Submergence (16 page)

Authors: J. M. Ledgard

‘Very much so,’ she said.

He could not get the six he needed to put his final piece back into play. She was overtaking him. They talked on through several more games. Towards the end, she spoke about the future. But when he spoke about dead aid to Africa – how the money given out by charities was wasted – her interest wavered and she became intent on the game.

He tracked tiny movements of small people. Here today, still there tomorrow. He ate sandwiches in the canteen, chaired teleconferences, left the office before rush hour. If he was ever allowed to speak to her about the explosive part of his job, he knew he would not have the words. He would not be able to describe to her the adrenaline rush of lifting and aiming a gun. He would have left her only with a description of the noise a firearm makes when it is fired and the smell of cordite, which lingers.

There was defeatism in their conversation which allowed a greater part to Malthus, he decided, and did not take into account the advances of mankind. Among the busts around the room the only Englishmen were Isaac Newton and John Milton. He looked at Milton – impassive, unseeing – and verse crowded in. The greatest privilege of education,

he thought, was to renew and clarify your mind through the perception of others. Milton had more than played his part. Secretary of Foreign Tongues to the Republic; a freethinker who stood to the right of Oliver Cromwell, where the Levellers and Ranters stood to the left: ‘Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all other liberties.’

He thought of how in

Paradise Lost

the Archangel Raphael sat down in Paradise with Adam and Eve, not in the form of mist, but as a hungry creature who needed to eat. He spoke aloud the last lines of Book XII.

‘Say it again,’ she said. She liked the sound of his voice.

‘Some natural tears they dropp’d,’ he began, ‘but wip’d them soon; The world was all before them, where to choose Their place of rest, and Providence their guide: They hand in hand with wand’ring steps and slow, Through Eden took their solitary way.’

She had suffered from the divide in the English education system, which holds that scientists do not study Milton, and those who love Milton have no comprehension of Newton’s gravity, which brought Lucifer tumbling from heaven. But she had recovered to become a voracious reader.

They played billiards. The cues were stacked against a stone sink, where in days past billiard players would have washed their hands and faces. The emptiness of the room and the echo of their footsteps on the wooden floorboards gave the game a slightly eerie feel. Neither of them knew the rules. They made them up. She bent over the table.

‘Hell!’ she exclaimed. ‘I’m terrible. Isn’t this longer than a pool stick?’

‘Come around this side,’ he said.

He moved in behind, wrapped her up, and it began again. She was a flower about to open. He touched her arms and hands. They pulled back the cue, together they struck the white ball, it clicked the red, and for her his kiss was more than the balls striking; he touched her life, she touched his, their lives so independent and far apart from each other.

There is a dwarf antelope in east Africa called the dik-dik. They are easier to kill from a distance than to catch. In his intelligence reports he called the fight against jihadists in Somalia the dik-dik war.

But jihadists were more like weeds really, he thought. If you left them alone, they grew thick on the ground. If you cut them down, they came back stronger. So the strategy employed in the dik-dik war was no kind of strategy at all, just a periodic spraying from the air.

A bird flew into the surgery on the same day a girl was stoned to death in the square. It entered with furled wings looking to nest and lost itself, battering itself against the walls and windows. He shouted out when the bird struck him and the guards came in. They wrung the bird’s neck and beat him. It lay dead on the floor. Its claws looked like nibs dipped in ink. It was not a songbird. That is also what the cleric declared about the girl who was stoned to death in the town square: ‘She’s no nightingale.’

They dug a pit and buried her in it up to her neck. The cleric called out that he was doing Allah’s instructions. ‘I’m not going!’ the girl screamed. ‘Don’t kill me! Don’t kill me!’

They gagged her, put sacking over her head and a veil over the sacking, so the world was blacked out. They poured perfume over the sacking. Her waters span impossibly fast, she was retching from within and her hearing must have become more acute, so that immediately after prayers were ended she might have heard the men walking across the square – fifty men in all, each of them picking up rocks – and a crowd of hundreds watching, chattering, wailing. She was

fourteen years old. She might have heard the men being assembled behind a line drawn in the sand and how each of them dropped their stones at their feet and arranged them in a pile. She might have heard the crowd drawing breath as the men picked up the rocks and at a command hurled them at her head. What a mess they made of it, with their gangly arms, uncoordinated even in the levelling. So many of the rocks missed. And if the girl was never to be saved, if there was no way of going back in time, then the single service that could have been done for her would have been to replace those men with others who could throw and who would choose each stone carefully and throw straight and true, telling themselves the more accurate the throw the more merciful the sentence. That would have ended it. Instead those useless men managed only one strike in the face, smashing the girl’s front teeth. They were ordered to pick up their stones and move closer. The crowd surged in anger and there was screaming from the girl’s relatives. A young boy sprinted across the square. He was one of her cousins. They had grown up in the same house. He almost got close enough to touch her, but was shot dead just short. The men threw more stones. Some of them hit. Nurses were brought in. The girl was pulled out of the pit. She was examined and found to be still alive, so they slid her back into the hole and packed the sand and gravel around her and the stoning continued. The crowd went quiet. The girl was pulled out once more and declared dead. Her body was laid under the sun, on the world. The nurses shielded her from the men who had stoned her. They wiped the blood and fragments from her face and chest with a wet cloth and washed her for burial. They prayed over her. She was buried under a fig tree in a street near where the boys played table football. Her feet were pointed towards the ocean, her head to the square. She had been sentenced for adultery, after reporting to the religious authorities that she had been gang-raped.

A biblical scene – no, a Koranic scene – the clerics, the men standing behind the piles of stones, the exclamations, the strange trees casting

their shapes, the dust itself, the stones flying and missing. It was ancient, also new. The sermon that followed was played over loudspeakers in the town. He had pushed the bird away and listened. Barbed wire was drawn across the square, the gun on one of the Land Cruisers was directed at the crowd. There was a camera recording it for a website. They downloaded the video onto a phone and forced him to watch. No matter how many times it was sped up or slowed down, no matter the cutaway or close-ups, there was no way to correct it: it was an injustice that could never be corrected. If you paused it, he thought, the stones would not stop in the air. If you muted it, the sound would continue.

When the feeding of the people in the port was over, he walked across the town square with the fighters. The moon was out. The square was ashen. The pit was still there. One of the fighters pointed it out. It was filled in with darker earth. A pock.

He fainted one afternoon in the surgery, in the white, and saw Yusuf al-Afghani standing in a wadi in the Somali desert. Clouds passed over. Yusuf’s arms were sunk to his elbows in a jar of spermaceti. It shifted, and Yusuf was on the deck of a ship, a sea captain, a brigand, the ship standing still, the sails limp, it was before a tropical storm, all the air sucked out. Then the ship was gone, sunk, and Yusuf stood under a palm tree and he saw the smooth black hands entering into spermaceti. They must be there in the white jar, they could not disappear, but how was it possible to know? What was Yusuf doing? Was he going to anoint himself with a mark of spermaceti oil on his forehead,

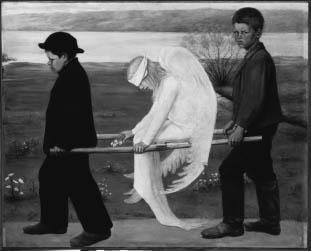

a blessing at a coronation, or was he going to bring handfuls of the white stuff to his mouth and eat it softly like calf’s brain? He watched and was made cognisant of another image, of the Finnish painter Hugo Simberg’s wounded angel, carried by two boys, a painting he had seen as a young man in a Helsinki summer long ago, and which forever changed the way he saw the world.

It was a melting in him, visually. There was John More swallowed by a sperm whale off the Patagonian coast and Yusuf with his forearms sunk in a jar of spermaceti, and there was Simberg’s angel, and he could not see the connection, except in the whiteness of the windows in the surgery, of the jar, of John More cut by flensers from the whale’s belly, the whiteness of the angel’s bandage, and the wound beneath; and there was the face of the boy in the Simberg painting, who stared at him as he passed by, a face that could have been his own.