Swords From the East (72 page)

Read Swords From the East Online

Authors: Harold Lamb

Tags: #Historical Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Suspense, #Adventure Fiction, #Historical, #Short Stories, #Adventure Stories

I then entered Agra and took up my residence at Sultan Ibrahim's palace.

Chapter V

Dominion

At once I began to examine and distribute the treasure. I gave Humayun seventy lakhs from it, and a palace. To some of my lords I gave eight lakhs, to others less-on the allies, the Afghans, Hazaras, Arabs, and Baluchis, that were in the army I bestowed gifts. Every merchant, every man of letters, every person who had come with me into Hindustan, carried off presents, rejoicing in his good fortune.

All my relations and friends in my homeland had gifts sent to them, great and small, and to every person in Kabul I gave one silver coin as a gift.

When I came to Agra it was the hot season. Many of the inhabitants fled from terror, taking their grain with them; others hid it away, so that we could not find enough provender for ourselves or the horses. The peasantry of the countryside avoided my men, and the townspeople were hostile at first.

The villages had taken to thieving and robbery. The roads became impassable. It happened that the heat in this season was uncommon, and many men dropped down as if they had been struck by the simun wind, and died where they fell.

Although the country of Hindustan is populous and rich, it has few pleasures. The people have no good-fellowship, as in the northern hills-no kindness, no good horses, or meats or fruits such as our grapes or muskmelons. They have no cold water or good bread in the bazaars, no baths-not even a candle. Instead of a candle you have a gang of dirty fellows to follow you about with a kind of smoking lamp made of a wick in an iron vessel into which oil is poured.

The lower classes go about naked. They tie on a thing like a clout as a cover to their nakedness. In Hindustan even the time is altered, as they divide a day into sixty parts instead of twenty-four. They measure each part by the dripping of water from a hole in a cup, and when the cup is filled they beat upon a brass basin in such a manner that a man awakened from sleep in the night by the beating of the basin does not know what hour it is. I directed that they should likewise beat the number of the night watch.

Most of the natives of the country are pagans, who are called Hindus. The greater part of them believe in the doctrine of transmigration, and the son often works at the trade of the father. For every kind of work there is a certain guild, and the multitudes of craftsmen is a great conve nience. In Agra alone I employed on a new palace six hundred and eighty persons each day.

Their buildings are purposeless and ugly; they lack pools or canals in the gardens, and during the rainy season the dwellings are far from staunch. At this time heavy rain falls ten or twenty times in a day; bows and their strings become quite useless; coats of mail rust and books mold. It is pleasant enough between rains, but in the dry season the north wind always blows and there is an excessive amount of dust in the air. It grows warm during the signs of the Bull and the Twins, but not so warm as to be unbearable-not nearly the heat of the northern deserts.

The heat had its effect on my men. Not a few of the Begs began to lose heart and complain of their suffering in Hindustan. Some made preparations to go back to the hills.

No one had behaved better or spoken more gallantly than Kwajah Kilan from the time we left Kabul; but a few days after the taking of Agra he was the most determined to go back.

As soon as I heard this murmuring among my men, I summoned all Iny Begs to a council, and spoke to them: "After great hardships and exposure to danger we have routed our enemy and conquered the kingdoms we now hold. Empire cannot be held without gathering the materials of war. To go back now to Kabul would be to retreat. What invisible foe compels us to give up the achievement of our lives?

"Let no one who calls himself my friend ever speak of retreat. But if there is any among you who cannot bring himself to stay, let him depart."

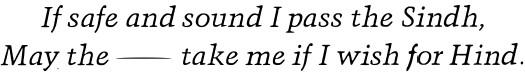

Nevertheless Kwajah Kilan was resolved to go, and it was arranged that he should have charge of the treasure I was sending to Kabul. He was heartily sick of Hindustan and at the time of going, wrote on the walls of a house in Delhi:

As some two or three thousand Afghan bowmen had come in to join me, and several of Sultan Ibrahim's officers had rendered allegiance to me, we had a great feast a few days after the end of Ramazan when the new moon first appeared. It was in the great hall of stone pillars under the dome of Sultan Ibrahim's dwelling palace. At this time I presented Humayun with a shawl of cloth of gold, a sword, and a Kiptchak horse with a gold-adorned saddle. To Chin Timur Sultan and to Mahdi Kwajah I gave a similar shawl, with a sword and dagger-to the other lords and officers I gave according to their rank and merits.

Yet the feast lacked something of the high spirits of our northern banquets. Rain fell heavily, and those who were seated outside the hall were thoroughly drenched.

I had made up my mind to have running water in my new gardens of Agra, by building waterwheels at the river-and to lay out the gardens in better fashion. But the Jumna and the countryside was so ugly and detestable that I was disgusted. I was obliged to give up irrigating the countryside and to make the best of the palace gardens as they were.

First we sank a deep well and constructed baths at its edge, far below the surface of the ground. In every garden I sowed roses and narcissus and erected buildings out of white and red stone.

We were troubled by three things in Hindustan-heat, strong winds, and the dust in the air. The baths gave us relief from all three. Some of my veteran officers began to follow my example with their new estates-building regularly and not haphazard after the Hindustan fashion, which is merely to set up shelters of mud, branches, and wood, and palaces without plan or beauty.

My companions made their gardens and waterwheels after the manner of Lahore, and the men of Hind, who had never seen so much elegance, called our new countryside Kabul.

I had asked Ustad Ali, the Master of Cannon, to cast a large piece for the purpose of battering some of the citadels that had not submitted. After working diligently at the forges he sent word to me that everything was ready. Ustad Ali was devoted to his cannon. We went out to see him cast his gun.

Around the place where it was to be cast were eight forges with all needed tools in readiness. From each forge the men had made a channel that ran down to the mold in which the gun was to be cast.

On my arrival they opened the holes of all the different forges. The metal flowed down the channels, a glowing liquid, and entered the mold. After some time the flowing of the melted metal from the forges ceased, one after another, before the mold was full.

There had been some oversight in the forges or the supply of metal. Ustad Ali was in terrible distress; he was like to throw himself into the glowing metal that was in the mold. To cheer him up I gave him a dress of honor and contrived to lessen his shame.

Two days after, when the mold was cooled, they opened it. Ustad Ali, in great delight, sent to tell me that the shot chamber of the great gun was without a flaw, and that they could easily cast the powder chamber. Having raised the finished chamber, he set men to polish it, while he began anew at the forges to fashion the powder chamber.

Three months later the great gun was finished-the powder chamber having been perfectly cast-and Ustad Ali made ready to fire it. We went to see how far it would throw the ball. About afternoon prayers the piece was discharged and carried one thousand six hundred paces. I bestowed on Ustad Ali a dagger, a complete dress, and a Kiptchak horse, to honor him.

When winter came on again, a strange thing happened, in this wise-the mother of Ibrahim, an ill-fated lady, had heard that I had eaten some things prepared by natives of Hindustan. A few of Ibrahim's cooks had been kept at the palace to prepare dishes of Hindustan for me. The lady sent a girl slave to Ahmed the taster with a bit of poison wrapped up in paper, and another slave to watch the first. Ahmed gave it to one of the Hindustani cooks with the promise of four houses if he would throw it into my food.

Fortunately the poison was not thrown into the pot, because the Hindustani cooks were closely watched at the fires, but he tossed it into the tray that was to be carried in. My graceless tasters were not watching, and he was able to cast it upon some thin slices of bread. In his haste, he spilt about half the poison. Then he put some fried meat in butter on the bread.

On Friday, when afternoon prayers were over, the dinner was served. I was not aware of any unpleasant flavor, but when I had eaten a little smoke-dried meat I felt nausea. When I knew that I could not check the nausea I left the table. My heart rose in me and I vomited.

I had never before done that, even after drinking heavily, and a vague suspicion crossed my mind. I ordered the cooks to be bound, and the meat to be given to a dog which was to be shut up immediately after. Next morning about the first watch the dog became sick, and his belly swelled. He would not get up even when he was poked with a stick. About noon he got up and recovered.

Two young men had also eaten of the meat, and one of them fell very sick. I ordered the cooks to be examined and at last all the details came to light.

On the next court day I directed all the grandees and the ministers to attend the diwan (council). The two guilty men and the two women were brought in and repeated all the plot. The taster was ordered to be cut into pieces. I commanded the cook to be flayed alive. One of the women was ordered to be trampled to death by an elephant, the other to be shot with a matchlock.

The lady*

was deprived of her possessions and slaves and kept under guard. Someday her guilt will bring its retribution.

I had scoured myself inside with milk and the juice of the makhtum flower, and, thanks be to God, the illness had passed off. I did not realize until now that life was so sweet a thing. Whoever has ventured near the gates of death, knows the joy of life.

Chapter VI

The Land of Kings

At this time messengers began to come, close upon each other, from Mahdi Kwajah to relate that Rana Sanga and the Rajputst

were on the march.

Of all the pagan princes Rana Sanga was the most powerful. He had won his conquests by his own valor and his sword. His original principality was Chitore. During the last wars he had seized such places as Rantambor and Marwar. He was the chief of all the Rajputs.

When I entered Hindustan, Rana Sanga, the pagan, had agreed with me that if I would march against Delhi he would advance from the other side against Agra. Yet when I defeated Ibrahim and took Delhi and Agra, the pagan did not move out of his forts.

At the edge of his country, yet near to Agra, was the city of Biana. The great cannon that Ustad Ali had fashioned was to batter down the walls of Biana. But when Rana Sanga marched with his army against Biana, the Khan of that place saw no remedy but to deliver up the fort to my troops.

I had sent Mahdi Kwajah to take command at Biana. In his messages he urged that a light force be hurried to his city in advance of my army. I sent the advance force, but it never reached the fort. The garrison of Biana had gone out toward the pagans with too little caution and had been routed.

When the affair began, Kittah Beg came galloping up without his armor and joined in. He had dismounted a pagan and was about to grasp him when the Hindu snatched a sword from a servant of the Beg and struck my officer in the shoulder, wounding him severely. Long after, Kittah Beg recovered, but was never entirely well. Whether from fear or to excuse themselves, all my people who came back from Biana bestowed unstinted praise on the courage and hardihood of the pagan army.

On a Monday in midwinter I began my march to the holy war against the heathen.

Of all the places before me, the water was best in the plains of Sikri, and thither I marched, in battle order, sending a galloper to Mahdi Kwajah with instructions to join me with the remnant of the Biana garrison. At the same time I sent out riders to watch the movements of the pagans.

The Hindus were marching toward us, and as soon as they had news of my advance detachment, which had pushed on incautiously ten or twelve miles from Sikri, four or five thousand of them fell upon my men, who stood their ground in spite of being outnumbered.

The moment I heard of this I detached a strong covering force under a veteran officer to cover their retreat. My men of the advance were badly cut up, lost a standard, and had to flee for two miles before they reached the covering division. Many good men and officers were slain.

From all quarters word began to come that the enemy were close at hand. We buckled on our armor, arrayed our horses in their mail, mounted, and rode out. After marching a mile or so we found that the enemy forces had drawn back.

As there was a large tank on our left, I camped in this place. We fortified guns and connected them with chains. Mustapha the Osmanli was very clever in arranging the cannon in the Turkish manner, but as Ustad Ali was jealous of him, I stationed him on the right with Humayun, keeping Ustad Ali with me. Where we had no guns the spade-men dug ditches.