Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (6 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

But time has dimmed the glitter of Safiye’s jewel, and its walls and windows are blackened by the soot from the ferries which berth nearby. Then, too, Yeni Cami was built after Ottoman architecture had passed its peak, and it fails to achieve the surpassing beauty of Sinan’s masterpieces of the previous century. Nevertheless, it is still a fine and impressive structure, and its graceful silhouette is an adornment to the skyline of Stamboul.

Yeni Cami, like many of the other imperial mosques in Stamboul, represents a variation on the basic plan of the great church of Haghia Sophia. Whereas in Haghia Sophia the central dome is flanked by two semidomes along the longitudinal axis, Yeni Cami is cruciform, with semidomes along both axes and smaller domes at each of the four corners. The resultant silhouette is a graceful flowing curve from dome to semidomes to minor domes, a symmetrical cascade of clustering spheres. The north and south façades of the building have two storeys of porticoed galleries which, with the pyramidal arrangement of the domes, give a light and harmonious effect. The two minarets each have three

ş

erefes, or balconies, with superb stalactite carving. In olden times the call to prayer was given by six müezzins, one to each

ş

erefe, but now they have been replaced by a single loudspeaker attached to a soulless tape-recorder.

Like all of the other imperial mosques in Stamboul, Yeni Cami is preceded by a monumental courtyard, or avlu. The courtyard is bordered by a peristyle of 20 columns, forming a portico which is covered with 24 small domes. At the centre of the courtyard there is a charming octagonal

ş

ad

ı

rvan, or ablution fountain, one of the finest of its kind in the city. At the

ş

ad

ı

rvan, which means literally “free-flowing fountain”, the faithful would ordinarily perform their abdest, or ritual ablutions, before entering the mosque to pray. But in Yeni Cami the

ş

ad

ı

rvan serves merely a decorative purpose, and the ritual washings are performed at water-taps along the south wall of the mosque.

The stone dais on that side of the courtyard which borders the mosque is called the son cemaat yeri, literally the place of last assembly. Latecomers to the Friday noon service when the mosque is full often perform their prayers on this porch, usually in front of one of the two niches which are set to either side of the door. The façade of the building under the porch is decorated with tiles and faience inscriptions forming a frieze. The two central columns of the portico, which frame the entrance to the mosque, are of a most unusual and beautiful marble not seen elsewhere in the city.

The interior of Yeni Cami is somewhat disappointing, partly because the mosque is darkened by the soot which has accumulated on its windows. What is more, the tiles which decorate the interior are of a quality inferior to those in earlier mosques, the celebrated Iznik tiles of the period 1555–1620. Nevertheless, the interior furnishings of the mosque are quite elegant in detail. The most important part of the interior of Yeni Cami, as in all mosques, is the mihrab, a niche set into the centre of the wall opposite the main entrance. The purpose of the mihrab is to indicate the k

ı

ble, the direction of Mecca, towards which the faithful must face when they perform their prayers. (In Istanbul the direction of the k

ı

ble is approximately south-east, but for convenience we will refer to it as east, the general orientation of the Christian churches of the city.) In the great mosques of Istanbul the mihrab is invariably quite grand, with the niche itself made of finely carved and sculptured marble and with the adjacent wall sheathed in ceramic tiles. The mihrab in Yeni Cami is ornamented with gilded stalactites and flanked with two enormous golden candles, which are lighted on the holy nights of the Islamic year. To the right of the mihrab we see the mimber, or pulpit, which is surmounted by a tall, conical-topped canopy carried on marble columns. At the time of the noon prayer on Friday the imam, or preacher, mounts the steps of the mimber and pronounces the weekly sermon, or hutbe. To the left of the mihrab, standing against the main pier on that side, we see the kürsü, where the imam sits when he is reading the Kuran to the congregation. And to the right of the main entrance, set up against the main pier at that end, we find the müezzin mahfili, a covered marble pew. During the Friday services and other ceremonial occasions the müezzin kneels there, accompanied perhaps by a few other singers, and chants the responses to the prayers of the imam. During these formal occasions of worship, the faithful kneel in long lines and columns throughout the mosque, following the prayers attentively and responding with frequent and emphatic amens. The women, who take no part in the public prayers, are relegated to the open chambers under the gallery to the rear of the mosque.

The mosque interior is overlooked by an upper gallery on both sides and to the rear, with the two side galleries carried on slender marble columns. At the far corner of the left gallery we see the sultan’s loge, or hünkâr mahfili, which is screened off by a gilded grille so that the sultan and his party would be shielded from the public gaze when they attended services. Access to the sultan’s loge is gained from the outside by a very curious ramp behind the mosque. This ramp leads to a suite of rooms built over a great archway; from these a door leads to the hünkâr mahfili. This suite of rooms included a salon, a bedchamber and a toilet, with kitchens on the lower level, and served as a pied-à-terre for the Sultan.

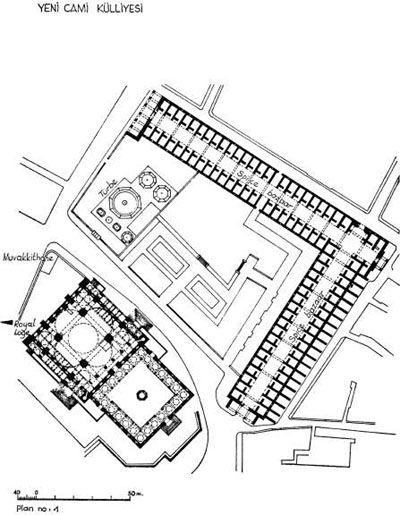

Yeni Cami, like all of the imperial mosques, was the centre of a whole complex of religious and philanthropic institutions called a külliye. The original külliye of Yeni Cami included a hospital, a primary school, a public bath, two public fountains, a mausoleum and a market, whose profits were used towards the support of the other institutions in the külliye. The hospital, the primary school and the public bath have been destroyed but the other institutions remain.

The market of Yeni Cami is the handsome L-shaped building to the south and west of the mosque. It is called the M

ı

s

ı

r Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

, or the Egyptian Market, because it was once endowed with the Cairo imposts. In English it is more commonly known as the Spice Bazaar, for in former times it was famous for the spices and medicinal herbs which were sold there. Spices and herbs are still sold there today, but the bazaar now deals in a wide variety of commodities, which makes it perhaps the most popular market in the city. In the domed rooms above the arched entrance there is a very picturesque and excellent restaurant called Pandelis, or the M

ı

s

ı

r Lokantas

ı

, which serves both Turkish and western dishes.

The mausoleum, or türbe, of the Yeni Cami külliyesi is the handsome building at the eastern end of the garden of the Egyptian Bazaar. Here are buried the foundress of Yeni Cami, Turhan Hadice, her son, Mehmet IV, and several later sultans, Mustafa II, Ahmet III, Mahmut I, Osman III and Murat V, along with countless royal princes and princesses. The small building to the west of the türbe is a kütüphane, or library, which was built by Turhan Hadice’s grandson, Ahmet III, who ruled from 1703 till 1730. Ahmet III was known as the Tulip King, and the period of his reign came to be called the Lale Devri, the Age of Tulips, one of the most charming and delightful eras in the history of old Stamboul. It is entirely fitting that the tomb of the Tulip King should look out on a garden which is now the principal flower-market of the city.

Directly opposite the türbe, at the corner of the wall enclosing the garden of the mosque, is a tiny polygonal building with a quaintly-shaped dome. This was the muvakkithane, or the house and workroom of the müneccim, the mosque astronomer. It was the duty of the müneccim to regulate the times for the five occasions of daily prayer and to announce the exact times of sunrise and sunset during the holy month of Ramazan, beginning and ending the daily fast. It was also his duty to determine the date for the beginning of a lunar month by observing the first appearance of the sickle moon in the western sky just after sunset. The müneccim, like most astronomers of that period, also doubled as an astrologer, and the most able of them were often asked to cast the horoscopes of the Sultan and his vezirs. In more recent times the müneccim often served as the watch repairman for the people in the local neighbourhood.

At the next corner, on the same side of the street as the türbe, is the sebil of the Yeni Cami külliyesi. The sebil is an enclosed fountain which was used to distribute water free to thirsty passersby. Sebil means literally “way” or “path”, and to construct a sebil was to build a path for oneself to paradise. There are some 80 sebils still extant in Istanbul, although that belonging to Yeni Cami is one of the very few still serving something like its original purpose (bottled water is now sold there rather than given away free). These sebils are often extremely attractive, with ornate bronze grilles and sculptured marble façades. The architects who designed the pious foundations of Istanbul were quite fond of using sebils to adorn the outer wall of a külliye, particularly at a street-corner. Although most of the sebils in town no longer distribute free water, they still gratify passers-by with their beauty. For that reason they should still provide a path to paradise for their departed donors.

TOWARDS THE FIRST HILL

The next street to the right beyond the sebil is a narrow alley which leads to the hamam, or public bath of Y

ı

ld

ı

z Dede. This gentleman, whose name was Necmettin, was an astrologer (Y

ı

ld

ı

z = Star) in the court of Sultan Mehmet II and won fame by predicting the fall of Constantinople from the celestial configurations at that time. According to tradition, Y

ı

ld

ı

z Dede built his hamam on the site of an ancient synagogue, probably one belonging to the Karaite Jews. The present bath, however, appears to date only from the time of Sultan Mahmut I, about 1730. It is now known as Y

ı

ld

ı

z Hamam

ı

, but of old it was called Ç

ı

f

ı

t Hamam

ı

, the Bath of the Jews.

A little farther down the main street (Hamidiye Caddesi) and on the same side we come to the türbe of Sultan Abdül Hamit I. During his reign, from 1774 till 1789, the Ottoman armies suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of the Russians and the Empire began to lose its dominions in the Balkans. By that time the reputation of the once proud Ottomans had sunk so low that Catherine the Great was heard to remark to the Emperor Joseph: “What is to become of those poor devils, the Turks?” Buried alongside Abdül Hamit in this türbe is his son, the mad Sultan Mustafa IV. Mustafa, the second imperial lunatic to bear that name, was responsible for the murder of his cousin, Selim III, and nearly succeeded in bringing about the execution of his younger brother, Mahmut II. Mustafa was eventually deposed on 28 July 1808 and was himself executed three months later.

Behind the türbe there is a medrese, or theological school, also due to Abdül Hamit I. The türbe and medrese were part of a külliye built for that sultan in 1778 by the architect Tahir A

ğ

a. The remainder of the külliye has since disappeared except for the sebil, which has been moved to a different site.

A short distance beyond the türbe, Hamidiye Caddesi intersects Ankara Caddesi, a broad avenue which runs uphill. Ankara Caddesi follows approximately the course of the defence-walls built by Septimius Severus at the end of the second century A.D., a circuit of fortifications that extended from the Golden Horn to the Sea of Marmara along the course of the present avenue, enclosing the ancient town of Byzantium. Looking to the left at the intersection we see the recently refurbished Sirkeci Station, the terminus of the famous Orient Express, which made its first run through to Istanbul in 1888. There is an antique locomotive dated 1874 on view outside the station.

We now turn right along Ankara Caddesi and follow it as it winds uphill. The district through which we are now strolling is the centre of the publishing world of Istanbul; all of the major newspapers and magazines have their presses and offices here. There are also a number of bookshops along the avenue, with one of them built over a Byzantine basement that can be seen at the back of the store. Ahead and to the left we see the building that houses the Istanbul Governor’s Office. The view down Hükümet Kona

ğ

ı

Sokak past the governor’s office is a good perspective of the west façade of Haghia Sophia.