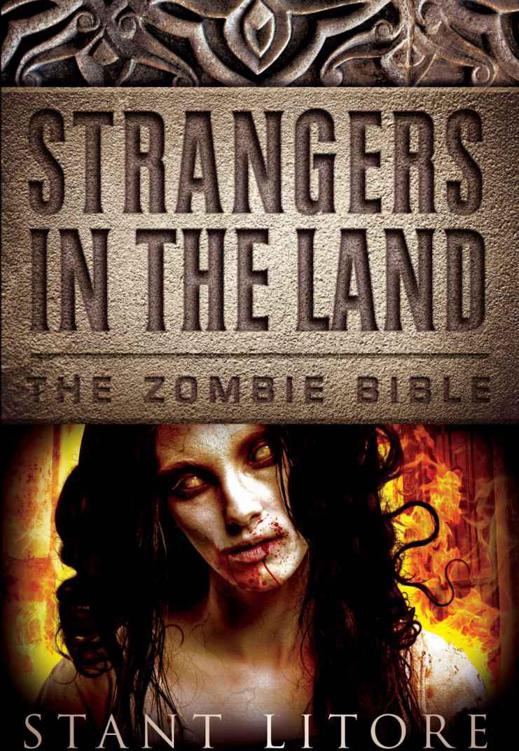

Strangers in the Land (The Zombie Bible)

Read Strangers in the Land (The Zombie Bible) Online

Authors: Stant Litore

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2012 Daniel Fusch

Stant Litore is a pen name for Daniel Fusch.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by 47North

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN-13: 9781612183923

ISBN-10: 1612183921

for my daughters River and Inara

may their lives be full and free

The Man Who Defended His Cattle

Hardly Daring To Close Her Eyes

Part 4: Along the Tumbling Water

I

N THE

thirteenth century BC, several wandering tribes of Hebrews were crossing the desert. They were a young and vigorous people, flushed with life. Few of them had ever seen a walking corpse.

They were freshly displaced from the fertile fields of the Nile, where the dead were carefully contained; indeed, many Hebrew workers had broken their backs in hard labor, making or hauling brick to build the high tombs in which the cities of Kemet (that land the Greeks called Egypt) housed their dead. Those of Kemet cherished the memory of their dead and did all they could to send the deceased to the judgment hall well prepared.

There, the recently deceased handed its heart to the gods, to be weighed in scales against the feather of virtue. Often, the heart, burdened by the evils of this life, proved heavier than the feather. Then, the people of Kemet believed, the soul was cast back into the body. Deprived of the fruitful fields beyond death, it rose from its sarcophagus in a mind-devouring hunger.

The bodies of the dead must be securely entombed against this possibility. Hoping that any wakeful dead might yet find peace, the people of Kemet inscribed the insides of the tombs with hieroglyphics and magnificent art—spells and prayers and histories, everything that a risen corpse might need to remember who it had been. Perhaps, if a corpse could be made to remember the life it had lived and its hope of new life beyond death’s river, the spirit might return to its gray eyes and it might offer an acceptable sacrifice and

atonement using the incense, fruits, and ornate vessels of fine drink that its relatives had left with it in the tomb. Then lie down in the sarcophagus and return to the hall of judgment with a lightened heart. So those of Kemet hoped as they slid closed the massive doors of the tombs.

In our own era, several unwary archaeologists have slid open those same doors to find themselves food for the cursed and hungry dead—a testament to the utter forgetfulness of death and the smallness of the human voice, which even with its strongest stories and most beautiful pictographs cannot yet reach across death’s river to bring messages or remembrance to the lost.

In time, Kemet adopted other practices for securing a successful journey across death’s river. The brains of the dead they scooped free of the skull, and the other organs too, placing them in canopic jars. Mummification effectively prevented resurrection; the bodies were now but hollow shells closely enshrouded in linens. In time, the plague became virtually unknown in Kemet. Yet that cultural legacy of a pronounced concern for the well-being of the newly dead persisted. Over the centuries, the brick tombs grew greater and more magnificent, and many laborers—both Hebrews and men of other ethnicities—died in the toil of making them.

In caring so meticulously for their own dead, the people of Kemet oppressed bitterly the living members of other tribes, and the tale of the revolt of the tribes is among the most dramatic of the stories that come down to us from our spiritual ancestors. The Hebrews have left us many folktales and songs that tell of the coming of their Lawgiver and his confrontation with the Pharaoh, their liberation from oppression, and their march into the wilderness to find their own land and their own deity.

The story is well known and frequently retold. Yet most modern storytellers end their tales and let their voices fall still after the celebratory departure, the exodus from Kemet; it is hard for us to gaze steadily at the dark years in the desert and the trials

that turned a frightened people of former slave workers into the hardened, efficient, and even brutal tribes that a generation later invaded fertile Canaan, slaughtering many of its people and setting up their tents in the valleys near the burned and smoking towns.

What happened to these people in the desert?

Their exodus from a land lush with food yet dark with oppression into barren hills with few oases strikes us as both magnificent and naïve, perhaps in equal measure. The Hebrews starved in the desert, and thirsted, and even lamented the loss of a life of enslavement that at least had not required any of them to be responsible for their own provision. Better to be oxen pulling brick than be men, some of them cried. It is too hard to be men. The women offered their own complaints: along the Nile, their more lovely daughters may have been prey for lusty overseers, but at least they had been fed and clothed.

This season of innocent misery came to an unanticipated and terrible end one night when the dead stumbled, groaning, out of the rocks and canyons and fell upon the tents. We do not know where these dead came from, or why they were so many. Dead have been known to travel together en masse, shambling slowly like animal herds across an empty landscape until they encounter food. It is possible some other tribe had succumbed to the illness and had slouched into the dry hills without direction or destination, there to wait for years or even centuries until drawn by the noise of the Hebrew camp.

We do know that the death toll was severe. Even if we accept the Hebrews’ written memories as the most extravagant of exaggerations, the loss of life must have been catastrophic. When dawn came, the Hebrews faced the hard reality that many of their people

had been eaten and many others bitten. Some of the latter were already lurching unsteadily to their feet, their hands reaching to clutch at the survivors.

How the Lawgiver ended the pestilence is a narrative that I will refer to elsewhere, not here; it is at any rate no story to tell after dark. More important is the way of life the survivors adopted in their fierce intent never to suffer such a crisis a second time.

That time of terror in the wilderness redefined how the Hebrews understood their world and their duties within it. They saw themselves now as alone—desperately alone in a complex and threatening world they had been taught to believe was simple; in the empty desert they had few things to rely on. In their need for certainty, they established a Covenant with the God they had encountered in the desolate wastes, and they chiseled the first words of their Pact into tablets of hard stone, which they then kept with them always in a sacred Ark. In Kemet, they had seen contracts written on scrolls of papyrus, a vegetable material that perished if exposed to moisture; the desert demanded that a covenant as important as this one be recorded on some substance less fragile. Only a contract written into stone that would last as long as the earth could assure them of its reliability.

Among other exacting rules, the Covenant demanded a sharp separation between the living and the dead. The living were to clean their hands and arms up to the elbows before and after touching any dead meat, and the meat of some animals could not be touched at all; they were not to touch with their naked hands the body of any dead man or woman; they were not to leave any dead body unburied, for any reason. The punishments for breaking the Covenant were severe, even as the promised reward for keeping it

was great: an eternal inheritance in a clean and fertile land and divine protection from the hungry dead.