalion aid stations and the burial sites, the chaplains, regardless of their own faith, knew and used appropriately the counsel, prayers and last rites befitting the soldier who was sick, wounded, dying, or just plain afraid and exhausted.

348

There is one body and one Spirit just as you were called to one hope when you were called one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.

—Ephesians 4:46

No Self-Righteousness

Samuel Moor Shoemaker was rector of Calvary Episcopal Church in New York from 1925 to 1952. He is best remembered for his work helping formulate the Twelve Step Program for Alcoholics Anonymous. During World War II many of his sermons addressed the war effort, and his words were not always soothing to his listeners. He lashed out at the immorality that he saw in the nation, comparing America to a “spoiled child.” He did support the war effort, determining it a “grim necessity” and an opportunity for nations to again choose democracy. However, he abhorred any self-righteousness on the part of his countrymen:

No war can ever be a clear-cut way for a Christian to express his hatred of evil. For war involves a basic confusion. All the good in the world is not ranged against all the evil. In the present war, some nations that have a great deal of evil in them are yet seeking to stand for freedom… against other nations which have a great deal of good in them but yet are presently dedicated to turning the world backwards into the darkness of enslavement.

349

These words can be applied to individuals as well as to nations. Every human being has the potential for good as well as evil. And every “good” person falls short of God’s expectations. Christians especially must understand this truth. By definition, a Christian is a fallen human being whose only value comes from the grace of God and trust in Jesus Christ. There is no room for a “holier than thou” attitude toward any other human being. Samuel Shoemaker was right to remind Americans then and now that self-righteousness is even more destructive when evidenced by a nation.

Do not say to yourself, “The L

ORD

has brought me here to take possession of this land because of my righteousness.” No, it is on account of the wickedness of these nations that the L

ORD

is going to drive them out before you.

—Deuteronomy 9:4

Pass the Ammunition

On December 7, 1941, the USS

New Orleans

was moored along Berth 16 at the Navy Yard, Pearl Harbor, undergoing engine repairs while on shore power. As soon as the Japanese air attack began, the general quarters alarm sounded, and the crew scrambled to their battle stations. The sky was filled with attacking aircraft, and, in a few moments, all of the

New Orleans

’ air defense weapons were firing at a fever pitch. The ship’s chaplain, Cdr. Howell Forgy, moved about the ship, giving encouragement to the men. He himself was inspired by a group of sailors passing shells to one of the five-inch gun mounts:

The big five-inch shells, weighing close to a hundred pounds, were being pulled up the powerless hoist by ropes attached to their long, tube-like metal cases. A tiny Filipino messboy, who weighed little more than the shell, hoisted it to his shoulder, staggered a few steps, and grunted as he started the long, tortuous trip up two flights of ladders to the quarterdeck, where the guns thirsted for steel and powder. A dozen eager men lined up at the hoist. The parade of ammunition was endless, but the cry kept coming from topside for more, more, more… The boys were putting everything they had into the job, and it was beginning to tell on them… Minutes turned to hours. Physical exhaustion was coming to every man in the human endless-chain of that ammunition line. They struggled on. They could keep going only by keeping faith in their hearts.

I slapped their wet, sticky backs and shouted, “Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.”

*

This phrase soon became well known and was incorporated into a song by Frank Loesser. Reflecting a more innocent age and the religious character of America at that time, it became a popular hit. The song told the story of a chaplain who laid aside his Bible to man the guns, while shouting what was to become one of the most famous phrases of World War II.

There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under heaven… A time to tear and a time to mend, A time to be silent and a time to speak, A time to love and a time to hate, A time for war and a time for peace.

—Ecclesiastes 3:1, 78

World War II Navy recruiting poster. (National Archives)

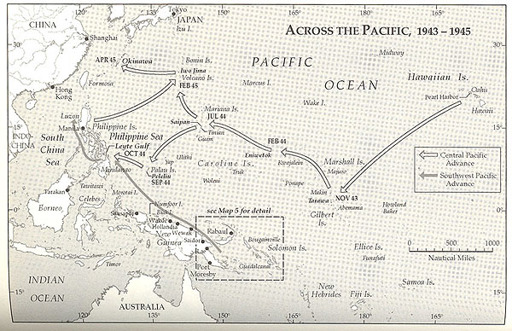

The Central Pacific Campaign

Adm. Isoruku Yamamoto, the architect of the Japanese triumph at Pearl Harbor, warned his superiors early in the war that if the conflict lasted more than a year he would not be able to guarantee success against the United States. In 1943, his worst nightmare was realized as America’s industrial might began to show itself in the Pacific. By that time, the U.S. 5

th

Fleet was operating with six heavy Essex class aircraft carriers, thirteen smaller carriers, twelve battleships, and large numbers of cruisers, destroyers, and support ships. Commanding this armada was the hero of Midway, Vadm. Raymond Spruance. The spearhead of the fleet was its four Fast Carrier Task Groups, each with four aircraft carriers and an escort of supporting surface ships. The ground combat element was the V Amphibious Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Holland M. Smith, affectionately known as “Howlin’ Mad” by the Marines under him. Having anticipated the coming battles in the Pacific for more than a decade, the Marines were ready with the equipment and tactics for an island-hopping campaign against defended beaches.

After considerable debate between Army and Navy planners, the Joint Chiefs decided that priority in the Pacific would go to a Navy and Marine Corps drive directly at Japan, while MacArthur’s Army forces would continue their advance through New Guinea toward the Philippines. Step one of the Central Pacific campaign would be the coral atoll of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands.

The main objective at Tarawa was the tiny two-mile-long island of Betio, the only fortified position on the atoll and site of an airfield. On November 21, 1943, five thousand Marines of the 2

nd

Marine Division made a difficult landing on the lagoon side of the island across a wide expanse of shallow reef. In three days of savage fighting more than one thousand Marines were killed attacking strongly fortified positions that had proven impervious to inaccurate naval and air bombardment. Bunkers with six-foot-thick roofs made of logs, sand, and corrugated iron had to be assaulted by individual squads with rifles, hand grenades, and satchel charges. Valuable lessons were learned at Tarawa that would benefit upcoming operations, including the necessity of longer and more accurate pre-assault fire support.

As U.S. forces captured the Marshall Islands in February 1944, the Japanese were forced to a new inner perimeter stretching from the Mariana Islands to the Palaus and western New Guinea. The garrisons east of this line were given the suicidal mission of sacrificing themselves to make the U.S. advance as slow and costly as possible. The assaults on Saipan and Peleliu were accordingly contested to almost the last man. D-Day on Saipan was June 15, 1944, nine days after the invasion of France. Marine and Army units sustained more than sixteen thousand casualties overcoming the thirty-two thousand defenders. The attack on Peleliu in September proved to be the costliest amphibious operation in history, with forty percent casualties.

350

In conjunction with these land operations the Pacific Fleet fought a series of important naval engagements that further reduced Japanese military strength in the Pacific. In one two-day period U.S. carrier aircraft and submarines inflicted a crippling blow to Japanese naval air power, destroying three hundred aircraft and three carriers in the Philippine Sea. These operations in the Central Pacific in 1944 brought the war ever closer to mainland Japan. Air bases in the Marianas enabled long-range bombers to reach Tokyo, while new naval bases prepared the way for the long-awaited U.S. return to the Philippines.