Taking Liberties: The War on Terror and the Erosion of American Democracy (24 page)

Read Taking Liberties: The War on Terror and the Erosion of American Democracy Online

Authors: Susan N. Herman

Tags: #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Law, #Civil Rights, #Intellectual Property, #General, #Political Science, #Terrorism

Although the Supreme Court declared in these cases that “society” was not prepared to recognize any legitimate expectation of privacy in such instances, American society seemed to disagree. Congress reacted to

Miller

by enacting the Right to Financial Privacy Act of 1978

36

in order to protect customers of financial institutions from “unwarranted intrusion into their records while at the same time permitting legitimate law

enforcement activity.”

37

The Act prevented fishing expeditions in financial records by requiring the kinds of protection the Fourth Amendment would have, had it been deemed applicable, like notice and judicial involvement. This was the law until the Patriot Act crafted exceptions so that financial institutions could collaborate in filling government databanks. And the decision in

Smith

led Congress to enact the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, requiring agents to obtain a court order before seeking an individual’s telephone log from a telephone company.

38

This statutory privacy protection too was later diluted by the Patriot Act, as

chapter 9

will recount, leaving telecommunications information again exposed to government collection without any court order at all.

Scholars have been critical of the

Miller/Smith

assumption of risk theory.

39

And there are cogent arguments that highly intrusive post-9/11 surveillance mechanisms are indeed unconstitutional despite

Miller

and

Smith

, especially where the highly revealing records of Internet service providers are involved.

40

The third-party doctrine made more sense in the pre-Internet world where the locus of most private activity was in the home. The Supreme Court has been very protective of the privacy of activities in the home, even if those activities are illegal—like growing marijuana,

41

or watching obscene videos.

42

But especially since the advent of “cloud computing,” there is little distinction between what an individual does at home and the information that individual shares with an Internet service provider. While the framers of the Constitution stored their constitutionally protected “papers and effects” at home, Miller and Smith did not possess their own records; they had to share certain types of information in order to use a bank or a telephone. Many Internet users, because of cloud computing, share an infinitely broader variety of information with their Internet service providers. Current technology allows Internet users to store their personal calendars, contacts lists, documents, and photographs on third-party servers, which provide convenient access to one’s information from any computer, instead of just on their home computers.

43

The Internet is also redefining what it means to have a conversation, to buy music, or to obtain a book to read. The potentially limitless theory of

Miller

and the increasingly unsatisfying content/non-content distinction the Court drew in

Smith

expose the type of information that Benjamin Franklin would have been able to keep private in his home, unless the government was able to obtain a search warrant. The Patriot Act allows searches and seizures of personal information that the framers might well have equated with the despised general warrant.

But the Supreme Court has not yet declared any limit to the

Miller/Smith

third-party doctrine, and so those decisions are the chief reason why debates over protection of personal information in the hands of a third party have taken place in Congress rather than in the courts.

44

The

Miller

and

Smith

cases, abdicating the Court’s responsibility for protecting Fourth Amendment values, are also one reason why American data privacy laws are so much less protective than those of comparable nations. Once the courts have declared that a practice is not unconstitutional, in our court-centered culture we are likely to assume that the practice is consistent with our values and need not be reexamined. As a result, Congress has also become less inclined to vindicate privacy values. The bottom line, at least so far, is that Congress gets to decide where the floor of protection for records kept by businesses, libraries, schools, hospitals, community organizations, and Internet providers should be set and, in the Patriot Act, Congress decided to lower the floor. The Supreme Court had already left the building.

Reconsidering the “Library Provision”

Enough members of the 2001 Congress had been dubious about whether or not conferring such a broad surveillance power was a good idea that in enacting the Patriot Act, they imposed an expiration date on Section 215. But four years after the Patriot Act, Congress voted to extend this power for another four years before it had any significant information on how the power had been used—beyond Attorney General Gonzales’s testimony about the infrequency of its use. During the 2005 reauthorization deliberations, however, Congress finally showed some interest in exercising oversight and asked the Inspector General of the Justice Department, Glenn Fine, to investigate how this power had been used. Inspector General Fine’s first report on the use of Section 215 was released in March 2007, five and a half years after the provision’s adoption. The report concluded that Section 215 had not been misused because, as Gonzales had said, it simply had not been used much at all. Because of procedural complexities in getting the process started, the FBI had not begun using this new power until May 2004. The Inspector General also found that Ashcroft and Gonzales had spoken truthfully in saying that Section 215 had never been used in a library. It seems the outspoken librarians had an impact even in the secret recesses of the FBI offices. According to the report, on several occasions agents had proposed obtaining a Section 215 court order to review

library records, but their proposals did not survive the FBI’s internal review process. One supervisor explicitly declined a proposal to apply for a library-related order because of the controversy the librarians had ignited. And so, the report said, the FBI got the information it sought “through other investigative means.”

45

But Section 215 is now loaded and ready for action, and only the Inspector General has any means of learning whether the FBI’s self-restraint with respect to libraries will continue.

In light of the fact that the FBI has never used the Section 215 authority in libraries, so far as we know, and that this power does not actually seem to be necessary, creating an exemption for libraries and bookstores seems like an easy way for Congress to make a statement about our commitment to free speech and thought. Library records could still be obtained if agents could show a court that they have a good reason to want to see them, just as Fourth Amendment norms should require. But special treatment of libraries and bookstores should not deflect pressure for more meaningful protections of other types of private information too. The records of social work agencies like Bridge, schools, medical providers, and many others also implicate important privacy issues. Congress would do better to reinstate meaningful privacy protections for all of the information we share with businesses and librarians by adopting a real standard of individualized suspicion and giving the reviewing court something to review.

While business leaders had generally been supportive of the Patriot Act, some became concerned about the problems the new massive security apparatus was creating for themselves and their customers.

46

The mayor of Las Vegas, for example, complained about the FBI gathering information from local businesses concerning close to a million people who had visited Las Vegas during a particular time period, characterizing this prodigious collection of business records as “Kafkaesque”: “The central component to our economy is privacy protection. People are here to have a good time and don’t want to worry about the government knowing their business.”

47

In addition to sensitive customer information, businesses may be required to expose their confidential data and trade secrets. Multinational companies have particular reason to worry because, like Pavlov’s dogs, they are subject to conflicting sets of demands: under United States law they may be required to share confidential customer data with the government; under the more protective data privacy laws of other countries, like the European Union and Canada, they may be prohibited from divulging that same information.

48

And they risk prosecution on charges unrelated to terrorism once the

government is examining their records. Might the government find what it would regard as evidence of tax evasion or price-fixing? And so at the 2005 reauthorization hearings, some business leaders lobbied for greater protection of their customers’ privacy.

49

Perhaps it was to appease this powerful lobby as well as the feisty librarians that the Senate had wanted in 2005 to adopt a new, more rigorous standard for court orders under Section 215. But because the House of Representatives did not concur, in the end, only minor changes were made to the substance of this provision. Nevertheless, Congress showed that it was still concerned about the scope and impact of this authority. Although fourteen of the sixteen originally sunsetting Patriot Act provisions were renewed and made permanent during the 2005 reauthorization hearings, the “library provision” was not made permanent. A new sunset was imposed on Section 215, requiring Congress to revisit these issues in 2009.

When the second round of Patriot Act sunset hearings came around in 2009–2010, the Obama Administration and a Democratic Congress seemed interested in modifying this authority. Both the House and Senate Judiciary Committees approved bills to raise the standard for Section 215 orders. Although the administration supported continuing the “library provision,”

50

in 2009–2010 Obama seemed willing to negotiate about procedural modifications. The proposed amendments never came to a vote on the floor, however. Instead, Congress, with the administration’s support, punted. Congress simply reauthorized the provisions until February and then May 2011.

51

On May 26, 2011, the very day the extended provisions were to expire at midnight, Congress again extended Section 215, without modification, by a Senate vote of 72-23. (The rush was so great that President Obama, who was in Europe, signed the bill remotely by autopen.) Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) had forced a floor vote on whether to provide greater protection for records involving gun sales and banking.

Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), who had sponsored a different unsuccessful amendment to Section 215, dropped a bombshell: “When the American people find out how their government has secretly interpreted the Patriot Act, they will be stunned and they will be angry.”

52

A Justice Department spokesperson declined to explain Wyden’s cryptic reference, insisting that there was no problem because congressional oversight committees and the FISA court were aware of the controversial interpretation in question. Ask the librarians whether that’s good enough.

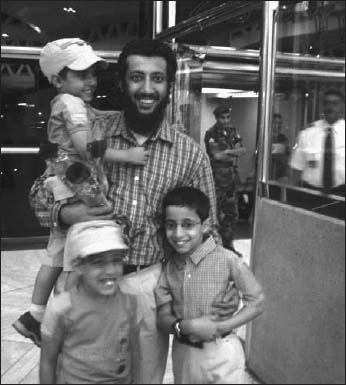

Graduate student Sami al-Hussayen, shown here with his sons, was prosecuted for posting links on a website.

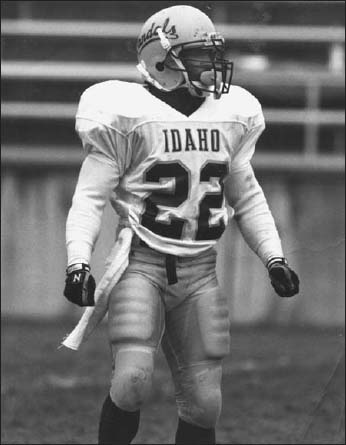

College football player Lavoni T. Kidd, who converted to Islam while at the University of Idaho and changed his name to Abdullah al-Kidd, found himself arrested and detained as a “material witness” but never called to testify even though he was never called to testify at any proceeding.