Tales From Moominvalley (14 page)

Read Tales From Moominvalley Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Animals, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Family, #Classics, #Moomins (Fictitious Characters), #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Dragons; Unicorns & Mythical, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish, #Short Stories

Now he felt a shiver from head to tail and in great excitement saw the boat draw nearer. The hattifatteners did not signal to him in reply - one couldn't even imagine them making such large and everyday gestures - but it was quite clear that they were coming for him. With a faint rustling their boat ploughed into the gravel and lay still.

The hattifatteners turned their round, pale eyes to Moominpappa. He tipped his hat and started to explain. While he spoke the hattifatteners' paws started to wave about in time to his words, and this made Moominpappa perplexed. He suddenly found himself hopelessly tangled up in a long sentence about horizons, verandahs, freedom and drinking tea when one doesn't want any tea. At last he stopped in embarrassment, and the hattifatteners' paws stopped also.

Why don't they say anything? Moominpappa thought nervously. Can't they hear me, or do they think I'm silly?

He offered his paw and made a friendly, interrogatory noise, but the hattifatteners didn't move. Only their eyes slowly changed colour and became yellow as the evening sky.

Moominpappa drew his paw back and made a clumsy bow.

The hattifatteners at once rose and bowed in reply, very solemnly, all three at the same time.

'A pleasure,' Moominpappa said.

He made no other effort to explain things, but clambered aboard and thrust off. The sky was burning yellow, exactly as it had been that other time. The boat started on a slow outward tack.

Never in his life had Moominpappa felt so at ease and pleased with everything. He found it splendid for a change not to have to say anything or explain anything, to himself or to others. He could simply sit looking at the horizon listening to the cluck of the water.

When the coast had disappeared a full moon rose, round and yellow over the sea. Never before had Moominpappa seen such a large and lonely moon. And never before had he grasped that the sea could be as absolute and enormous as he saw it now.

All at once he had a feeling, that the only real and convincing things in existence were the moon and the sea and the boat, with the three silent hattifatteners.

And the horizon, of course - the horizon in the distance where splendid adventures and nameless secrets were waiting for him, now that he was free at last.

He decided to become silent and mysterious, like a hattifattener. People respected one if one didn't talk. They believed that one knew a great many things and led a very exciting life.

Moominpappa looked at the hattifatteners at the helm. He felt like saying something chummy, something to show he understood. But then he let it alone. Anyway, he didn't find any words that - well, that would have sounded right.

What was it the Mymble had said about hattifatteners? Last spring, at dinner one day. That they led a wicked life. And Moominmamma had said: That's just talk: but My became enormously interested and wanted to know what it meant. As far as Moominpappa could remember no one had been really able to describe what people did when they led a wicked life. Probably they behaved wildly and freely in a general way.

Moominmamma had said that she didn't even believe that a wicked life was any fun, but Moominpappa hadn't been quite sure. It's got something to do with electricity, the Mymble had said, cocksurely. And they're able to read people's thoughts, and that's not allowed. Then the talk had turned to other things.

Moominpappa gave the hattifatteners a quick look. They were waving their paws again. Oh, how horrible, he thought. Can it be that they're sitting there reading my thoughts with their paws? And now they're hurt, of course... He tried desperately to smooth out all his thoughts, clear them out of the way, forget all he had ever heard about hattifatteners, but it wasn't easy. At the moment nothing else interested him. If he could only talk to them. It was such a good way to keep one from thinking.

And it was no use to leave the great dangerous thoughts aside and concentrate on the small and friendly sort. Because then the hattifatteners might think that they were mistaken and that he was only an ordinary verandah Moominpappa...

Moominpappa strained his eyes looking out over the sea towards a small black cliff that showed in the moonlight.

He tried to think quite simple thoughts: there's an island in the sea, the moon's directly above it, the moon's

swimming in the water - coal-black, yellow, dark blue. At last he calmed down again, and the hattifatteners stopped their waving.

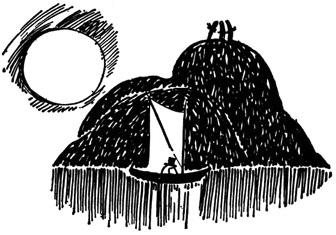

The island was very steep, although small.

Knobbly and dark it rose from the water, not very unlike the head of one of the larger sea-serpents.

'Do we land?' Moominpappa asked.

The hattifatteners didn't reply. They stepped ashore with the painter and made fast in a crevice. Without giving him a glance they started to climb up the shore. He could see them sniffing against the wind, and then bowing and waving in some deep conspiracy that left him outside.

'Never mind me,' Moominpappa exclaimed in a hurt voice and clambered ashore. 'But if I ask you if we're going to land, even if I see that we are, you might still

give me a civil answer. Just a word or two, so I feel I've company.'

But he said this only under his breath, and strictly to himself.

The cliff was steep and slippery. It was an unfriendly island that told everyone quite clearly to keep out. It had no flowers, no moss, nothing - it just thrust itself out of the water with an angry look.

All at once Moominpappa made a very strange and disagreeable discovery. The island was full of red spiders. They were quite small but innumerable, swarming over the black cliff like a live red carpet.

Not one of them was sitting still, everyone was rushing about for all his worth. The whole island seemed to be crawling in the moonlight.

It made Moominpappa feel quite weak.

He lifted his legs, he quickly rescued his tail and shook it thoroughly, he stared about him for a single spot empty of red spiders, but there was none.

'I don't want to tread on you,' Moominpappa mumbled. 'Dear me, why didn't I remain in the boat... They're too many, it's unnatural to be so many of the same kind... all of them exactly alike.'

He looked helplessly for the hattifatteners and caught sight of their silhouettes against the moon, high up on the cliff. One of them had found something. Moominpappa couldn't see what it was.

No difference to him, anyway. He went back to the boat, shaking his paws like a cat. Some of the spiders had crawled on to him, and he thought it very unpleasant.

They soon found the painter also and started to crawl along it in a thin red procession, and from there further along the gunwale.

Moominpappa seated himself as far astern as possible.

This is something one dreams, he thought. And then one awakens with a jerk to tell Moominmamma: 'You can't imagine how horrible, dearest, such a lot of spiders, you never...'

And she awakens too and replies: 'Oh, poor Pappa - that was a dream, there aren't any spiders here...'

The hattifatteners were slowly returning.

Immediately every spider jumped high with fright, turned and ran back ashore along the painter.

The hattifatteners came aboard and pushed off. The boat glided out from the black shadow of the island, into the moonlight.

'Glory be that you're back! Moominpappa cried with great relief. 'As a matter of fact I've never liked spiders that are too small to talk with. Did you find anything interesting?'

The hattifatteners gave him a long moon-yellow look and remained silent.

'I said did you find anything,' Moominpappa repeated, a little red in the snout. 'If it's a secret of course you can keep it to yourselves. But at least tell me there

was

something.'

The hattifatteners were quite still and silent, only looking at him. At this Moominpappa felt his head grow hot and cried:

'Do you like spiders? Do you like them or not? I want to know at once!'

In the long ensuing silence one of the hattifatteners took a step forward and spread its paws. Perhaps it had replied something - or else it was just a whisper from the wind.

'I'm sorry,' Moominpappa said uncertainly, 'I see.' He felt that the hattifattener had explained to him that they had no special attitude to spiders. Or else it had deplored something that could not be helped. Perhaps the sad fact that a hattifattener and a Moominpappa will never be able to tell each other anything. Perhaps it was disappointed in Moominpappa and thought him rather childish. He sighed and gave them a downcast look. Now

he could see what they had found. It was a small scroll of birch-bark, of the sort the sea likes to curl up and throw ashore. Nothing else. You can unroll them like documents: inside they're white and silk-smooth, and as soon as they're released they curl shut again. Exactly like a small fist clasped about a secret. Moominmamma used to keep one around the handle of her tea-kettle.

Probably this scroll contained some important message or other. But Moominpappa wasn't really curious any longer. He was a little cold, and curled up on the floor of the boat for a nap. The hattifatteners never felt any cold, only electricity.

And they never slept.

Moominpappa awoke by dawn. He felt stiff in the back and still rather cold. From under his hatbrim he could see part of the gunwale and a grey triangle of sea falling and rising and falling again. He was feeling a little sick, and not at all like an adventurous Moomin.

One of the hattifatteners was sitting on the nearest thwart, and he observed it surreptitiously. Now its eyes were grey. The paws were very finely cut. They were flexing slowly, like the wings of a sitting moth. Perhaps the hattifattener was talking to its fellows, or just thinking. Its head was round and quite neckless. Most of all he resembles a long white sock, Moominpappa thought. A little frayed at the lower, open end, and as if made of white foam rubber.

Now he was feeling a little sicker still. He remembered his behaviour of last night. And those spiders. It was the first time he had seen a spider frightened.

'Dear, dear,' Moominpappa mumbled. He was about to sit up, but then he caught sight of the birch-bark scroll and stiffened. He pricked his ears under the hat. The scroll lay in the bailer on the floor, slowly rolling with the movement of the boat.

Moominpapppa forgot all about seasickness. His paw cautiously crept out. He gave the hattifatteners a quick look and saw that their eyes as usual were fixed on the horizon. Now he had the scroll, he closed his paw around it, he pulled it towards him. At that moment he felt a slight electric shock, no stronger than from a flashlight battery when you feel it with your tongue. But he hadn't been prepared for it.

He lay still for a long time, calming himself. Then started slowly to unroll the secret document. It turned out to be ordinary white birch-bark. No treasure map. No code letter. Nothing.

Perhaps it was just a kind of visiting card, politely left on every lone island by every hattifattener, to be found by other hattifatteners? Perhaps that little electric shock gave them the same friendly and sociable feeling one gets from a nice letter? Or perhaps they had an invisible writing unknown to ordinary trolls? Moominpappa disappointedly let the birch-bark curl itself back into a scroll again, and looked up.