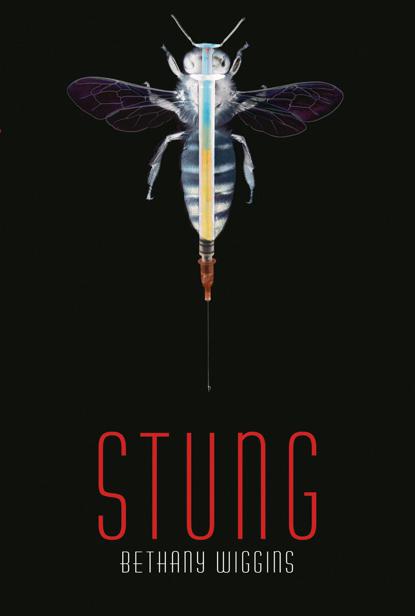

Stung

Authors: Bethany Wiggins

For Suzette Saxton and Lance Corporal Erin Owings, because

love is the power of a true warrior, and those who are deemed weak,

by its divine nature are made strong

Chapter 1

I don’t remember going to sleep. All I remember is waking up here—a place as familiar as my own face.

At least, it should be.

But there’s a problem. The once-green carpet is gray. The classical-music posters lining the walls are bleached, their brittle corners curling where the tacks are missing. My first-place ribbons are pale blue instead of royal. My sundresses are drained of color. And my bed. I sit on the edge of a bare, sun-bleached mattress, a mattress covered with dirt and twigs and mouse droppings.

I turn my head and the room swims, faded posters wavering and swirling against grimy walls. My head fills with fuzz, and I try to remember when my room got so filthy, since I vacuum

and dust it once a week. And why is the mattress bare, when I change the sheets every Saturday? And where did my pillows go?

My stomach growls, and I push on the concave space beneath my ribs, against the shirt sweat-plastered to my skin, and try to remember the last time I ate.

Easing off the bed, I stand on rubbery legs. The carpet crunches beneath my feet, and I look down. I am wearing shoes. I have been

sleeping

in shoes—old-lady white nurse shoes. Shoes that I have never seen before. That I have no memory of pulling onto my feet and tying. And I am standing in a sea of broken glass. It glitters against the filthy, faded carpet, and I can’t remember what broke.

A breeze stirs the stifling air, cooling my sweaty face, and the gauzy curtains that hide my bedroom window lift like tattered ghosts. Jagged remnants of glass cling to the window frame, and a certainty creeps into my brain, seeps into my bones. Something is wrong—

really

wrong. I need to find my mom. On legs barely able to hold my weight, I stumble across the room and to the doorway.

Sunlight streams through the bedroom windows on the west side of the house, lighting the dust in the hallway. I peer into my brother’s room and gasp. His dinosaur models are broken to bits and strewn across the faded carpet, along with the Star Wars action figures he’s collected since he was four years old. I leave his doorway and walk to the next door, to my older sister’s room. College textbooks are on the floor, their pages torn and

scattered over the filthy carpet. The bed is gone and the mirror above the bureau is shattered.

Dazed, I walk through sunlight and dust, down the hall, trailing my fingers along the paint-peeling wall to Mom’s room.

Her room is just like the other rooms. Faded. Filthy. Broken windows. Bare mattress. And a word I don’t want to think about but force myself to admit.

Abandoned

.

No one lives here. No one has lived here for a long while. But I remember Dad tucking me in a few nights ago—into a clean bed with crisp sheets and a pink comforter. In a room with a brand-new London Symphony Orchestra poster tacked to the wall. I remember Mom checking to see that I dusted the top of my dresser. I remember Lissa leaving before sunrise for school. And Jonah’s Star Wars music blaring through the house.

But somehow I am alone now, in a house where my family hasn’t been in a really long time.

I run to the bathroom and slam the door behind me, hoping that a splash of icy water will clear my head and wake me to a different reality. A normal reality. I turn on the water and back away from the sink. It has dead bugs and a rotting mouse in it, and nothing comes out of the rust-speckled faucet. Not a single drop of water. I brace my hands on the counter and try to remember when the water stopped working. “Think, think, think,” I whisper, straining for the answers. Sweat trickles down my temple and I come up blank.

In the cracked, dust-coated mirror, I see a reflection, and the

thought of being abandoned slips away. I am not alone, after all. She is tall, with long, stringy hair, and gangly, like she’s just had a growth spurt. She looks like my older sister, Lissa. She is Lissa. And maybe she knows what’s going on.

“Lis?” I ask, my voice scratchy-dry. I turn around, but I’m alone. Turning back to the mirror I carefully wipe away the dust with my hand. So does the reflection.

My

muddy eyes stare back from a hollow face, but it’s not my face. I take a step away from the mirror and stare at the reflection, mesmerized and confused. I slide my hands over the contours of my lanky body. So does the reflection. The reflection is mine.

I stare at myself, at my small breasts. And curved hips. The last time I looked at myself in the mirror … I didn’t have them. I touch my cheek, and my heart starts hammering again. Something mars the back of my hand. Black, spiderish, wrong. I take a closer look. It’s a tattoo, an oval with ten legs. A

mark

. “Conceal the mark,” I whisper. The words leave my mouth without me even meaning to speak them, as if someone else put them on my tongue. Yet I know in my gut that I must obey them.

I pull open the bathroom drawer and sigh with relief. Some of Lis’s makeup is in it. I take a tube of flesh-colored stuff and open it. Concealer. What Lis used to use to cover zits. I remember her putting it on in the mornings before she went to nursing classes at the University of Colorado, when I was twelve and wishing I were as old as my big sister. I remember everything from back then. My sister. My parents. My twin brother, Jonah. But I can’t remember why I have a tattoo on my hand, or why I

have to hide it. I can’t remember when my body stopped looking thirteen and started looking like … a

woman’s

.

Outside the bathroom door, the stairs groan—a sound I remember well. It means someone is coming upstairs. For a moment, I’m giddy with hope. Hope that my mom has come home. But then dread makes my heart speed up, because what if it isn’t my mom? I take a wide step around the spot where the floor squeaks and tiptoe to the door. Opening it a crack, I peer through.

A man is creeping up the stairs. He’s wearing a tattered pair of cutoff shorts but no shirt, and his hair is long and stringy around his face. Muscles bulge in his arms, flex on his bare chest, and swell in his long legs, and thick veins pulse under his tight, suntanned skin.

Like an animal tracking prey, he leans down and puts his nose to the carpet. The muscles in his shoulders ripple and tense, his lips pull back from his teeth, and a guttural sound rumbles in his throat. In one swift movement, he leaps to his feet and sprints down the hall toward my bedroom, his bare feet thudding on the carpet.

I have to get away, out of the house, before he finds me. I should run. Now. This very second!

Instead I freeze, press my back to the bathroom wall and hold my breath, listening. The house grows quiet, and slowly, I reach for the doorknob. My fingers touch the cool metal and ease it open a hair wider. I peer out with one eye. The floor in the hall groans, and my knees threaten to buckle. I am now trapped in the bathroom.

I grip the doorknob, slam the bathroom door, and lock it, then yank the vanity drawer open so hard it breaks away from the cabinet. I need a weapon. My hand comes down on a metal nail file, and, gripping it in my damp palm, I toss the drawer to the floor.

The bathroom door shudders and I stare at it, wondering how long before the man breaks it down. Something crashes into the door a second time. I jump as the wood splinters, and scramble backward, never taking my eyes from the door. Something hits the door a third time, shaking the entire house, and I turn to the window—my only hope of escape. Because there’s no way a nail file is going to stop the man who is beating down the door.

The window groans and fights me, the catch slipping in my sweaty grasp. As the window grates upward, the bathroom door implodes, a spray of splinters shooting against my back.

I grip the narrow window frame, just like I did as a kid, and swing my feet through. My hips follow, and then my shoulders.

A hand thrusts through the open window, attached to a scraped, straining forearm. On the back of the hand is the twin of the symbol that marks me—an oval with five lines on each side.

As I jump out the window, fingers slip over my neck, gouge into my cheek, and clamp down on my long, tangled hair. Fire lines my scalp as the skin pulls taut against my skull. I hang with my feet just above the balcony and flail, dangling by my hair. Somehow, the man’s grip slips on my hair and my shoes touch the balcony. And then, with an unexpected release on my scalp, I’m free.

I glance over my shoulder. The window frames a face with smooth skin and hollow cheeks—a boy on the brink of manhood. He peels his lips back from his teeth and growls, and I stare into his brown eyes. For a moment it is like looking into a mirror, and I almost say his name. Until I realize his eyes are wild and feral, like an animal’s. When he grips the outside of the window and swings his feet through, I scramble up onto the ledge of the balcony. And jump.

My spine contracts and my hips pop as I land on the trampoline my mother bought when I was eleven years old. The blue safety pads are long gone. I’m surprised the weathered black mat doesn’t split beneath my feet as I bounce and come down a second time, stabbing the black mat with the nail file and dragging it as far and hard as I can. I jump over the exposed springs as my brother sails through the air behind me. The mat tears noisily beneath him and he falls through it, like jumping into a shallow pond. And when he hits the ground, I hear a snap and a grunt.

I run to the fence that separates my house from the elementary school and dig my feet into the chain-link diamonds. Just like when I was a kid, racing the tardy bell, I clamber up and over the fence in a heartbeat.

As I sprint across the empty schoolyard, past the silent, rusted playground, I dare a look over my shoulder. My brother is hobbling toward the fence, his ankle hanging at an odd angle to his leg. His eyes meet mine and he holds a hand up to me, a plea to come back. A sob tears at my chest, but I look away and keep running.

A scorching sun beats down from the turquoise sky, gleaming off the distant buildings of downtown Denver. Yet no leaves grow on the skeletal trees, no flowers bloom in pots on front porches, no grass grows in dead front yards. Even the Rocky Mountains looming on the western horizon look brown and brittle. The only green in this world comes from brown-tinted pine trees—those that aren’t as dead as everything else. I am in a world of winter being burned beneath a summer sun.

I stumble through a silent neighborhood. The houses’ windows are shattered. Rusted cars sit atop flat tires in driveways. My shadow stretches long over the cracked, litter-strewn pavement. I skirt around a faded, tipped garbage can and walk faster, because deep down I can sense that this is a bad place to be when the sun sets.

My feet slow as I walk toward a telephone pole. The wires lie spaghetti-twisted on the ground below it, and tacked to the front is a piece of paper at odds with this trashed, forgotten neighborhood. The paper is daffodil yellow—not sun bleached or water warped or wind frayed. I take a closer look.