Team of Rivals (24 page)

Authors: Doris Kearns Goodwin

Most of the Free-Soilers were former Whigs who would not vote with the Democrats. They favored Giddings. Two independents, meanwhile, vacillated: Dr. Norton Townshend, once a Democrat, who had been a member of the Liberty Party; and John F. Morse, formerly a “conscience Whig.” The decisions of these two men would prove pivotal. Working behind the scenes, Chase drafted a deal with Samuel Medary, the boss of the Democratic Party in Ohio. If Chase delivered Townshend and Morse to the Democrats, Medary would see to it that Chase became the new U.S. senator. In addition, the Democrats would vote to repeal the Black Laws, a condition Morse insisted upon before he would agree to the deal. In return, the Democrats would have the House speakership and control of the extensive patronage that office enjoyed. For Medary, control of the state was far more important than naming a senator.

Chase worked ceaselessly to deliver Townshend and Morse to the Democrats. While Giddings remained in Washington, Chase journeyed to Columbus and took a room at the Neil House close to the state Capitol so he could attend Free Soil caucuses at night and negotiate with individual Democrats during the day. He planted articles in key newspapers, praising not only himself but Townshend and Morse. He lent money to more than one paper, and when the needs of the Free Soil weekly, the Columbus

Daily Standard,

exceeded his means, he reassured its editor: “After the Senatorial Election, whether the choice falls on me or another, I can act more efficiently, and you may rely on me.” He advanced money to the

Standard

and later agreed to a loan but refused to take a mortgage on the newspaper as security because he did not want his name publicly connected, “which could not be avoided in case of a mortgage to myself.”

Knowing that Morse was introducing a bill to establish separate schools for blacks, Chase enlisted the editor of the

Standard

to help get it passed. “It is really important,” he urged, “and if it can be got through with the help of democratic votes, will do a great deal of good to the cause generally & our friend Morse especially.” Certainly, it would do a great deal of good for the career of Salmon Chase, who sanctimoniously told Morse that the only consideration in determining the next senator should be ability to best advance the cause: “Every thing, but sacrifice of principle, for the Cause, and nothing for men except as instruments of the Cause.” Advancement of self and advancement of the cause were intertwined in Chase’s mind. In Chase’s mind, both were served when Morse and Townshend voted with the Democrats to organize the legislature and the victorious Medary swung his new Democratic majority to Chase for senator.

The unusual circumstances of Chase’s election provoked negative comment in the press. “Every act of his was subsidiary to his own ambition,” charged the

Ohio State Journal:

“He talked of the interests of Free Soil, he

meant

His Own.” This judgment by a hostile paper was perhaps unduly harsh, for the deal with the Democrats did indeed end up promoting the Free Soil cause. As Medary had promised, the Democrats voted to repeal the hated Black Laws. And when Chase reached the Senate, he would become a stalwart leader in the antislavery cause.

Nonetheless, fallout from Chase’s Senate election eventually found its way into the widely circulated pages of Horace Greeley’s

New York Tribune.

Editorializing on the machinations involved, Greeley declared that he did “not see how men who desire to maintain a decent reputation can countenance or profit by it.” Indeed, the suspicions and mistrust engendered by the peculiar circumstances of the Senate election would never be wholly erased. “It lost to him at once and forever the confidence of every Whig of middle age in Ohio,” a fellow politician observed. “Its shadow never wholly dispelled, always fell upon him, and hovered near and darkened his pathway at the critical places in his political after life.” The Whigs, and their later counterparts, the Republicans, would deny Chase the united support of the Ohio delegation so vital to his hopes for the presidential nomination in 1860. And Chase, for his part, would never forgive them.

Showing little intuitive sense of how others might view his maneuvering, Chase failed to appreciate that with each party shift, he betrayed old associates and made lifelong enemies. Certainly, his willingness to sever bonds and forge new alliances, though at times courageous and visionary, was out of step with the political custom of the times.

Though troubled by the criticism attending his election, Chase was thrilled with his victory. So was Charles Sumner, who would join Chase two years later in the Senate by way of a similar alliance between Free-Soilers and independent Democrats in Massachusetts. “I can hardly believe it,” Sumner wrote. “It does seem to me that this is ‘the beginning of the end.’ Your election must influence all the Great West. Still more your presence in the Senate will give an unprecedented impulse to the discussion of our cause.”

When Chase took his seat in the handsome Senate chamber in March 1849, nearly twenty years had elapsed since his early days as a poor teacher living on the margins of the city’s social whirl. Now, as a renowned political organizer, prominent lawyer, and fabled antislavery crusader, Chase could claim a place in the first tier of Washington society. William Wirt would have been proud. For a brief moment, Chase’s relentless need “to be first wherever I may be” was sated.

As the 1840s drew to a close, William Henry Seward and Salmon P. Chase had moved toward the summit of political power in the United States Senate. Edward Bates, though spending most of his days at his country home with his ever-growing family, had become a widely respected national figure, considered a top prospect for a variety of high political posts. Abraham Lincoln, by contrast, was practicing law, regaling his fellow lawyers on the circuit with an endless stream of anecdotes, and reflecting with silent absorption on the great issues of the day.

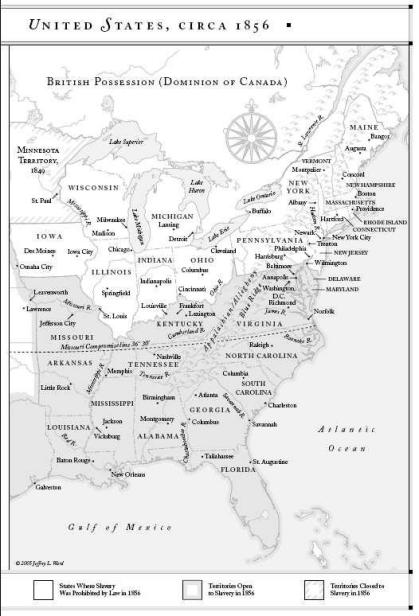

P

OLITICAL

M

AP OF THE

U

NITED

S

TATES, CIRCA 1856

THE TURBULENT FIFTIES

T

HE

A

MERICA OF 1850

was a largely rural nation of about 23 million people in which politics and public issues—at every level of government—were of consuming interest. Citizen participation in public life far exceeded that of later years. Nearly three fourths of those eligible to vote participated in the two presidential elections of the decade.

The principal weapon of political combatants was the speech. A gift for oratory was the key to success in politics. Even as a child, Lincoln had honed his skills by addressing his companions from a tree stump. Speeches on important occasions were exhaustively researched and closely reasoned, often lasting three or four hours. There was demagoguery, of course, but there were also metaphors and references to literature and classical history and occasionally, as with some of Lincoln’s speeches, a lasting literary glory.

The issues and declamations of politics were carried to the people by newspapers—the media of the time. The great majority of papers were highly partisan. Editors and publishers, as the careers of Thurlow Weed and Horace Greeley illustrate, were often powerful political figures. Newspapers in the nineteenth century, author Charles Ingersoll observed, “were the daily fare of nearly every meal in almost every family; so cheap and common, that, like air and water, its uses are undervalued.”

“Look into the morning trains,” Ralph Waldo Emerson marveled, which “carry the business men into the city to their shops, counting-rooms, workyards and warehouses.” Into every car the newsboy “unfolds his magical sheets,—twopence a head his bread of knowledge costs—and instantly the entire rectangular assembly, fresh from their breakfast, are bending as one man to their second breakfast.” A European tourist was amazed at the central role newspapers played in the life of the new nation. “You meet newspaper readers everywhere; and in the evening the whole city knows what lay twenty-four hours ago on newswriters’ desks…. The few who cannot read can hear news discussed or read aloud in ale-and-oyster houses.”

Seventeen years before the decade had begun, President Andrew Jackson had prophesied: “The nullifiers in the south intend to blow up a storm on the slave question…be assured these men would do any act to destroy this union and form a southern confederacy bounded, north, by the Potomac river.”

And now the storm had come.

The slavery issue had been a source of division between North and South from the beginning of the nation. That difference was embodied in the Constitution itself, which provided that a slave would be counted as three fifths of a person for purposes of congressional representation and which imposed an obligation to surrender fugitive slaves to their lawful masters. Although slavery was not named in the Constitution, it was, as antislavery Congressman John Quincy Adams said, “written in the bond,” which meant that he, like everyone else, must “faithfully perform its obligations.”

The constitutional compromise that protected slavery in states where it already existed did not apply to newly acquired territories. Thus, every expansion of the nation reignited the divisive issue. The Missouri Compromise had provided a temporary solution for nearly three decades, but when Congress was called upon to decide the fate of the new territories acquired in the Mexican War, the stage was set for the renewal of the national debate. “If by your legislation you seek to drive us from the territories of California and New Mexico, purchased by the common blood and treasure of the whole people,” Robert Toombs of Georgia warned,

“I am for disunion.”

Mississippi called for a convention of Southern states to meet in Nashville for the defense of Southern rights.

The issue of slavery could no longer be put aside. It would dominate the debates in Congress. As Thomas Hart Benton once colorfully observed: “We read in Holy Writ, that a certain people were cursed by the plague of frogs, and that the plague was everywhere! You could not look upon the table but there were frogs, you could not sit down at the banquet but there were frogs, you could not go to the bridal couch and lift the sheets but there were frogs!” A similar affliction infested national discourse as every other topic was subsumed by slavery. “We can see nothing, touch nothing, have no measures proposed, without having this pestilence thrust before us. Here it is, this black question, forever on the table, on the nuptial couch, everywhere!”

Of course, slavery was not the only issue that divided the sections. The South opposed protective tariffs designed to foster Northern manufacturing and fought against using the national resources for internal improvements in Northern transportation. But issues like these, however hard fought, were subject to political accommodation. Slavery was not. “We must concern ourselves with what is, and slavery exists,” said John Randolph of Virginia early in the century. Slavery “is to us a question of life and death.” By the 1850s, Randolph’s observation had come to fruition. The “peculiar institution” now permeated every aspect of Southern society—economically, politically, and socially. For a minority in the North, on the other hand, slavery represented a profoundly disturbing moral issue. For many more Northerners, the expansion of slavery into the territories threatened the triumph of the free labor movement. Events of the 1850s would put these “antagonistical elements” on a collision course.

“It is a great mistake,” warned John Calhoun in 1850, “to suppose that disunion can be effected by a single blow. The cords which bind these States together in one common Union are far too numerous and powerful for that. Disunion must be the work of time. It is only through a long process…that the cords can be snapped until the whole fabric falls asunder. Already the agitation of the slavery question has snapped some of the most important.” If these common cords continue to rupture, he predicted, “nothing will be left to hold the States together except force.”

The spiritual cords of union—the great religious denominations—had already been fractured along sectional lines. The national political parties, the political cords of union, would be next, splintered in the struggle between those who wished to extend slavery and those who resisted its expansion. Early in the decade the national Whig Party, hopelessly divided on slavery, would begin to diminish and then disappear as a national force. The national Democratic Party, beset by defections from Free Soil Democrats, would steadily lose ground, fragmenting beyond repair by the end of the decade.

The ties that bound the Union were not simply institutions but a less tangible sense of nationhood—shared pride in the achievements of the reolutionary generation, a sense of mutual interests and common aspirations for the future. The chronicle of the 1850s is, at bottom, a narrative of the increasing strain placed upon these cords, their gradual fraying, and their final rupture. Abraham Lincoln would correctly prophesy that a house divided against itself could not stand. By the end of the decade, as Calhoun had warned, only force would be left to sustain the Union.

Was this outcome inevitable? It is not a question that can be answered in the abstract. We must begin with the historical realities and ask if the same actors with the same convictions, emotions, and passions could have behaved differently. Possibly, but all we can know for certain is that they felt what they felt, believed as they believed, and did as they would do. And so they moved the country inexorably toward Civil War.

A

S THE 31ST

C

ONGRESS OPENED,

the rancorous discord boiled to the surface. All eyes turned to the seventy-three-year-old Henry Clay, who, Lincoln later said, was “regarded by all, as

the

man for a crisis.” Henry Clay had saved the Union once before. Now, thirty years after the Missouri Compromise, the Congress and nation looked to him once again. Already Clay suffered from the tuberculosis that would take his life two years later. He could not even manage the stairs leading up to the Senate chamber. Nonetheless, when he took the floor to introduce the cluster of resolutions that would become known as the Compromise of 1850, he mustered, the

New York Tribune

marveled, “the spirit and the fire of youth.”

He began by admitting he had never been “so anxious” facing his colleagues, for he believed the country stood “at the edge of the precipice.” He beseeched his colleagues to halt “before the fearful and disastrous leap is taken in the yawning abyss below, which will inevitably lead to certain and irretrievable destruction.” He prophesied that dissolution would bring a war “so furious, so bloody, so implacable and so exterminating” that it would be marked forever in the pages of history. To avoid catastrophe, a compromise must be reached.

His first resolution called for admitting the state of California immediately, leaving the decision regarding the status of slavery within its borders to California’s new state legislature. As it was widely known that a majority of Californians wished to prohibit slavery entirely, this resolution favored the North. He then proposed dividing the remainder of the Mexican accession into two territories, New Mexico and Utah, with no restrictions on slavery—a provision that favored the South. He called for an end to the slave trade within the boundaries of the national capital, but called on Congress to strengthen the old Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 to facilitate the recapture of runaway slaves. Fugitives would be denied a jury trial, commissioners would adjudicate claims, and federal marshals would be empowered to draft citizens to hunt down escapees.

Clay recognized that the compromise resolutions demanded far greater concessions from the North than he had asked from the slave states, but he appealed to the North to sustain the Union. Northern objections to slavery were based on ideology and sentiment, rather than on the Southern concerns with property, social intercourse, habit, safety, and life itself. The North had nothing tangible to lose. Finally, he implored God that “if the direful and sad event of the dissolution of the Union shall happen, I may not survive to behold the sad and heart-rending spectacle.” This prayer was answered. He died two years later, nearly a decade before the Civil War began.

Frances Seward was in the overcrowded gallery on February 5, 1850, when Henry Clay rose from his desk to speak. She had come to Washington to help her husband get settled in a spacious three-story brick house on the north side of F Street. “He

is

a charming orator,” Frances confessed to her sister. “I have never heard but one more impressive speaker—and that is

our

Henry (don’t say this to anybody).” But Clay was mistaken, she claimed, if he believed the wound between North and South could be sutured by his persuasive charm. Though he might make “doughfaces out of half the Congress,” his arguments had not convinced her. Most upsetting was Clay’s claim that “Northern men were only activated by policy and party spirits. Now if Henry Clay has lived to be 70 years old and still thinks slavery is opposed only from such motives I can only say he knows much less of human nature than I supposed.”

Four weeks later, the galleries were once again filled to hear South Carolina’s John Calhoun speak. Although unsteady in his walk and enveloped in flannels to ward off the chill of pneumonia that had plagued him all winter, the sixty-seven-year-old arch defender of states’ rights appeared in the Senate with the text of the speech he intended to deliver. He rose with great difficulty from his chair and then, recognizing that he was too weak to speak, handed his remarks to his friend Senator James Mason of Virginia to read.

The speech was an uncompromising diatribe against the North. Calhoun warned that secession was the sole option unless the North conceded the Southern right to bring slavery into every section of the new territories, stopped agitating the slave question, and consented to a constitutional provision restoring the balance of power between the two regions. Making much the same argument he had utilized in the early debates surrounding the Wilmot Proviso, he warned that additional free states would tilt the power in the Senate, as well as in the House of Representatives, and destroy “the equilibrium between the two sections in the Government, as it stood when the constitution was ratified.” This final address to the Senate concluded, Calhoun retired to his boardinghouse, where he would die before the month was out.

Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, the third of the “great triumvirate”(as Clay, Calhoun, and Webster were called), was scheduled to speak on the 7th of March. The Senate chamber was “crammed” with more men and women, a Washington newspaper reported, than on any previous occasion. Anticipation soared with the rumor that Webster had decided, against the fervent hopes of his overwhelmingly antislavery constituents, to support Clay’s Southern-leaning compromise. Frances Seward was watching when the senator rose.

“I wish to speak to-day, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a northern man, but as an American,” Webster began. “I speak to-day for the preservation of the Union. ‘Hear me for my cause.’” He proceeded to stun many in the North by castigating abolitionists, vowing never to support the Wilmot Proviso, and coming out in favor of every one of Clay’s resolutions—including the provision to strengthen the hateful Fugitive Slave Law. Many in New England found Webster’s new stand particularly abhorrent. “Mr Webster has deliberately taken out his name from all the files of honour,” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote. “He has undone all that he spent his years in doing.”

Frances found the speech greatly disappointing. The word

“compromise,”

she told her sister, “is becoming hateful to me.” Acknowledging that Webster was “a forcible speaker,” particularly when he extolled the Union, she found him “much less eloquent than Henry Clay because his heart is decidedly colder—people must have feeling themselves to touch others.” Despite such criticisms, the speech won nationwide approval from moderates who desperately wanted a peaceful settlement of the situation. A few antislavery Whigs expressed a fear that Seward might hesitate when the time came to deliver his own speech, scheduled three days later. “How little they know his nature,” Frances wrote. “Every concession of Mr. Webster to Southern principles only makes Henry advocate more strongly the cause which he thinks just.”