Tango (9 page)

Authors: Mike Gonzalez

In Paris, the tango was at the heart of an exploration of sensuality and eroticism, albeit restrained by middle-class mores. But its stars were as sensual as the two dominant figures of the cabarets â

Mistinguett and Josephine Baker. Cabaret was a spectacle, a theatrical drama that on a smaller scale could be re-enacted on the dance floor with a greater or lesser degree of physical contact and erotic simulation. In a sense, as it developed, tango moved between the

rufianesco

â the pimp's enactment of sexual pleasure and the battle between men for the attention of the prostitute â and

romántico

, in which those initial gyrations had been stylized and dramatized.

16

In these early years of the twentieth century, as it travelled the world, tango moved between these two expressions.

In the French capital, the memory of the Apache dance conserved that feeling of the underworld and a struggle for power between men and women. Among the early pupils there was the young Rudolph Valentino, whose tango in the

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

not only launched him into the realms of superstardom but also created an iconic image of the dance itself. As described by Marta Savigliano, Valentino's version is closer to the Apache dance or the

valse chaloupé

that Mistinguett presented before her public. The scene is âthe famous Boca quarter of Buenos Aires'. Valentino, dressed as a

gaucho

, complete with riding crop, watches Beatrice DomÃnguez dancing with a man she clearly does not like. He pushes him away and Valentino and DomÃnguez enter the frame.

After some individual gyrations, their hands join and they move around the dance floor performing smooth glides, controlled dips and slow sensuous swayings. Finally they embrace too closely and she breaks into contortions attempting to avoid a kiss that he insistently seeks. Unable to satisfy his desire, Valentino pushes her away with violence. She lands on the floor and drags herself to his feet in an ambivalent gesture of hatred and rapture. In the end he resorts to his secret weapon, his

boleadoras

, . . . and lassoes her.

It is the perfect machista ritual.

The journey to London, and from there to New York, softened and modified the element of erotic confrontation. The dance craze in Britain was tied to a notion of âsocial dancing', with its emphasis on etiquette, refined social conduct and a properly prepared environment â as set out in Gladys Beattie Crozier's manual

The Tango and How to Do It

(1913). By 1913, the instruction manuals were proliferating and exhibition dancing on both sides of the Atlantic became a profitable pursuit. And the influence of tango was not limited to the dance itself. Fashion acknowledged the demand for freer movement for women, boned corsets were replaced by more flexible basques, and lightweight fabrics were introduced which both permitted ease of movement and emphasized the sensuality and fluidity of the dancer. Orange, the colour of tango, became dominant and new dishes claimed their origins in tango.

17

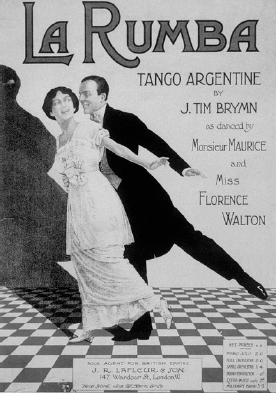

âLa Rumba' poster. |

|

The dance that had celebrated its origins in the sexual underworld and the primitive rural world, exemplified in dress and gesture, was giving way to the romantic version on the one hand, and on the other to dance as a sport. The sensual movements of the original became athletic actions instead, and the embrace gradually returned to the formal distance between the partners that had been closed in the body contact that had so taken aback the Scottish writer Robert Cunninghame Grahame.

As they walked through the passages, men pressed close up to women and murmured in their ears, telling them anecdotes that made them flush and giggle, as they protested in an unprotesting style. Those were the days of the first advent of the Tango Argentino, the dance that has since circled the whole world, as it were, in a movement of the hips. Ladies pronounced it charming as they half closed their eyes and let a little shiver run across their lips. Men said that it was the only dance worth dancing. It was so Spanish, so unconventional, and combined all the aesthetic movements of the figures on an Etruscan vase with the strange grace of Hungarian gypsies . . . it was, one may say, so . . . as you may say . . . you know.

18

It was under this conservative Anglo-Saxon influence that tango became a social dance, and increasingly a kind of sport where athleticism prevailed over sensual expression. There were international competitions, and â after a struggle â the dance was redefined. It was now no longer âLatin', with all the exotic implications of the word, but âmodern', incorporated into the world of

contemporary ballroom dancing, with its rapidly accumulating rules and regulations. The interweaving of limbs should now occur only symbolically and at a distance â as the dance manuals of Vernon and Irene Castle made very clear.

The music was changing too, in response to the twin impact of tango's globalization and the expansion of its clientele into the bourgeois centres of the world's great cities. The fast

milonga

had given way to the slower more dramatic expression encouraged by the bandoneon. In Paris, the

âOrquesta tÃpica'

dressed in national dress to play for the dancers. By 1913, however, the ensembles were growing, adding extra bandoneons and strings, and their dress was changing too. Dinner jackets reflected the tango's entry into the elegant world of the French bourgeoisie, but they in turn responded to the exoticism and excitement of the dance. At the same time, the dance was re-choreographed. While Stravinsky's

The Rite of Spring

still resonated with a self-conscious primitivism, Grossmith and Dare's hit 1916 musical

The Sunshine Girl

featured a tango considerably less daring than its original.

19

Paris tango in 1913.

The first generation of tango musicians, dancers and singers were often workers who played at night in the brothels and cafés. In Paris, they changed their mode of dress and became professionals. Few of these early musicians had musical training â Rosendo Mendizábal was an important exception â but they began to commit their songs to paper as the new century opened, humming or whistling their tunes for others to set them down. Eduardo Arolas, a renowned bandoneon player, was among the first tango lyricists, as improvised words gave way to written lyrics. His tango âUna noche de garufa' (1909), with words by Gabriel Clausi, vies for a place as the first tango with lyrics.

En esta noche de garufa yo me quiero divertir

con los amigos

de bohemia en el viejo Armenonville

.

La vida es corta y se

pianta muy pronto

,

en esta noche hay que vivir

.

En las nostálgicas veladas

vuelve el tiempo del ayer

con este tango que nos lleva

como un sueño a su compás

.

Viejos recuerdos, paicas papusas

,

dulce momento del ayer

.

Cómo me emocionan tus notas

en esta velada porteña

,

deja que la música embriague

para hacer, del tango una fiesta

.

On this night of pleasure I will take it where I can / With my Bohemian friends in the old Armenonville. / Life is short and ends all too soon / So this night is for living. / In those nostalgic parties / Yesterday returns / With the tango that carries us / into a dream

with its rhythm / Old memories, beautiful women we loved / Sweet moments in the past. / The music moves me so in this Buenos Aires night / Let the music intoxicate you / And let the tango / turn the night into a celebration

.

(âUna noche de garufa'

,

A night of pleasure â Eduardo Arolas, 1909)

Arolas went to Paris in 1919, and died there in mysterious circumstances in 1924. He was 32 years old. His story was repeated among the young men and women who pursued the dream of Paris. Nearly all the musicians and performers emerged from urban poverty in Argentina; most died in very similar circumstances. In 1913, it was reported that over 100 Argentine, musicians, singers and dancers flocked to Paris; few made a living.

The tango craze which they hoped to benefit from had two very different expressions. On stage and in revue, tango retained its powerful exotic charge and its sexuality. But in the dance salons, the tango followed new rules established by dance masters like the Castles in the

U

.

S

. or M. André de Fouquières in Paris.

20

The original choreography had been stylized into glamorous, almost balletic, postures (extended arms, stretched torsos and necks, light feet) and rough apache-like figures (deep dips, backward bends, dizzying sways) with matching walks in between . . . The basic continental tango was glamorised on the stages and tamed in the ballrooms . . . the music was especially composed so as to be exotically languid and retained only some of its rhythm.

21

For those Argentines who found themselves in Europe or the United States, there was little alternative but to act out Western fantasies of Argentine life. As Buenos Aires was rapidly becoming one of the world's largest cities, its urban culture was being represented in

gaucho

costume and rural backdrops. In the

U

.

S

.,

tango had also changed in deference to the sensibilities of the middle classes. The Castles emphasized elegance and pattern in the dance, and held the partners in a safely distant embrace. When the wealthy Mrs Stuyvesant wanted a tango for her salon, but baulked at the sensuality of it, the Castles conceived the âInnovation' whose distinguishing feature was that the partners did not touch! The Castles went to some lengths to tame and colonize, describing the tango in their influential

Modern Dance

of 1914 thus:

The much-misunderstood Tango becomes an evolution of the eighteenth century Minuet . . . when the Tango degenerates into an acrobatic display or into salacious sensation it is the fault of the dancers and not of the dance. The Castle tango is courtly and artistic.

22

The tango musicians and dancers who were seeking their fortune in Europe and the United States would have had considerable difficulty in accepting that. Indeed, despite the fact that the Victor label in the

U

.

S

. and Odeon in Europe were successfully recording some of these artists, in the United States the music was attenuated and adapted to the local morality, and the more popular lyrics were those written by local writers who often translated exoticism into the absurdity of the novelty song.

When the great big Dip Dip Dip Dipper

Did the Tango in the sky

He told them all the merry news

As he went rolling by

.

Then he called on Jupiter Pluvius

For his orchestra to play

And the Price of admission to this wonderful dance

,

Was a tiny silv'ry ray

. . .

23