Sudden Sea (16 page)

Mee was one of the few who believed that the thunder of the sea was a warning as baleful as any the Weather Bureau might issue. By late afternoon, he and Helen had decided to move inland, where the children would be safer, and they offered a ride to their neighbors, the Breckenridges. Four Mees, their maid, three Breckenridges, and two dogs crammed into the car and set out along the shore road through the driving rain. The ocean was slithering across the roadway, but the Mees had only one mile to drive to reach the mainland.

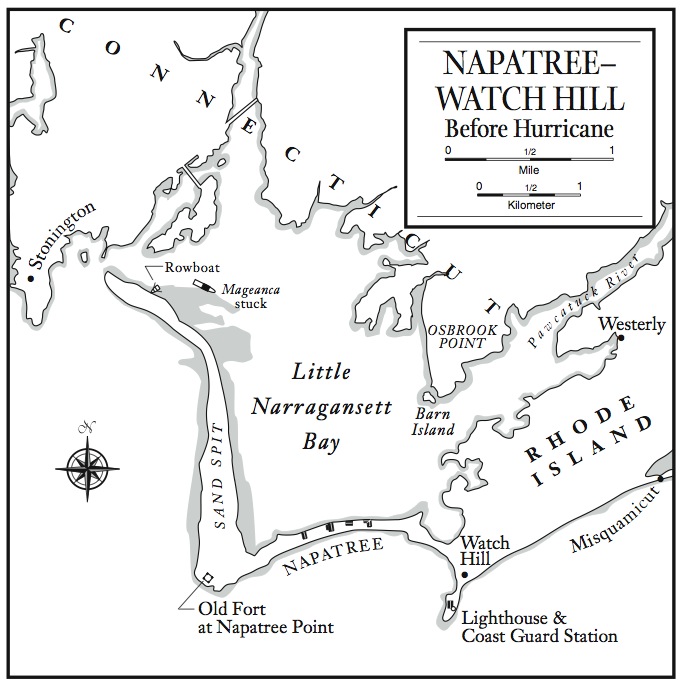

Charlestown Beach is one of the small oceanfront communities along Rhode Island’s South County coast. When the sea came ashore, there was no high ground to flee to. Like Westhampton Beach and Napatree, each town had a single road that ran parallel to the ocean. Within moments it was swamped. Across South County and up through Narragansett Bay, a storm surge that one incredulous survivor described as “mountains high” turned these ocean communities into deserts.

Even on the mainland, those who could look across the tidal ponds had no idea what was happening out on the beaches. Visibility was poor and telephones and electricity went out as early as 2:30

P.M.

Norman Behneke lived directly across the salt pond from Charlestown Beach. Even when cars were flooding, he said, “it was hard to believe that the dark creeping thing coming up the road was water. Suddenly, as you looked again, it seemed to boil, and out of the haze of the spray there loomed up something which stunned you.” Bungalows from Charlestown Beach were riding a racing wave across the pond. Bodies, living and dead, piled up on the shore, battered and entangled by the wreckage of their lives.

A Charlestown Beach survivor described the sight: “Out of nowhere, there came one walloping big wave that seemed to tower above even the highest building, and we were washed for miles, it seemed, before the water subsided and let us down. It took only a few minutes to sweep the beach clean.” On the morning of the twenty-first, there were seven hundred houses along this stretch. By nightfall, there was none.

Just down the road at Misquamicut, E. L. Reynolds, assistant fire chief, remembered exhilaration turning to terror: “People on the beach were laughing and joking, trying to put up shutters and fastening windows to keep curtains from getting wet. They thought it was lots of fun. Then suddenly their homes were under twenty or thirty feet of water. Some of the houses just blew up like feathers. I saw one leap seventy-five feet into the air and collapse before it hit the water.”

The women of the Mothers Club of Christ Church, Westerly, were having a picnic of carrot and egg salad sandwiches at a Misquamicut beach bungalow. They had postponed their outing twice because of rain, and when the sun shone Wednesday morning, they seized the day. After a Communion service at the church, they went out to Misquamicut for the picnic. Zalee Livingston, a seamstress, brought her four-year-old grandson, but the thundering breakers frightened him. Rector John Tobin, who was returning to the church to conduct a funeral service, took the boy with him. By then, the women were halfway through lunch, their sandwiches more sand than salad. The wind was so strong, they moved their picnic to a sturdier house up the road. In a matter of minutes, swirling seas surrounded it.

In the midst of the storm, a worried husband drove his pickup truck to Christ Church, hoping for news of the women. At dusk, as the winds began subsiding, he and Jack Tobin, the rector’s twenty-five-year-old son, rode out to Misquamicut. They drove through the Misquamicut Golf Club to the edge of the fairway. It bordered the saltwater pond, directly across from the picnic spot. “The fairway was covered with chunks of houses,” Tobin remembers, “not splinters — big pieces. The man got out of the truck and stumbled over a woman’s body. It was his wife. He started giving her artificial respiration.” Tobin was studying medicine at Yale, but you didn’t have to be a doctor, he said, to know the woman was dead. “Bodies that had washed across the pond from Misquamicut were scattered all over the green.” Today, the names of the Mothers of Christ Church are inscribed on a stone monument by the church. It is the only hurricane memorial in the state.

Four hundred died in Rhode Island, 175 along the South County shore. Some oceanfront towns were reduced to mounds of wreckage ten and twelve feet high. Others were wiped away as cleanly as if swept by a broom. There was nothing left except a few telephone poles, a couple of cement steps, a tub or toilet half submerged in the sand.

Timothy Mee drove three-quarters of a mile down the beach road. Another quarter mile and he would reach the mainland. He was driving slowly because the ocean was slapping against the side of the car. The engine flooded. Mee was pumping the gas pedal, holding the key in the ignition, trying to get started again, when a gust picked up the car with everyone in it. Helen and Agnes clutched the children, covering them with their bodies. They were too stunned to scream. What was happening seemed impossible. Their sturdy family car, weighed down by six adults, two children, and two dogs, was tumbling down the road, blowing away like a lost hat or an autumn leaf. Children, adults, and animals were bumping together, banging against the doors one second and the roof the next. The car revolved three times, bounced to a halt, and skidded on its side.

Mee and Breckenridge managed to wrench a door open and pull the women and children from the overturned car. They huddled behind it for protection from the wind. Against such a ferocious force of nature they were as helpless as motes of dust, yet they had to strike out. The water was up to their waists and rising rapidly. They formed a chain, holding hands, when suddenly and without a bit of warning, a terrifying sight appeared from the ocean side. What looked like a polluted lake was bearing down on them. The water was a soiled gray, and towering over it another ten feet was a crest of murky froth — and the whole filthy body of water was rushing toward them. Helen Mee was holding the baby; Agnes Dolan had Timmy. Mee wrapped his arms around them all, hugging them with every ounce of strength he possessed. The lake struck them like a bolt of lightning and tore Mee’s family from his grasp.

In Watch Hill, Bob Loomis, a summertime policeman, was off duty and doing some yard work that Wednesday afternoon. He had just finished cutting his lawn when the day took a strange turn: “All of a sudden everything became very, very quiet. Even the birds seemed to stop singing. The sky began to take on an unusual look. The clouds were very low and moving at an unusual rate of speed.” He started to rake up the clippings, but the wind was too quick. It swooped in from the southeast, scattering the piles faster than he could rake.

Loomis lived just up the road from the Watch Hill Lighthouse. About three o’clock, he walked over to check on the forecast. The wind in the Coast Guard tower registered about sixty-five miles per hour, and the barometer was dropping. Small-craft warnings were flying, but the Coast Guard had not received any alert that a hurricane was bearing down on the Northeast.

The first and only warning of a serious storm would come into the Watch Hill station just after Loomis left. By then, water was snaking over the low end of the road. In the few minutes it took him to walk into town, the Great New England Hurricane reached Watch Hill.

About the same time that Officer Loomis left the Coast Guard station, Captain Mahlon Adams was bringing the yacht

Heilu

into the harbor. He was securing it at the Watch Hill Yacht Club with his heaviest hawser when he saw a wave unlike any he had ever seen. It looked “like a roll of cotton.” It towered thirty feet, and it was advancing on Fort Road. With a resounding roar, the yacht club split in two and a piano flew out “like a big black bird.” The

Heilu

was lifted over the pier and landed in the center of town beside the fire station.

Loomis saw the yacht club go, too: “Lo and behold, it was lifted right up in the air and crashed out into the middle of the bay. As we looked over toward the pavilion, we could see the water coming over the road and rushing into the bay. At the same time, the tide in the bay began to rise so fast we had to jump onto the wall to keep from being submerged.” Within minutes “four or five houses came scudding across the bay and we realized that Fort Road was doomed.”

Napatree extended west from the yacht club. When the first wave advanced up the beach, it hurdled the old fort, smashed the sea-wall, and climbed up the front steps of the bigshingled houses. Moments later a second giant wave piled on top of it. Foaming like a mad Cerberus, it broke over the gracious summer houses that lined Fort Road. There were forty-two people in the Napatree cottages when the Atlantic came ashore.

Jane Grey Stevenson and her sister, Mary, lived at Stevecot, the first house on Fort Road, with their maid of many years, Elliefair Price. The Stevenson sisters were as much a part of village life as the Watch Hill merry-go-round. For as long as anyone could remember, they had kept a gift shop in the old schoolhouse. Each morning before opening Miss Stevenson’s Little Shop, Jane Grey swam in the ocean. She was a wisp of a woman, with a soft voice and a timid manner, who had always seemed to be in her ebullient sister’s shadow. But now that Mary Stevenson had diabetes and did not get into the store much, Jane Grey kept the place going on her own.

On the twenty-first she closed early; she wanted to get back to Mary and Elliefair before the storm got any nastier. About four o’clock, just as the Stevensons were finishing their tea, the first wave broke. It swirled around the cottage and slunk up through the floorboards. Jane Grey packed an overnight bag, and the three women went into the kitchen to wait on the bay side for the Coast Guard boat. They were sure it would pick them up. Mary and Elliefair sat on the kitchen table to keep dry. Jane Grey, knee-deep in water, stood watch at the back door. They assured one another that the boat would be along any moment. They did not feel the slightest bit of fear, because whenever there was high water on Fort Road, the guardsmen always came with a cutter.

From the tower at the Watch Hill station, the Coast Guard saw the first cottages on Fort Road go. It was just a glimpse before the picture dissolved. Sea, sky, and land merged into a single element. Rain and spindrift became so thick, visibility was reduced to about one hundred feet. The barometer was nose-diving, a point every five minutes, and the tower was swaying under winds clocked at 120–150 miles per hour.

The Atlantic pounded the lighthouse point, streaming over it, beating around it — taking out the garden, seawall, road, everything except the glacial rock beneath it. A salty river rushed between the station and the town of Watch Hill, and thirty feet of gray-green water cut a breach between the Coast Guard station and the adjacent lighthouse, making each an island. Officers rigged guidelines from one to the other, but they could not reach their cutters. No rescue boats would be going out to Napatree.

When Bob Loomis reached the center of Watch Hill, a hail of debris was skipping down Bay Street, zipping by the row of smart shops. Picked up by the swirling wind, traffic signs and roof shingles took off like rogue missiles. Ducking and dodging the flying objects, shopkeepers ran from their stores, not even taking time to lock up. A Watch Hill Improvement Society rubbish can whizzed by Loomis’s head, nearly taking an ear with it. He was just passing the fire station when the second wave broke: “The water rushed into the firehouse, hit the back wall, and on the rebound washed all three of the fire trucks right out through the closed doors.”

In a matter of minutes, the storm was tearing up Watch Hill and washing Napatree into the sea. Loomis figured that if it continued at the same intensity, the loss of life and property would be worse than anything the area had ever experienced. With no car and no means of communicating with the rest of the world, he set out on foot for Westerly, six miles away, to get emergency relief.

Far out on the Napatree beach, the lovebirds Lillian Tetlow and Jack Kinney had gone as far as they could. They had passed the houses and the fort and reached the farthest point when the weather turned. The change was quick and dramatic, as if an awning had been lowered over the day. The sky turned gunmetal gray. The ocean changed to black marble. The sandpipers had vanished — Lillian and Jack did not notice when or where they went. Suddenly afraid, the sweethearts started back. On the beach, the wind now in their faces, the waves breaking higher and higher on the sand, it could have been a different day. The perfect beach morning was gone without a trace. Even the colors seemed to wash away.

When they turned toward Watch Hill, they felt as if they had stepped into a grainy black-and-white movie. They began to run, but the gusting wind pushed them back. They bent into it, pressed against it. Lillian clung to Jack’s arm, and he pulled her along. Rain like nails pounded them. Foam flew, and rain, and spindrift. They could not see where sea and sky met, or hear each other over the wind. It whined as it worked, whipping sand, spray, and rain into a murky batter, adding broken shells and splintered driftwood, and hurling it in their faces. They sank into the sand, each step harder than the one before. Lillian began crying, and they were both shaking with cold and wet and fear.