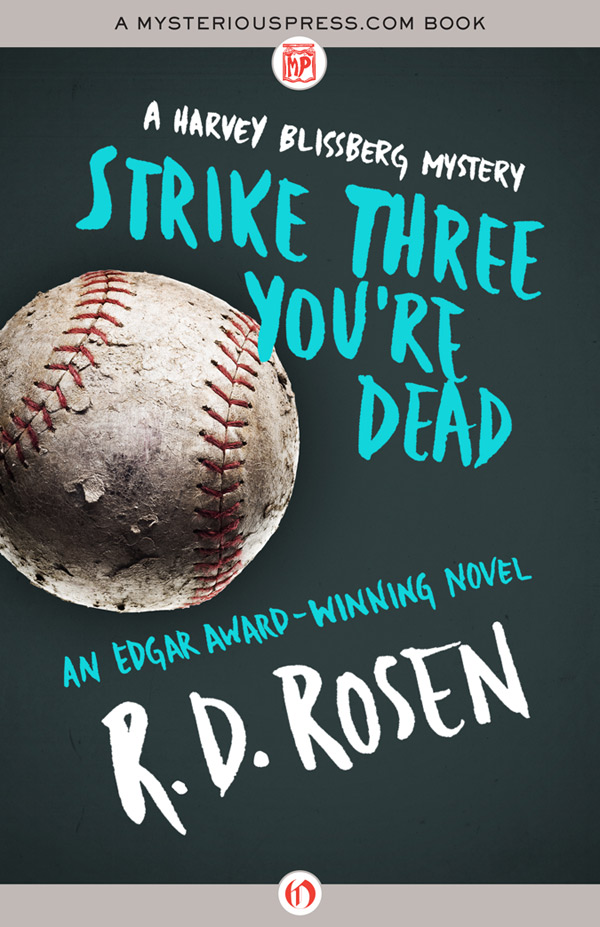

Strike Three You're Dead

Read Strike Three You're Dead Online

Authors: R. D. Rosen

A Harvey Blissberg Mystery

R. D. Rosen

A MysteriousPress.com

Open Road Integrated Media

Ebook

In memory of Ann Hall

THE PROVIDENCE JEWELS

Owner and President: Marshall Levy

Manager: Felix Shalhoub

Public Relations Director: Buzzy Stanfill

Stadium: Rankle Park (seating capacity—37,000)

Colors: Emerald green, black, and white

Coaching Staff

Timothy Bayman, pitching coach

Anthony Cantalupa, third base coach

Campy Strulowitz, first base coach and batting instructor

Arky Bentz, trainer

Duncan Frye, clubhouse manager

ROSTER

No. Name, Position, Age, Birthplace

14 BATTLE, Cleavon IF 29 Bakersfield, CA

49 BLISSBERG, Harvey OF 30 Boston, MA

6 BYERS, Lester IF 33 Syracuse, NY

15 CHARNESS, David C-OF 23 Cloquet, MN

10 EPPICH, Randall C 26 Allentown, PA

22 HOSMER, Robert OF 21 Spanish Fork, UT

12 LUGO, Luis IF 22 Fajardo, P.R.

9 MANOMAITIS, Charles IF 24 Fairlee, VT

7 PENZENIK, Charles IF 24 Sacramento, CA

3 RAPP, John OF 29 Pueblo, CO

11 SALTA, Rodney IF 25 Cali, Colombia

19 SMITH, Clyde C 34 Belleville, IL

25 STILES, Richard OF 29 Lima, OH

8 VEDRINE, Angel IF 23 Barquisimeto, Venezuela

24 WILTON, Steven OF 27 Bessemer, AL

Pitchers

17 VAN AUKEN, Daniel LHP 26 New Britain, CT

39 CROP, Stanley RHP 25 Rosenberg, TX

29 FURTH, Rudolph LHP 28 Palmyra, WI

40 MARLETTE, Marcus RHP 25 Lumpkin, GA

48 O’DONNELL, John RHP 24 Cambridge, MD

32 OTHER, Donald LHP 31 Moline, IL

55 POTTER-LAWN, Andrew LHP 26 Bishop’s Stortford, England

50 STORELLA, Edward RHP 22 Manhattan, KA

52 WAGNER, Robert RHP 27 Roanoke, VA

34 WEATHERHEAD, James LHP 22 Los Angeles, CA

I

T’S WHEN YOU’RE GOING

good that they throw at your head.

Harvey Blissberg had been starting center fielder for the Boston Red Sox for five seasons, had two years left on a new three-year contract, and had just engaged the services of an interior decorator for his recently acquired Back Bay condominium when the team abruptly left him unprotected in the expansion draft over the winter. As a direct result of this insult, he became the property of the Providence Jewels, the latest addition to the American League Eastern Division. At an age when most of his contemporaries were winning their first big promotions, Harvey was obliged to pick himself up and start over with a team composed largely of cast-offs, players of proven mediocrity, and a few arrogant rookies thrown in just to remind him that, as far as baseball was concerned, he was no longer a young man.

Last year, with the Red Sox, he had considered himself in his prime. Now he felt like someone detained at the border before being allowed to pass over into the rest of his life.

Providence, Rhode Island, looked like a place you ended up when they kicked you out of everywhere else. It was too small and not nervous enough to be a city, as Harvey understood the term, but it was too big to be anything else. It seemed to consist entirely of outskirts—a sad city where a Mercedes or a tuxedo was as incongruous as a camellia bush in a vacant lot. At night, the streets of Providence were as empty as Rankle Park’s upper deck on any game day.

Actually, the lower grandstands were never that crowded either. The Jewels’ aging brick and concrete home, built in the twenties and enlarged a few times for a succession of short-lived minor league teams, dominated a drab neighborhood that discouraged traffic, let alone baseball fans. With its odd assortment of gray facades, turrets, and archways, Rankle Park resembled a rusting battleship docked among shoe factories, textile mills, and warehouses whose tenants had migrated in the seventies to the more congenial Sun Belt.

The fans weren’t the only ones who thought they deserved better. When visiting clubs first saw the park, the players tended to react with the polite dismay of people invited to dinner at a house that hadn’t been cleaned in weeks. The proposed new stadium outside town didn’t look as though it would materialize for another two years, if at all. That the team playing in so tarnished a setting was called the Jewels was an irony seldom lost on the sports-writers who fought for elbow room in the battered press box over home plate. Still, there was logic to the name: the team’s owner and president, Marshall Levy, was the founder of Pro-Gem, the biggest costume jewelry concern in a state that had the biggest costume jewelry industry in the country. Levy had ignored the argument that “Jewels” was an unfortunate name for the team of a town where most of the gems were phony.

Even though you had to wonder—and Harvey Blissberg was among those who did—what the baseball commissioner and team owners had been thinking when they awarded a franchise to Providence, the Jewels had exceeded expectations. It was August 28, and with their 63-and-66 record, the Jewels could glance down in the Eastern Division standings and see Detroit and Toronto.

As for Harvey, at the age of thirty he was somehow enjoying his best season ever. His .309 batting average was more than 40 points above his modest career average, and he led Providence in batting, doubles, and—his legs felt five years younger than the rest of him—stolen bases. He was throwing around a lot of leather in center field. And as a bonus, he and Mickey Slavin—some said she was the best and most attractive television sportscaster in Providence—were finally an item.

These unexpected blessings made Harvey slightly uncomfortable. Having been burned once, he had the distinct feeling that someone was bound to start throwing at his head again. But as he stood with bat in hand behind the batting cage an hour before Tuesday night’s game with Chicago, the only threat to his well-being came in the form of a vaguely familiar voice.

“Hey, Ha’vey, whaddya say, guy? Come ova heah a sec.” It was one of those New England accents that produces

r

’s when they aren’t called for, and drops them when they are.

Harvey turned toward the box seats. Ronnie Mateo stood in his usual pre-game spot in the first row by the Jewels’ dugout, one spindly leg poised on top of the low wall separating the seats from the field. He was a thin man in his thirties with tightly curled black hair, a long face that looked like a blanched Brazil nut, and a taste for colorful double-knits and two-tone imitation snakeskin casuals. He was well known to many of the Jewels, to whom he tried to sell dubious merchandise from time to time. Occasionally he succeeded, which was why Chuck Manomaitis, the Providence shortstop, had shown up in the clubhouse a month before with a dozen digital traveling alarm clocks—still in their boxes next to the Desenex on the shelf of his locker.

Ronnie had never approached Harvey before. Harvey liked to think of himself as the kind of person who didn’t look as if he needed a lot of cheap traveling alarm clocks.

“Professah! Hey, Professah,” Ronnie shouted. “Come ova heah.”

Harvey, who owned five Harris tweed sports jackets and read hardcover books on road trips, had been slapped with the nickname in his rookie year. It amused him because his older brother Norman was a real professor—of English, at Northwestern. “Professor” implied a clubhouse intimacy that Harvey was not aware Ronnie Mateo enjoyed with him. He finally ambled over to the box seats, not looking at Ronnie until he was standing in front of him.

“Whaddya want?” Harvey said. “You’re a little too old for autographs.”

“It’s not what you can do me, Professor. It’s what I can do you.” Ronnie bent over the leg up on the wall and smoothed a tan sock with both palms. “You interested in a gross of necklaces, real nice merch, the kind that every month’s got a different stone?”

Harvey narrowed his eyes. “Have we met?”

“We need an introduction? I’m pretty friendly with a lot of the ball players.”

“All the same. Harvey Blissberg,” he said, extending his hand.

Ronnie shook hands, pronouncing his name so it sounded like “raw knee,” then flicked something that wasn’t there off a brown and gold shoe. “A hundred forty-four necklaces, twelve of each month, each month a different stone. This is a very nice item.” He pulled a handful of necklaces out of his jacket pocket and held them in Harvey’s face.

Harvey rubbed some pine tar on the shaft of his bat with the rag. “What the hell would I do with them?”

“Now that all depends. If I was you, Professor, I’d give ’em to your lady friends.” His smile showed a fringe of tiny teeth.

“Yeah, well, I’m about a hundred and forty-three-and-a-half girlfriends short. Besides, all the women I know were born in February or October.”

“So give ’em to your fans. Look, this is quality merch.” Ronnie ran a thumbnail coated with clear polish over a red stone. “I wouldn’t make this offer to anybody.”

“And I don’t blame you,” Harvey said, starting to turn. “See you around.”

“I wouldn’t make this offer to anybody but you, Professor,” Ronnie said again. In the row behind him, an elderly usher in a jacket with torn epaulets was showing a couple to their box seats.

“Where’d you come up with a gross of necklaces, anyway?”

“Here and there,” Ronnie said.

“That wouldn’t be the kind of junk Marshall Levy makes, would it?”

Ronnie’s face dimmed at the mention of the Jewels’ owner, and he carefully put the necklaces back in his pocket. His little black eyes wandered off behind Harvey toward the batting cage. “Gee, that kid Wilton can sure hit,” he said. “You’re hitting good, too, this year, Professor.”

Harvey pivoted away from him again. “I’ll see you around.”

“They warned me you was a standoffish guy,” Ronnie said to his back.

Harvey kept walking, but the voice stopped him after a few yards.

“Hey, Professor. What month your mother born in?”

Harvey turned to him. “February,” he said.

Ronnie produced a glittering tangle of necklaces, extricated one, and lobbed it at Harvey. “That’s an ametist, Professor,” he called out. “For February. Tell your mother it’s from Ronnie Mateo, who’s a big fan of her son.”

Harvey walked back toward the cage. When you wore a major league baseball uniform, sooner or later everyone wanted a piece of you. It was a matter of pride to Harvey that after six years of being approached by hustlers, hot-shot investment counselors, and all the shades of manipulators in between, there weren’t any pieces of him missing.

When Rudy Furth, the Jewels’ relief pitcher and Harvey’s roommate on the road, came up to him at the batting cage, Harvey was idly running the necklace through his fingers.

“I’ve jerked off in front of more people than this,” Rudy said. He was twenty-eight, but he looked like a senior in high school.

Harvey scanned the stands. The gate this evening would be lucky to hit the dismal average. “Yeah,” he said, “and here I am playing the best ball of my career.”

“At least someone on the team is.” Rudy blew a pink bubble with his gum and sucked it back noisily into his mouth. “A gift from Ronnie Mateo?”

Harvey looked at the necklace in his fingers as if surprised to find it there. “Yeah, he tried to sell me some. What’s his story?”

“He tried to sell me some color TVs once.”

“What is he—some kind of low-grade fence?”

Rudy shrugged. “Who knows? I told him to buzz off. Even I know enough to stay away from him.”