Tamam Shud (13 page)

Authors: Kerry Greenwood

I have two reasons for disagreeing with the ghouls â a practical reason and an emotional reason. In practical terms, Teresa Powell was a nurse. She may have been surprised by an unplanned pregnancy but she was working at the Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney and nurses knew things that many other women in 1948 didn't, one of them being a safe place to get an abortion. If Teresa Powell didn't want to keep that baby, she didn't have to do so, which argues that she knew and loved the father

and was sure that he would take care of both of them.

And on the emotional level, it seems unlikely that she was relying on Somerton Man, given that she already had a man to marry, as soon as his divorce came through. She may well have been in Adelaide to remove herself from temptation and make sure that Mr Johnson divorced his previous wife without any complicating factors. Under the old

Matrimonial Causes Act

, anyone who might be involved with a divorcee was obliged to pass the interval between the

decrees nisi

and absolute, as AP Herbert says, in another country. Or in a nunnery. Any suggestion of collusion and the divorce was off. I do not know whether Mr Johnson was suing for divorce or being sued and at this late date I do not propose to pry. But it is a matter of public record, and as I have referred to earlier, that he married Miss Powell in 1950 as soon as he was free to marry, and they stayed married until he died in 1995 and she died in 2007.

Gerald Feltus, who as we know interviewed Teresa for his book on the Tamam Shud case, was sure that she knew the identity of Somerton Man but that doesn't necessarily prove that he was her lover. While it is true that Teresa Powell gave a

Rubaiyat

to a drinking companion in Sydney, I am recapping here, I am not convinced that this links her to Somerton Man. After all, there is no naughty little verse in the front of Somerton Man's first edition and no inscription from Jestyn, just her phone number

in the back of the book, scribbled there perhaps because he had nothing else to write on. (There is no notebook, either in his pockets or his luggage). I do believe he came to Somerton Beach to see Teresa but I don't think he was her lover. He left his suitcase at Central Station. He wasn't expecting to stay. If someone comes up with some DNA from the hair caught in that plaster cast, I'd bet a good dinner at my favourite restaurant Attica that the DNA tests would prove that Somerton Man was related to Teresa Powell but not the father of her son.

Like my father, I have always been a cautious gambler and, like him, I never bet my bus money, which means I am tolerably certain about this bet. But if I am wrong, I get another dinner at Attica, so there is, as my nephew says, no actual downside. In any case, there is no way of proving or disproving this theory at present. Professor Abbott's request for the exhumation of Somerton Man in October 2011 was refused by the Attorney-General, who said that there was no public interest (this phrase has a precise legal meaning) in such an exhumation which âwent beyond curiosity'. Besides, the chance that Somerton Man and Teresa's son are not in some way related is estimated at one in 20 million â although that's the sort of chance that wins lotteries, so it does happen.

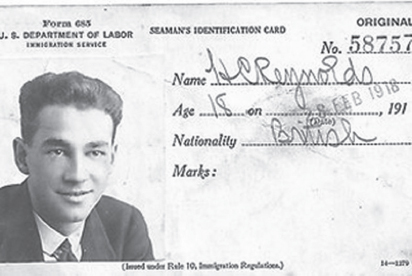

Meanwhile, as well as analysing the ears of Somerton Man, Professor Henneberg also examined the photograph of a man called HC Reynolds and found Reynolds's ears and other facial markers to be the same as the man found dead on Somerton Beach. Henneberg goes so far as to say that âTogether with the similarity of the ear characteristics, this mole, in a forensic case, would allow me to make a rare statement positively identifying the Somerton Man'. So who is HC Reynolds? The photo in question comes from an old ID card, issued in 1918 by the American authorities and later given to Gerald Feltus by a person he describes only as âRuth Collins, an Adelaide woman'. On the ID card HC Reynolds is identified as

British and eighteen years old at the time â the right age for Somerton Man, who was estimated in 1948 to be in his late forties or early fifties.

The photograph from HC Reynolds identity card issued in 1918 was examined by a Professor Henneberg, who found that the man's ears and other facial markers appeared to be the same as those of Somerton Man.

Courtesy Maciej Henneberg.

ID cards were issued to sailors who wanted to go ashore in American ports and didn't have passports. Passports are a relatively recent invention and not every sailor had one, especially in that era. Extensive searches through various English and Australian archives have failed to find anyone by the name of HC Reynolds who was born, as he must have been, in 1900. One researcher, who is convinced that the ID card was issued to a shipwreck survivor, is still checking survivor lists. It is possible that the researchers haven't consulted the right database yet but it is also possible that Reynolds wasn't his real name. Identity is not an absolute. One of Australia's more famous heroes was an English deserter who was actually called Kirkpatrick but enlisted in the army under the name of Simpson. (He and his donkey later attracted some notice.)

In 1900, birth registrations were patchy. Any genealogical researcher â and there is an army of them out there, combing through all the records in search of their great grandfathers â can tell you that sometimes you need to check baptismal registers and family records, not only to pin down the date of a birth but to establish whether it happened at all.

Adoptions in the old days were frequently informal. The big difference between any country, then and now,

is that there was a surplus of children then. Before reliable contraception, many women had, perforce, far more children than they could feed, so some of those children went to orphanages and children's homes and sisters and aunts. Children born out of wedlock were often not even registered, if they were born at home, and some of them were quietly done away with. The writer and historian Lucy Sussex reports that her grandmother found a tiny skeleton buried in a vicarage garden and buried it again, saying with compassion that it must have been âa servant's child' and that it was best to âlet sleeping dogs lie'. In short, even if our HC Reynolds is definitely not on the official record, at least under that name, there might be many reasons for it.

Somerton Man continues to attract speculation. There is an article in the 1994

Criminal Law Journal

by that excellent judge and historian, John Harber Phillips, who gives a nice little summary of the case and decides that Somerton Man died of digitalis poisoning, despite the previous forensic objections to this idea. My sister believes that the story of Somerton Man is a love story and she might be right. Others have suggested that the piece of paper in his fob pocket saying âTamam Shud' is a love token rather than a code. We are also told that Stephen King's novel

The Colorado Kid

is based on the case of Somerton

Man. It is the story of a man found dead on a beach with no identification and the newspaper reporters who try to solve the mystery. I do not usually admire King but I am an avid watcher of

Haven

, the TV series derived from

The Colorado Kid

, and the book itself is an interesting meditation on the nature of apprenticeship, experience and learning.

However, it is not about Somerton Man, according to Stephen King himself, who says in his introduction to the 2005 edition that the book was, in fact, inspired by the case of a woman found dead on the shore in Maine. King reports that a fan sent him a clipping, which he has since lost, about a young woman with a bright red purse, who was seen walking on the beach one day, found dead on it the next and remained unidentified for a long time. King loves the strangeness of Maine and in his introduction he says, âIn this case I'm not really interested in the solution, but in the mystery'.

The same could be said of all of us who have puzzled over the mystery of Somerton Man. âWanting,' says King âis better than knowing.' And he may be right.

In her 2010 article âThe Somerton Man: an unsolved history', Ruth Balint, a senior lecturer in the School of History and Philosophy at the University of New South Wales, goes to considerable lengths to understand her subject. For instance, she is conducted around Adelaide by Gerry Feltus, the detective who published his own

book on Somerton Man in the same year, visiting various places that are important to Somerton Man's story, like the station and Somerton Beach. There are theories that point to the Somerton Man being a displaced person, which do make sense considering the time and place.

After the ruin of Europe, thousands of people flooded into the less destroyed parts of the world. Nazis tended to go to Argentina, for example. On the other hand, my old and distinguished friend Dennis Pryor came to Australia from England as a ten-pound tourist and never wanted his money back. Australia was seen as a fresh start, innocent of the dreadful animosities of old Europe.

Balint sees Somerton Man as a wandering refugee, clad in anonymous second-hand clothes, rather than attributing his lack of labels to deliberate action. She points to a conversation the police had with âMr Moss Keipitz, an Egyptian, employed in Adelaide', who told the police investigation that Keane, the name on Somerton Man's tie, could have been an Anglicisation of Keanic, which is a Czechoslovakian, Yugoslav or Baltic name. (My mother did think he looked Baltic.) However, Balint adds that since Somerton Man's fingerprints were only sent to the United States and to other countries in the British Commonwealth, not to Eastern Bloc countries, there is no way to prove or disprove her theory. She observes that there are an infinite number of potential endings to the mystery, which is interesting and also true but not helpful.

One of my favourite theories is that Somerton Man was a time traveller, related to Teresa Powell because he was her great-great-grandson come back from the future, where clearly it is colder than here, hence the heavy garments. According to this theory, Somerton Man was waiting on the beach for the Mothership but he was killed by an acute reaction to some local allergen or a death ray from his enemies before he could be picked up. As one who read their first speculative fiction story at eight â a time travel story by Ray Bradbury called

The Sound of Thunder

, which scared the hell out of me â I love the idea. Both of the unidentified dead men found on Somerton Beach were inappropriately dressed for the weather in their current location but were they, perhaps, appropriately dressed for their ultimate destination â a colder future earth or a chilly day on Mars? The only trouble with this hypothesis is that time travel really is impossible. Much as I like the idea.

A similar degree of suspension of disbelief is required by the idea that Somerton Man was an alien/human hybrid. As a matter of fact, this theory requires that disbelief be not so much suspended as hung out of the window by its heels. I suspect that the theorists watched

The X Files

and thought it was fact. Still, it's an attractive hypothesis, based on the fact, uncovered by Professor Abbott, that Somerton Man had some unusual genetic features â those odd teeth and strange ears. However, strange ears do not a Vulcan make, nor a fairy, werewolf, elf or supernatural personage of any sort. Despite what you may have read in

Twilight

. Despite the novels of Charlaine Harris. No, really. Srsly.

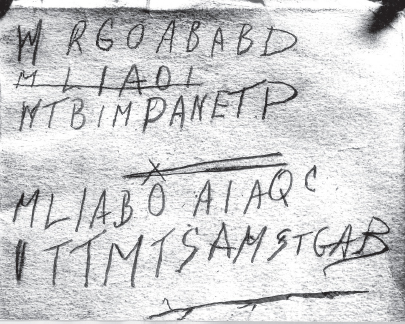

The mysterious code. Many have tried to break it, no one has succeeded â yet.

In the end, after all the theorising, Somerton Man remains an ambiguous figure. Was he on our side or on their side? Was he a good guy or a bad guy? Where did he come from, what was he doing there, how did he die? Only a novelist, I suggest, could possibly provide a solution, because every hypothesis put forward so far has had to ignore at least one of the facts, like the Marx brothers

packing a suitcase by cutting off the bits which don't fit. And my own solution is only a story, or rather, several stories; and I am a storyteller who draws inferences from many sources. We cannot really hope to solve this mystery now, even if we dig up poor Somerton Man and trace his blood relatives by their DNA or the shape of their ears.