Sunset at Blandings (23 page)

Read Sunset at Blandings Online

Authors: P.G. Wodehouse

There

were deer in the park in the two earliest Blandings books. But we think that

the problems of fencing, ha-has, winter feeding and (whisper it) poaching

decided Lord Emsworth to let the herd (Japanese and Sika) run down, and to give

the remainder to a not-too-neighbourly landowner he met at one of those Loyal

Sons of Shropshire dinners. It was quite a business rounding the deer up and

carting them. Shropshire has wild deer these days the way East Anglia has

coypus, and direct descendants of escapees from the Blandings herds are

sometimes seen in the West and East Woods and in the copse north of the stables

(1 4N) . Nobody molests them, though McAllister would like to. He curses them

when they get into his gardens, and the foresters don’t like the way they eat

the bark off young trees.

In

Heavy

Weather,

at the end of Chapter 6, we read: ‘Sir Gregory Parsloe hurried

from the room, baying on the scent like one of his own hounds’. Can this mean

anything but that Sir Gregory is the local Master of Foxhounds? Whether or no,

Lord Emsworth has the living of Much Matchingham in his gift (end of ‘Company

for Gertrude’ in

Blandings Castle).

Is it conceivable that Matchingham

Hall is on the Blandings estate and that the hated Sir Gregory, M.F.H., is one

of Lord Emsworth’s tenants, but claiming the right to hunt his landlord’s land?

There is mercifully little about blood sports in the Blandings books, though we

know Gally kept his gun at the castle

(Summer Lightning),

Lord Emsworth

has a pistol with ammunition

(Something Fresh)

and Colonel Wedge comes

to the castle with his service revolver ready for use

(Full Moon)

. Add

to these young George and his airgun, and it still doesn’t make a bloodthirsty

household.

You can

see horses in that paddock (7U) . I doubt if they are hunters. There is better

evidence for them than for the supernumerary pigs. Hugo Carmody rode, in his

secretarial days at the castle

(Summer Lightning).

You see cows in a far

field (16, 17K). Those provide milk for the castle and would sometimes, when

their grazing is changed, use the cow-byre (10V) where, on the afternoon of the

Bank Holiday binge, Lord Emsworth found his little slum-child girl friend. And

you can see (5P) the house in Blandings Parva, with the garden at the front,

where that girl had quelled the aggressive dog, and brother Ern had bitten

Constance in the leg. Just where the girl was when she copped McAllister with a

stone is not utterly clear.

Where

are the boundaries of Blandings set? Of what noble species are those huge ducks

on the Blandings Parva pond (1 Q)? Under which of the gravestones in Blandings

Parva churchyard (2N) are Lord Emsworth’s parents, and his late wife for that

matter, buried? We assume that it is to Blandings Parva that they went to

church (the only such occasion specified) in

Something Fresh,

though

then they had staying in the house party one bishop and several of the minor

clergy. Who is living at Sunnybrae cottage (6G) now? Galahad put one of his

Pelican Club friends into it, but the man got scared of the country noises and

went back to London. Into which window of the castle does Jeff climb in this

book, to meet the startled Claude Duff? Where is the little dell near the small

spinney in which Baxter’s parked caravan invited pig-stealers plus pig

(Summer

Lightning)?

Who has left that gate open (18L)? And are those (2G) boys from

Shrews-bury sculling for home?

These

are good questions. Where we have tried to answer others, we claim no

originality of interpretations. What we do claim is that we have done a good

deal of homework. Whether we have got the answers which would have pleased

Teacher, we can never know, since he is no longer at his desk.

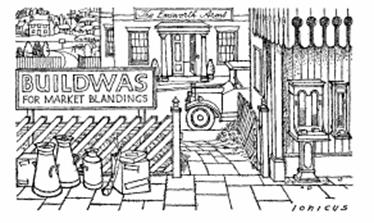

THE TRAINS

BETWEEN

PADDINGTON

AND MARKET BLANDINGS

FROM my earliest readings

in Wodehouse I had had a suspicious eye on the trains that connected Paddington

and Market Blandings. I thought the author was inventing train-times as the

mood took him, hardly looking back to earlier chapters of a book, let alone to

earlier books. I doubted whether any of his train-times would square with the

Bradshaws

or

ABCs

of the publication dates of the books in which they

occurred.

Not

that I would hold it against him if that’s the way he was doing it. But I

wanted to see, and particularly to see if train-times provided any evidence of

where in Shropshire Blandings Castle might be. There are, or there were in the

days of the 1953

Encyclopaedia Britannica

(Sarsaparilla to Sorcery),

1,346.6 square miles of Shropshire. Perhaps the railway evidence in the books

might help us to put the mythical Blandings on a real map.

No

scholar, as far as I know, had collected all the railway references and laid

them out for inspection. So, since this last chronicle of Blandings adds one

last train to the time-table, I have brought them all together. It was not

difficult, only laborious. But interpreting the references was beyond me. I

could see no pattern, if any existed, in the times and speeds. I could see one

obvious anomaly. In

Leave it to Psmith,

Psmith says it’s roughly a

four-hour journey either way. But, elsewhere in the same book, the narrative

says that the 1250 from Paddington arrived at Market Blandings ‘about 3 o’clock’

(1500). My guess is now that that ‘3’ was originally a misprint for ‘5’ and has

persisted uncorrected through half a century of editions. Otherwise we have a

train, not even called an express, doing the four-hour journey in 2 hours 10 minutes.

Besides,

as recently as 1969, when Wodehouse was eighty-seven, he said to Peter Lewis of

the

Daily Mail,

at the end of an interview at his Long Island home, ‘By

the way, about how long does it take now from Paddington to Shropshire? About

four hours? Good, I always made it about four hours.

To

avoid the bother of a.m. and p.m., I have translated all train times to the

Continental clock. And I have added the publication dates of the books from

which I combed my references. It looked professional and it might provide

clues. And I have included the ‘stops at —’ and ‘first stop —’ details as given

in the texts. We get them only four times, always on trains from Paddington.

And in three cases out of the four they have a purpose.

I can

see no point in Freddie Threepwood adding ‘first stop Swindon’ in relating to

Bill Lister that the girl of his (Bill’s) heart has been sent to Blandings on

the 1242

(Full Moon)

. But with the 1615 express, the addition of ‘first

stop Swindon’ in

Something Fresh

is a plant. Ashe Marson and Joan

Valentine are travelling to Blandings together, he to be valet to an American

millionaire, she to be lady’s maid to the millionaire’s daughter. There is a

little job of retrieving for the millionaire the priceless scarab that Lord

Emsworth has forgetfully pocketed and then assumed to be a most generous gift.

And the millionaire will pay handsomely for it to be returned for him. Since

both Ashe and Joan are out for the reward, Joan wouldn’t mind if Ashe were

eliminated from competing. So, between Paddington and ‘first stop Swindon’, she

tells him grisly tales of the hardships and snubs that lesser servants have to

suffer below stairs. Having frightened him, she says ‘Wouldn’t you now like to

get off at Swindon and go home?’

And

when, in ‘Pig Hoo-o-o-o-ey!’ in

Blandings Castle,

the 1400, ‘best train

of the day’, stops at Swindon, it is with a jolt just sufficient to wake Lord

Emsworth up and make him realize that he has already forgotten the master

hog-call that might make his beloved Empress start eating again.

The

third purposeful stop is the ‘first stop Oxford’ for the 1445 express in

Uncle

Fred in the Springtime.

Lord Ickenham, king of impostors, is gaily

travelling towards Blandings Castle in the guise of Sir Roderick Glossop, the

loony-doctor. With him is Polly Pott, in the guise of his secretary. And his

quaking nephew Pongo is with them in the guise of Sir Roderick’s nephew. So

far, so snug in a first-class compartment. But then the Efficient Baxter is

seen getting into the train at Paddington, and he starts by being suspicious of

the whole party. But worse, much worse, is to come just as the train is pulling

out. The real Sir Roderick himself gets on. This really is a facer for Uncle

Fred. Lord Emsworth had told him that, pursuant to his sister’s commands (it

was she who was worried about the Duke of Dunstable being potty), he had gone

to London to make the acquaintance of the great alienist and persuade him to

come to Blandings to vet the Duke. But, Lord Emsworth said, he had discovered

that Sir Roderick was the grown-up version of the horrid little boy they had

called ‘Pimples’ at school. Sir Roderick, thus addressed by Lord Emsworth

today, had refused the invitation to Blandings. That then enabled Lord Ickenham

to set up his three aliases and his triple storming of the castle: on Lord

Emsworth’s behalf, and to help a couple of young couples find happiness. ‘Help

is what I like to be of,’ says Lord Ickenham.

And

here was Sir Roderick Glossop, in person, getting on to the train at

Paddington, having changed his mind. Lord Ickenham needed that stop at Oxford

badly. It gave him time to talk Sir Roderick into believing that the patient he

had been so hurriedly sent for to inspect had turned the corner and needed no

immediate attention: so Sir Roderick could go back to his busy practice,

stepping off at Oxford and catching whoknowswhat train home to London.

Finally,

if train times helped to give Market Blandings a position on the map of

Shropshire, we might decide which way the Vale of Blandings went. We put the

castle at the end. For how many miles does the Vale stretch? Is Market

Blandings short of, or beyond Shrews-bury, its nearest reasonable-sized shopping

town? Do you turn left or right for Shrewsbury when you come out of the castle

drive on to the main road?

I

decided to ask the help of a friend of mine who had been a

Bradshaw

expert

at his (and my) preparatory school, long before he joined British Railways as a

career. This was the evidence I supplied:

Trains from Paddington to Market

Blandings

0830

express

(Sunset at Blandings

1977).

The train that arrives at 1610

(Service with a Smile

1961).

1118

(A Pelican at Blandings

1969).

1145

(Service with a Smile

1961).

1242

‘first stop Swindon’ arrives ‘shortly

before 1700

(Full Moon

1947).

1250

arrives about 1500—i.e. about 2 hours 10

minutes ? this a misprint

(Leave it to Psmith

1923).

1400

‘best train of the day’. Stops at

Swindon

(Blandings Castle

1935).

1423

(A Pelican at Blandings

1969).

1445 express. First stop

Oxford

(Uncle

Fred in the Spring time

1939).

1515

(Blandings Castle

1935).

1615 express. Stops at

Swindon

(Something

Fresh

1915). An express that arrives c. 2105. Restaurant car

(Leave it

to Psmith

1923 and

Uncle Fred in the Spring time

1939).

1705 ‘there is nothing between

the 1400 and

this’

(Blandings Castle

1935).

Trains from Market Blandings to

Paddington

0820

‘arrives about noon’

(Uncle Fred in

the Springtime

1939).

0825

(Uncle Fred in the Springtime

1939).

0850 arrives about

midday

(Leave it to

Psmith

1923).

1035

(Service with a Smile

1961).

1050

(Something Fresh

1915).

1115

(Hot Water

1932).

1240 arrives shortly before 1700

(Full

Moon

1947).

1400

(Blandings Castle

1935

and

Uncle Fred in the Springtime

1939).